Review by Tiziano Thomas Dossena

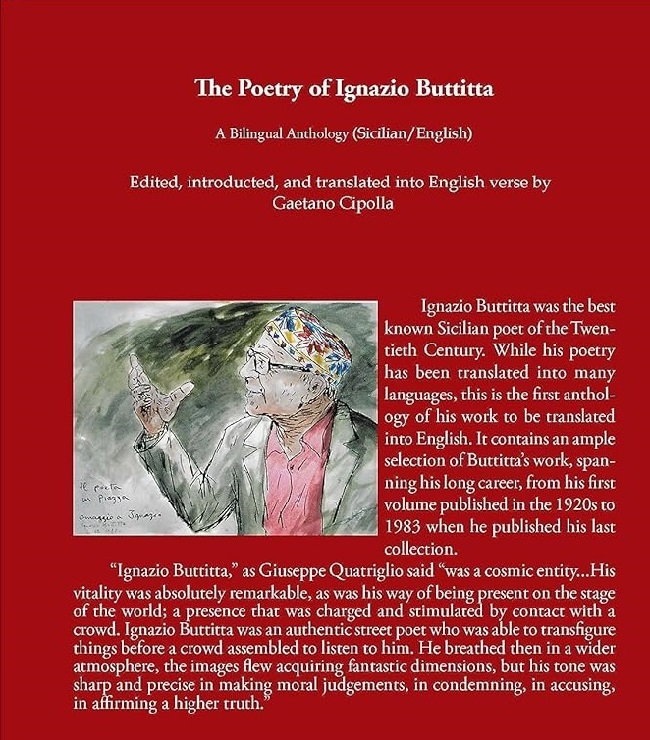

Ignazio Buttitta was the best-known Sicilian poet of the Twentieth Century. While his poetry has been translated into many languages, “The Poetry of Ignazio Buttitta,” edited, introduced, and translated by Gaetano Cipolla, is the first anthology of his work to be translated into English verse. The thirty poems in Sicilian offer an ample selection of his work, spanning his long career, lasting more than sixty years.

Gaetano Cipolla has always shared Buttitta’s passionate defense of the Sicilian language and the poet’s defense of the poor people of Sicily “who have struggled hard under foreign dominations, who have been forced to emigrate to different countries to find a more decent way to live and to sustain their families, who have been denied the right to work, ever bowing before the powerful, while suffering hunger and disease.” They both shared the “regret for the prejudices that have accompanied the good Sicilian people for centuries, for the stigma of the Mafia that has tarnished’ their reputations, for the “belief that Sicilian speak a mongrel language when, in fact, it was the first Italic language, emerging from Latin, worthy to be used in poetry.”

Because of these connections to the poet, Dr. Cipolla found it to be a privilege to lend his English voice to Buttitta’s poems. And what a marvelous work of translation he has done.

The reader may object to my own evaluation of the translation, being that I am not Sicilian and certainly do not speak that dialect, but if any Italian who has had even a limited exposure to Sicilian dialect, through friends or coworkers, will read Buttitta’s Sicilian verses, he will marvel on how easy it is to comprehend them. Buttitta’s language is crisp, clear, and immediate, especially when read aloud. Hence my ability, as a translator myself, to properly evaluate this translation.

The reader may object to my own evaluation of the translation, being that I am not Sicilian and certainly do not speak that dialect, but if any Italian who has had even a limited exposure to Sicilian dialect, through friends or coworkers, will read Buttitta’s Sicilian verses, he will marvel on how easy it is to comprehend them. Buttitta’s language is crisp, clear, and immediate, especially when read aloud. Hence my ability, as a translator myself, to properly evaluate this translation.

The choice of the poems is also optimal, offering a gamma of emotions and topics that were dear to the heart of the poet, “who had espoused early in his career a socialist ideology,” and desired to be remembered as “A poet who loved people.” Furthermore, the Sicilian language has a certain musicality to it, and it holds the power to move people, “reawakening in them things that have been dormant for many years, bringing back images and feelings that modern age has erased…”

So, when reading this anthology, the readers have various options offered to them, depending on their level of knowledge of each language (Sicilian, Italian, and English): read and appreciate the marvelous verses in the original language, read the English verses alone, or read both Sicilian and English verses.

No matter what options they choose, the result will be to love Buttitta’s poems because of their deep emotional message.

To reinforce this message and at the same time the importance of retaining our original languages, being them Sicilian, Neapolitan, Milanese, Venetian, or whatever else they may be, I conclude with the first two stanzas of Buttitta’s famous poem “Lingua e dialettu,” extracted from this marvelous anthology:

Un populu,

mittitilu a catena

spugghiatilu,

attuppatici

a vucca,

è ancora libiru.

Livatrici u travagghiu

u passaportu,

a tavola unni mancia,

u lettu unni dormi,

è ancora riccu.

Un populu

Diventa poviru e servu

Quanno ci arrobbanu a lingua

addutata di patri:

è persu pi sempri

A people

put them in chains

strip them naked

plug up

their mouths,

they are still free.

Take away their work

their passports,

the table where they eat,

the bed where they sleep,

they are still rich.

A people

become poor and enslaved

when you rob them of their language,

inherited from their forefathers:

they are lost forever.