An interview by Tiziano Thomas Dossena

An interview by Tiziano Thomas Dossena

A leading expert in the field, Fred L. Gardaphé is Distinguished Professor of English and Italian American Studies. He directs the Italian American Studies Program at Queens College, City University of New York, and works at the John D. Calandra Italian American Institute. Previously he helped to create the Italian American Studies program at Stony Brook University which he directed from 1998-2008.

Fred Gardaphé is Associate Editor of “Fra Noi,” an Italian American monthly newspaper,

editor of the Series in Italian American Studies at State University of New York Press, and co-founding-co-editor of “Voices in Italian Americana, a literary journal and cultural review.”

He is past President of the American Italian Historical Association (1996-2000) now known as the Italian American Studies Association, and served as Vice President of the Italian Cultural Center in Stone Park, IL from 1992-1998.

L’Idea Magazine: Hello Fred. You have ancestry both from Italian (Apulia and Basilicata) and French origins. How strongly do you feel about your heritage? While growing up, have you had the opportunity to be exposed to both of these countries’ traditions and customs through your family?

L’Idea Magazine: Hello Fred. You have ancestry both from Italian (Apulia and Basilicata) and French origins. How strongly do you feel about your heritage? While growing up, have you had the opportunity to be exposed to both of these countries’ traditions and customs through your family?

Fred Gardaphé: I spent the early years of my life thinking I was Italian and trying to be American. It seemed that inside the home and neighborhood I couldn’t get away from it, and outside, especially when I went to high school, I kept running into obstacles that I had to overcome to fit into the expectations of what it meant to be American back then. The further I moved away, through college and later, work, I began to think I was leaving the Italian behind. This was especially true in the late 1960s when we were more worried about politics in the U.S. and the world; then I was Italian inside the home and American outside of it. My grandparents were my greatest influences and on my mother’s side, they were more traditionally Italian in terms of food and traditions. My father’s mother practiced many of them and it was her dream that I learn to read and write Italian, as she could. We were surrounded in both homes with Italian food, music, and the language. But it wasn’t until I took my first trip to Italy when I was 25 years old that I was able to see Italian culture for myself and that’s when I realized, I wasn’t Italian nor was I the American I thought I was. That’s when I realized I could take what I wanted from each culture and turn it into being Italian American. That’s when I became, what I used to call, a born-again Italian.

L’Idea Magazine: It is obvious from your biography that your “Italianità” has influenced your career, but what about your personal life choices? Has it been as important in your life?

Fred Gardaphé: Italianità for me is taking what is good and healthy from Italian culture and applying it to my life. Whether is a way of dealing with people, presenting yourself publicly, or attitudes toward nutrition and living holistically, I have always searched for the indigenous truths and ways of being that come from my Italian heritage. I have come to call this process indigenuity: the acts of maintaining the truths that have served our culture well for centuries. This I see as the center of my life, and I have built both my personal and professional lives around this concept.

L’Idea Magazine: Queens College is my Alma Mater and at the time (1974-1976) I used to love spending many hours chatting about the world’s situation, Vietnam, discrimination and other topics with author Richard Gambino, who had just published “Blood of my Blood” and who had created the Italian American Studies Program at Queens College that you now direct (by the way, that shows how much interest and patience Gambino used to have…) Most Italian students, just like me, were very interested and involved with that program at the time, but many years have gone by since then…

Do you still find a lot of interest in the college students of today in these studies? Since then, changes occurred in our society. What do you believe this type of program stands for and offers to the students, nowadays?

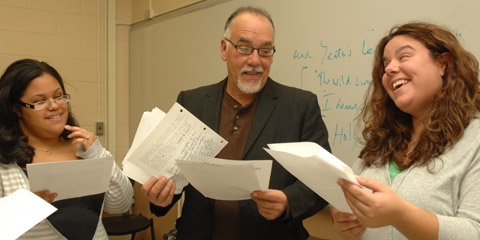

Fred Gardaphé: I find today that students who identify with their ancestral cultures do so on the family and public levels quite differently than those of my generation. Much of their knowledge comes from the media they consume, and so what I teach in the classes might ring a bell in their minds and help them understand the very things I took for granted growing up, or they are learning about it for the first time. I see more than Italian heritage students and so what I find is that what I teach offers all my students new information that challenges what they’ve been consuming and that’s always the high point of my experiences in the classroom. The programs I’ve developed and still teach serve both the Italian heritage student and the general student to strengthen and stretch their identities through an awareness of the impact Italy has had on the United States.

Fred Gardaphé: I find today that students who identify with their ancestral cultures do so on the family and public levels quite differently than those of my generation. Much of their knowledge comes from the media they consume, and so what I teach in the classes might ring a bell in their minds and help them understand the very things I took for granted growing up, or they are learning about it for the first time. I see more than Italian heritage students and so what I find is that what I teach offers all my students new information that challenges what they’ve been consuming and that’s always the high point of my experiences in the classroom. The programs I’ve developed and still teach serve both the Italian heritage student and the general student to strengthen and stretch their identities through an awareness of the impact Italy has had on the United States.

L’Idea Magazine: Was your literary interest focused on Italian Americana since your beginnings as a teacher?

Fred Gardaphé: I really didn’t pay attention to Italian American writers, save for Mario Puzo, when I was going through my early education. I’ve written a long essay on this discovery entitled: “Breaking and Entering: An Italian American’s Literary Odyssey.” Forkroads, (Fall, 1995): 5-14. Reprinted in Beyond ‘The Godfather’, 1997. This was a real breakthrough piece for me that helped shape the approach and voice I try to use in my writing. It’s a combination of journalism and academic styles that enables me to maintain the connection between the streets and the academy, which has been a theme of my education throughout my life. I did a high school thesis paper for my Senior Religion course on the Mafia; that was 1969, when Puzo published The Godfather. That was my first academic attempt to integrate my experience into my assignments. I didn’t get a good grade with that and so I abandoned the subject until I got to graduate school. I did my master’s thesis on Walt Whitman and was expected to go on for the Ph.D. with that subject. That’s when I discovered Rose Basile Green’s study The Italian American Novel, shortly after my first trip to Italy, and from then to this day, I haven’t shifted subjects in most of my writing and teaching.

L’Idea Magazine: You co-designed and co-directed the Italian Diaspora Summer Studies Seminar at the University of Roma Tre. What situations and problems did this seminar address? Was there a publication of the Seminar available to the public?

L’Idea Magazine: You co-designed and co-directed the Italian Diaspora Summer Studies Seminar at the University of Roma Tre. What situations and problems did this seminar address? Was there a publication of the Seminar available to the public?

Fred Gardaphé: It’s been difficult to get Italian American Studies, first into the undergraduate curriculum and even more so in the graduate curriculum, so we (Dean Anthony Julian Tamburri of the Calandra Institute and I) decided that if it was going to ever get done we needed to do it ourselves. So we set up a series of courses, recruited the top thinkers in the field, and created a seminar that would be held every summer for advanced graduate students and professors who wanted to do work in the Italian Diaspora Studies. We began with the University of Calabria, Rende, where we spent three summers (2015-1017), then with the help of Professor Sabrina Vellucci, moved it to Rome where it now takes place at Roma Tre University (2018 to the present). The seminar is designed to immerse our corsisti in various disciplines such as literary and film studies, the social sciences, history, and others, depending on who the faculty is each year while they are also experiencing life in Rome and to take the knowledge they gain from the sessions and put it to work in their disciplines; it’s a matter of gaining the knowledge to help them develop their own projects, such as dissertations, essays, book projects, and whatever work they wish to create with the material they study. Roma Tre provides the location and offers graduate credit to those who seek it. We hope to someday make the experience part of a permanent program in a graduate degree offering institution. Until then, the important thing is to make this type of study possible for those who seek it. Over the years, our students have gone on to complete their dissertations, created art exhibits, developed creative and critical projects that have all advanced knowledge in the field. While we don’t have a publication, yet, we do have plans to bring together all our past students for a conference when the time is right for such events, and perhaps a publication will result.

L’Idea Magazine: You wrote and edited many books. Your topics include Italian traditions, recipes, Italian American Studies, gangsters, literary reviews, etc. but mostly you seem to focus on Italian American literature. Am I right?

Fred Gardaphé: Ever since I returned from my first trip to Italy, in 1978, I’ve been infatuated with all things Italian. After that trip, I used to call myself a born-again Italian, and I did everything I could to connect to my ancestral homeland. There was so much I didn’t know about the culture, and as I kept learning more, I responded to that education in my writing. I had always wanted to write and really started when I was seventeen years old with that researched essay on the Mafia for my Senior year Religion class. While I have studied many aspects of English and American Literature, from the traditional canons to the many aspects of the U.S.’s multicultural kinds of literature, my focus became Italian and Italian American subjects, because, as Toni Morrison once said, “I wrote the books I wanted to read.”

L’Idea Magazine: Your book “Italian Signs, American Streets: The Evolution of Italian American Narrative (New Americanists)” has been defined as ‘the first major critical reading of Italian American narrative literature in two decades.” Could you tell us more about it?

L’Idea Magazine: Your book “Italian Signs, American Streets: The Evolution of Italian American Narrative (New Americanists)” has been defined as ‘the first major critical reading of Italian American narrative literature in two decades.” Could you tell us more about it?

Fred Gardaphé: It’s a book, so it’s hard to describe in a few words. Every book I write answers questions that I need to have answered. For this one, it was, what is Italian American literature, if there is one, and why aren’t there any books out there on the subject. This book happened when I was in graduate school, doing research for my master’s thesis on Walt Whitman. As I was walking to the shelves that held his books in the stacks of Memorial Library at the University of Chicago, I passed E. 184, and Rose Basile Green’s The Italian American Novel caught my eye. I grabbed it and read the whole book sitting in those stacks. I had been in Italy the previous summer and was well into my born-again-Italian phase. That book was the start and that’s when I decided I was going to take her work further through my own. In my study, I had wanted to create a more sophisticated approach to the reading of these novels. The first thing I did was to track down nearly all the novels about which she wrote and read them. My goal was to read every novel ever written by an American of Italian descent; while I don’t think I ever really achieved that goal, I read hundreds and my responses began bubbling over and found their way into a systematic study that I created based on the philosophy of thinkers such as Giambattista Vico and Antonio Gramsci. Helped by the criticism of other ethnic American literatures, I began to formulate an approach to the study and interpretation of Italian American literature. I applied that framework to several works that reflected the reach of Italian American writers over the twentieth century. While I couldn’t do the work at the University of Chicago, I did find a way to do it at the University of Illinois at Chicago. I was motivated enough to make the transition and get the work done. Then I sent it off to Duke University Press and the rest is literary history.

L’Idea Magazine: What is your 2006 book “From Wiseguys to Wise Men” about?

L’Idea Magazine: What is your 2006 book “From Wiseguys to Wise Men” about?

Fred Gardaphé: The is the academic public face of my life. When I wrote this, I was just getting into psychotherapy for the first time in my life; just so happens it was during the same time that The Sopranos first aired, and as I was watching it, I remember saying to myself; that’s not what a real gangster would do in therapy. So I started wondering what it would be like to tell my life story, and because I was still afraid to do so, for many reasons. I thought I could approach the subject from an academic perspective to explain why everyone was so obsessed with the gangster figure in storytelling, from news accounts to Hollywood films. I remember when I gave my first talk on the subject at St. John’s University in Queens, a New York judge was in the audience, and after the talk, we happened to meet each other in the bathroom, and he told me that I shouldn’t waste my skills and time on the gangster figure when there were so many good things about Italian culture that could be explored. I asked him, “Is cancer a bad thing?” And he said certainly it was. Then I replied, “Would you tell a doctor to stop researching cancer because it was a terrible thing to dwell on?” He looked at me, quite puzzled, and said, “What are you getting at?” I left him with, “Well if the gangster figure is the cancer of Italian American culture, shouldn’t someone try to figure out why?” That became my impetus to study the figure of the gangster in storytelling from myth to non-fiction and then fiction. I put forth a theory that the gangster was an archetype, the type that Freud and Jung used to explain human behavior, and followed it through an overview of the films, stories, and paintings in which the gangster played a major role, explaining along the way why this figure continued to capture the imagination of artists and their audiences for centuries. I wanted to put it all into some perspective into the understanding of how models of masculinity required this figure and end by providing a sense of why this happened and what might happen if we spent as much time promoting the wise men of our culture.

L’Idea Magazine: Is “Leaving Little Italy: Essaying Italian American Culture” about the changes in Italian American society or is there more about it?

L’Idea Magazine: Is “Leaving Little Italy: Essaying Italian American Culture” about the changes in Italian American society or is there more about it?

Fred Gardaphé: This was a transition book for me, as I moved from literary studies into studies of the social sciences. I wanted to explain how culture continues to live when the place it was created was gone. My mother’s father and mother lived in Italy; they moved to the U.S. and lived in what was called “Little Italy,” where my parents and I grew up. By the time I had my own children, that place had changed and so they grew up in the plain, old U.S. I wanted them to have a sense of what it was like and so began the book with a literary-historical overview of the experiences of the first and second generations of Italian immigrants and their children, moved into a discussion of how Italian identities were shaped by elements of race, class, gender, sexuality, and foods. I put to work my earlier studies of history, sociology, psychology and so much more. The book was born in talks and articles I had earlier presented and published, and as I reworked them they coalesced into the book.

L’Idea Magazine: Could you tell us a little about “Introducing Italian Americana: Generalities on Literature and Film, a Bilingual Forum”, which you co-wrote with Paolo Giordano and Anthony Tamburri?

L’Idea Magazine: Could you tell us a little about “Introducing Italian Americana: Generalities on Literature and Film, a Bilingual Forum”, which you co-wrote with Paolo Giordano and Anthony Tamburri?

Fred Gardaphé: This was a very simple book that originated from a two-day symposium held at Florida Atlantic University dedicated to the integration of the Advanced Placement exam within the teaching of Italian language and culture. The two-day symposium was organized by Professor Myriam Swennen Ruthenberg, chair of Languages, Linguistics, and Comparative Literature. The first evening was dedicated to Italian American culture, and the second consisted of a general workshop on the teaching of Italian in high school and how to prepare students for the Advanced Placement Exam, organized and led by Rosa Bellino Giordano, a member of the Educational Testing Services team of specialists in Italian language teaching. My contribution was the reprinting of an essay I had published, entitled, “From the Old Country to the Old Neighborhood: Creating Italian American Literature.” Paolo A. Giordano’s contribution was “From Italy to the New World: Italian Writers in the United States,” and Anthony Julian Tamburri’s essay was entitled, “Italian Americans and the Movies.” The book was published bilingually and designed to introduce readers to the world of Italian American literature and film.

L’Idea Magazine: “From the Margin, Writings in Italian American,” which you also co-edited with Paolo Giordano and Anthony Tamburri, is more than an anthology, isn’t it?

L’Idea Magazine: “From the Margin, Writings in Italian American,” which you also co-edited with Paolo Giordano and Anthony Tamburri, is more than an anthology, isn’t it?

Fred Gardaphé: It is an anthology and only the second in the history of Italian American literature, the first being Helen Barolini’s The Dream Book. This work evolved from three papers presented by Tamburri, Giordano, and myself at the Twentieth Century Literature conference back in 1989. After the conference, we decided we needed to find a place to publish our papers, which had a mixed reception at the conference. The audience was composed primarily of Italian professors, many of whom were of Italian ancestry. One of the criticisms of our panel was that many in attendance thought we were placing these very American writers in a ghetto by referring to them as Italian American writers, that they were really American writers, and shouldn’t we just leave it at that. That became a gauntlet of sorts that led us on the path of taking the study of Italian American literature quite seriously. We decided to send out a call for submissions to contribute to a book that would be the first anthology of Italian American literature and criticism, and unlike Barolini’s pioneering work, which contained only women writers, we decided to open the doors and publish the best of what came in. Our first submission to a publisher was rejected, and by the time Purdue University Press agreed to publish it, we had gathered more material than a single book could have contained. That’s when we decided to form Bordighera Press and through it publish many of the works that didn’t get into the volume in a journal that we called, Voices in Italian Americana (VIA). Today, more than thirty years later, VIA is still published twice a year. The anthology, still in print, contains poetry, short fiction and critical essays that have been taught in courses throughout the country and in Italy. When I look back, I see it as one of the most important publications in which I’ve been involved. We produced a second edition a few years ago, and the work still holds up.

L’Idea Magazine: What about “Read ‘Em and Reap: Gambling on Italian American Writing”? What is it about?

L’Idea Magazine: What about “Read ‘Em and Reap: Gambling on Italian American Writing”? What is it about?

Fred Gardaphé: Read ‘Em and Reap is the third collection of the book reviews I have published since my first in 1985 in the Fra Noi newspaper of Chicago. The first, entitled Dagoes Read: Tradition and the Italian American Writer and since then, I’ve published a volume every ten years of my book reviews, most of which have appeared in the Fra Noi, VIA, and a few other venues. The second was The Art of Reading Italian Americana. Read ‘Em was published in 2017. Together they represent the result of my attempt to keep up to date with what is published by and about Italian American writers and culture. There was a time, way back when I began, that I could say I had read everything written about the subject. Today, I can’t even say I know what’s being published. The field has grown that much and I’m very happy to have been a part of its growth. I supposed there will be at least one more volume, that will collect the work from 2016-2026, but that’s a few years off.

L’Idea Magazine: It is apparent that you are very involved with the Italian American literary world and that most of your writing is about other writers’ work, but you also published a book of short stories in Italian and you are working on the English version (to be published soon). It was somehow a reverse process since the stories were originally written in English. Could you tell us more about your “Importato dall’Italia”?

Fred Gardaphé: Importato dall’Italia was my first published collection of short stories; a couple had appeared separately in various publications over the years such as Fra Noi, and the title story won an Illinois Arts Council award and a UNICO prize for writing. Many of the stories never appeared in print and found their way into print first through this Italian translation, which was done by journalist Silvana Mangione. I never really had thought of publishing a book of stories until Ms. Mangione approached me with the idea, and brought it to Idea Press. Most of the stories capture the Little Italy where I grew up, Melrose Park, Illinois and recount the experiences of young and old characters based on people I actually knew, though through fiction they might not appear exactly as they were. If you lived there, you would recognize many of them, but if you don’t then they might remind you of people who grew up in your old neighborhoods.

Fred Gardaphé: Importato dall’Italia was my first published collection of short stories; a couple had appeared separately in various publications over the years such as Fra Noi, and the title story won an Illinois Arts Council award and a UNICO prize for writing. Many of the stories never appeared in print and found their way into print first through this Italian translation, which was done by journalist Silvana Mangione. I never really had thought of publishing a book of stories until Ms. Mangione approached me with the idea, and brought it to Idea Press. Most of the stories capture the Little Italy where I grew up, Melrose Park, Illinois and recount the experiences of young and old characters based on people I actually knew, though through fiction they might not appear exactly as they were. If you lived there, you would recognize many of them, but if you don’t then they might remind you of people who grew up in your old neighborhoods.

The title story was based on an actual experience I had after I had returned from my first trip to Italy. I started looking for Italy in the U.S. and when I found it, either captured it in a story for the Fra Noi, or if that wasn’t possible, I’d rework the real experience into fiction through my imagination. Many of the stories deal with old people, the original immigrants to the area, whom I had grown up around and who very much influenced my interest in the old country. “Vinegar and Oil” was written as a story, and when I first did a public reading of it, Italian author Giose Rimanelli told me that it wasn’t a story, but a play. I reworked it and the Italian American Theater Company of Chicago produced it to great success. The title story also became a play that was produced by Zebra Crossing Theater of Chicago. I look forward to publishing the original English language stories so that finally the survivors of Little Italy and their descendants can enjoy them.

L’Idea Magazine: That was not the only work by you that appeared in Italian, was it?

L’Idea Magazine: That was not the only work by you that appeared in Italian, was it?

Fred Gardaphé: My study, Italian Signs, American Streets: The Evolution of Italian American Narrative, was published in translation by Franco Cesati Editore in 2012, beautifully translated by Alessandra Senzani. I’ve had a number of essays and poems translated and published in Italian, but these were the only two books of mine translated and published.

L’Idea Magazine: I understand that three tragedies in your families (the loss of your grandfather, father, and godfather) had also a certain influence on the type of topics you choose to write about in your nonfiction books, but is it going to be the same in your future fiction work?

Fred Gardaphé: The stories of the tragic deaths of the three most important men in my life, and for whom I was named, have been with me since I’ve been seven years old, when my godfather Louis was killed; then when I was ten my father was killed, and when I was fourteen, my grandfather. Certainly, these three traumatic events have affected everything I have done since in many ways. My entry into the study of Italian American culture was a way for me to come to some understanding of the culture that provided the contexts for these killings. I was drifting away from the personal experiences during my early days of research, but as the years passed I kept being pulled to this material. You could say it came out, under an academic cover, in my From Wiseguys to Wise Men book, but I was still a bit distanced from it all. Now that I’ve achieved what I wanted from my academic work, I can more easily approach the material that I’ve been writing, but not publishing for many years. Sometimes it takes a while to get at the heart of what it is a writer should be doing. My main problem was that I made a career studying my life and could use so very little of it in the work it took to become a distinguished professor. Now that I’ve arrived, I can return to that material and see it in new ways. My goal is to publish either a memoir or a novel and do a one-man show based on some of those experiences. These are the projects that excite me as I enter the twilight of my career.

L’Idea Magazine: You have been writing a Memoir provisionally titled “Living with the Dead.” Is it close to being completed and published?

L’Idea Magazine: You have been writing a Memoir provisionally titled “Living with the Dead.” Is it close to being completed and published?

Fred Gardaphé: I’ve been writing my life experiences since I was seventeen; sixty-two years later I have thousands of pages of unpublished (some of it almost published) writings that appear as fiction and non-fiction. Versions of these have been worked on with titles such as “A Generation Removed,” “Living with the Dead,” “The Good Professor,” and many more. This is the real work of me, the writer. Most of what I have written will never be published, but it seems I’ve been writing it all along to keep it all alive. I have film treatments and scripts, poems; I’ve never stopped trying to shape my experiences into some form of literary expression. Maybe someday one or more will find their way into print.

L’Idea Magazine: You had a column in the periodical “Fra Noi,” and from it the book “Moustache Pete Is Dead!: Evviva Baffo Pietro. The Fra Noi Columns 1985-1988” was born. You also had a one-man show at the Chicago Historical Society based on the book… Could you tell us the topics of the articles that you collected in this volume?

L’Idea Magazine: You had a column in the periodical “Fra Noi,” and from it the book “Moustache Pete Is Dead!: Evviva Baffo Pietro. The Fra Noi Columns 1985-1988” was born. You also had a one-man show at the Chicago Historical Society based on the book… Could you tell us the topics of the articles that you collected in this volume?

Fred Gardaphé: I think this is one of the most important projects I’ve done so far. It began with my first trip to Italy when I was twenty-six. On my return, I kept being flooded with memories of my mother’s father Michele. Grandpa Michele was Italy to me when I was young, more so than my other grandparents. Going back to where he and my grandmother were born, to Castellana Grotte in Puglia, was one of those “my life will never be the same again” moments. I kept hearing his voice in my head. It was as comforting as it was haunting. A few years later, when I had kids, I wanted them to hear his voice as well, so I decided to write a column for the Fra Noi, a newspaper I used to read to him in English. He would have been considered a “Moustache Pete,” a male immigrant who clung to the old country ways and styles in his life.

What I had learned during my visits to Italy was that he was wise beyond my earlier considerations, and while he led a simple life, he was much more complex than I was aware of when I was younger. Every month, I would sit down with a glass of wine and imagine that I was him, writing a column to today’s Italian Americans. Using memories of his life, and capturing his voice in precise Italian American English, I would write these columns and wanted to find a way to get them into print. I created a fictional context that seemed real. At the time I was also interviewing residents of an Italian American retirement home outside Chicago called Villa Scalabrini, so I was gathering a great deal of information and history of the people I met. I combined my grandfather and these first immigrants from Italy in their old age to create Moustache Pete. I don’t think I’ve ever had more fun with a project. “Pete” received hate and love letters and caught on well with the readers. Then a new editor took over and decided to cut the column because he thought it didn’t portray Italian Americans in a good light. You see Pete would criticize today’s generations for what they had forgotten about the past and for how they lived their lives as “mericans”.

A few years later, when we started Bordighera Press, I decided that these columns were worth preserving in print and published them with the subtitle, “Oral Tradition Preserved in Print.” This happened while I was writing my dissertation and was deeply involved with locating the origins of Italian American literature and documenting its transition from oral to written registers. The monthly columns would deal with seasonal events such as the holidays, feste, Columbus Day and filled with proverbs that my grandfather and others of his generation passed along during their lives. It truly was a work of love, a way of repaying my earlier feelings about how old-fashioned my grandfather was in the America I was growing up in. It really was my way of staying in touch with Italy when I couldn’t be there, and keeping the old ones alive in our culture, long after they had passed on.

A few years later, when we started Bordighera Press, I decided that these columns were worth preserving in print and published them with the subtitle, “Oral Tradition Preserved in Print.” This happened while I was writing my dissertation and was deeply involved with locating the origins of Italian American literature and documenting its transition from oral to written registers. The monthly columns would deal with seasonal events such as the holidays, feste, Columbus Day and filled with proverbs that my grandfather and others of his generation passed along during their lives. It truly was a work of love, a way of repaying my earlier feelings about how old-fashioned my grandfather was in the America I was growing up in. It really was my way of staying in touch with Italy when I couldn’t be there, and keeping the old ones alive in our culture, long after they had passed on.

L’Idea Magazine: A few years back, you were the host of the weekly talk show “Italian Signs, American Streets” on the “Dolce Channel”. What was the show about?

L’Idea Magazine: A few years back, you were the host of the weekly talk show “Italian Signs, American Streets” on the “Dolce Channel”. What was the show about?

Fred Gardaphé: This was my “Fifteen minutes of success” on cable television. Long before there were streaming and podcasts, William Medici had a plan to do an Italian and American television network and he started with the Dolce Channel. My program was the brainchild of Anthony Julian Tamburri who wanted to expand the work he was doing with the CUNY-Cable television show, “Italics,” through the Calandra Institute, which he produces and hosts. My part was simple, host conversations with key artists in the Italian American communities around the country. Shot on location in New York from a Mulberry Street Little Italian restaurant, the program featured painters, photographers, writers, musicians, filmmakers, actors, theater producers and more… It was a lot of fun, but like most innovative and interesting work by Italian Americans, the lack of stable financial support kept it from becoming the media institution that we had hoped it would be.

L’Idea Magazine: You also appeared in five Documentary Films…

Fred Gardaphé: What can I say, I’m a sucker for performing possibilities, probably a result of my early, early work in the theater and people’s radio while I was a student at the University of Wisconsin in the mid-1970s. I’ve been interviewed for many television and film documentaries that deal with the Italian American experience. From “And They Came to Chicago,” to the PBS backed “The Italian Americans” and many that focused on organized crime: “Beyond Wiseguys,” “The Godfather Legacy,” “Gotti: Godfather and Son,” and a few more. It comes with the work I do, and I rarely say no.

L’Idea Magazine: Are you working on any other literary work at this moment?

L’Idea Magazine: Are you working on any other literary work at this moment?

Fred Gardaphé: Right now, I’m trying to complete a project I’ve been working on for too long, at least since 2008, a study of humor and irony in Italian American culture. That’s more academic, but it includes analysis of literary and media presentations that reflect the history and development of these ideas. I’m always working on something. I have the start of a novel that compares the travels to Italy of a grandson to his grandfather’s travel to the U.S. It’s done in alternating chapters, with each trying to figure out how to fit into their new environments. I have also started a collection of short stories called “Alter Boys,” the title story of which was featured in your second “Feast of Narrative” series of publications. I’m hoping to get out the original English version of Importato dall’Italia, as well as a one-man show, tentatively entitled, “Through the Loupe,” which deals with my years growing up in my grandfather’s pawnshop. I also have a memoir that I’ve tried to get published, called “Blood Stains,” that deals directly with the tragedies that took place in my family. Another project I’m working on is a word/image project that started with the Italian Australian artist Filomena Coppola. From the first time, I saw her work I was intrigued and that began a collaboration that’s been happening throughout this pandemic. Not sure where it’s headed, but I do find we have different ways of saying the same things. In sum, I’ve got more than enough to keep me busy for the rest of my life.

L’Idea Magazine: One of your essays appeared in the book “Anti-Italianism,” which you also co-edited. Do you feel that anti-Italianism is still alive and thriving?

L’Idea Magazine: One of your essays appeared in the book “Anti-Italianism,” which you also co-edited. Do you feel that anti-Italianism is still alive and thriving?

Fred Gardaphé: While it’s certainly not what it used-to-be, I think Anti-Italianism stills exists, not in the more dangerous old overt ways that led to discrimination and lynchings, but definitely in more covert ways, and will remain until Italian American stories work their ways out of the shadows of the stereotypical productions that cemented the distorted images we still consume of our culture. I can say that I’ve faced a great deal of anti-Italianism in of all places, the ivory towers of our country. That there’s still no permanent place for Italian American studies at the graduate level in the state of New York is a testament to this phenomenon. It’s anti, not because there are forces out there keeping us from establishing such programs, but in the sense that very few U.S. institutions are aware of the need for them. Many of us have been working to create endowed professorships of Italian American studies throughout the country, and we’ve had some great success; but when it comes to permanently institutionalizing formal studies at all levels, the forces of ignorance that we run into has been quite disheartening. I won’t rest, or be laid to rest, I hope, until higher education recognizes this need, and the Italian American community realizes its responsibility to demand and support these efforts. Had this been done generations ago, as done by many other ethnic groups in this country, the lingering anti-Italianism would have become a thing of our past, instead of something we keep having to confront.

L’Idea Magazine: If you had the opportunity to meet and talk with a person from the past or the present, anyone you choose, who would that person be, and what would you like to ask?

L’Idea Magazine: If you had the opportunity to meet and talk with a person from the past or the present, anyone you choose, who would that person be, and what would you like to ask?

Fred Gardaphé: I talk to the past all the time, through my reading and my memories of my own experiences, so the list would be quite long. I’d love to have conversations with many of the authors who have entertained and influenced me over the years: Mark Twain would be near the top, as would be Machiavelli, Dante, Julius Caesar, and hundreds of others. From my own life, I’d love to go back for a dinner, at least, with my grandparents, and talk to them about my experiences of going back to Italy and how it changed where I was headed with my life before that first trip in the summer of 1978. I’d also want to talk to the men who committed the crimes against my family. Not sure what I’d do with all that information, but it would be fun to have those experiences.

L’Idea Magazine: Throughout your life, have you been to Italy a lot? If so, did you find it quite different from the country that the previous generation of Italian immigrants was describing?

L’Idea Magazine: Throughout your life, have you been to Italy a lot? If so, did you find it quite different from the country that the previous generation of Italian immigrants was describing?

Fred Gardaphé: When I visited Italy for the first time, I kept thinking how could my grandparents have ever left this place? When I returned, I began my lifelong study of Italian and Italian American cultures that led to the work I do; through that, I understood exactly why my mother’s father was the only one of his family to come to the U.S. He also had a sister who had married and gone to South America, Argentina, and many cousins as well. I also came to know the many traumas my family experienced and how those were transmitted subconsciously to the next generations. This led me to begin telling their stories.

The family I met back then was financially a generation behind ours in the U.S., but within five years, that changed. When I first arrived in Castellana Grotte, I was surprised to see television antennae atop buildings and homes. My grandfather had never described them in his stories, and of course because he arrived in the U.S. in the 1920s. In the hearth of the trullo where he had grown up a television set, instead of a fire. During that trip, I learned that the Italian I thought I was speaking was an old version of the dialect they spoke in the town. My family in Italy used to tease me when I spoke; my grandfather’s brother once brought me down to the Piazza Garibaldi where is old pensioner friends would gather each day and talk. They kept prodding me to say words and phrases; one came up to me, pinched both my cheeks and said I was so young to speak so old. I was speaking the dialect as it was when my grandfather had spoken more than nearly sixty years earlier.

I have been visiting Italy for the past forty-four years and can say that it has changed very much in many ways, and very little in some ways as well: materially more than spiritually, or so it seems to me. I was able to live in Italy once for six months during a Fulbright professorship I was awarded at the University of Salerno. That’s when I realized that Italy wasn’t all the beauty and ease of life I had experienced as a carefree tourist. I would say that the quality of life in Italy is so much better in Italy than here in the U.S., especially in terms of food, sense of time, balance of work and life, and social camaraderie. While it’s not the haven it was for me back in the late 1970s and 80s, it’s become a place in which I feel very much at home and have missed so much during this pandemic. I look forward to my return this year.

L’Idea Magazine: A message for our readers?

Fred Gardaphé: For your own sake, read Italian American writers, support their work, and become modern-day Medicis, without whom many of the masterpieces we associate with Italian culture would have never been realized and popularized.