Italian Americans: The Progressive Tradition–Reflections on Gerald Meyer’s Presentation at the New Haven Public Library

By Roberto Ragone and Stephen Siciliano

In contrast to their present-day placement at the conservative end of the political spectrum, Italian Americans once played an under-appreciated role in the “Old Left” progressive movement.

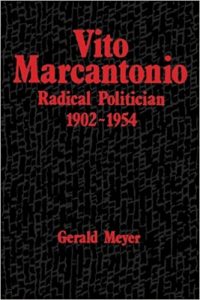

Such was the thrust of a recent presentation by Dr. Gerald Meyer, author of Vito Marcantonio: Radical Politician (1902-1954) to the New Haven Public Library. The author of Are Italians White? and The Lost World of Italian American Radicalism, Meyer asserted that Italian Americans were not merely quiet, committed, and loyal followers of leadership from beyond their community, but homegrown instigators for social justice.

To read this article as a PDF document, please click on this link…

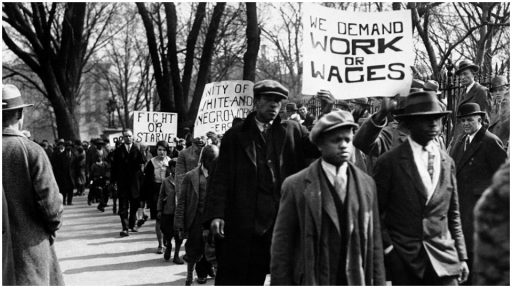

The Old Left, Meyer said, emerged in the first half of the 20th century, peaked during the New Deal Era under Franklin Delano Roosevelt.

The Old Left, Meyer said, emerged in the first half of the 20th century, peaked during the New Deal Era under Franklin Delano Roosevelt.

Until it was repressed in the aftermath of World War II, the Old Left thrived in a time of forceful, yet peaceful, protest, where constructive radicalism was, rather than stigmatized, “de-stigmatized.”

It was a movement that invoked American historical figures and the U.S. Constitution to advance social justice and set out to help constituencies meet their basic needs and mobilize them to form a more perfect union and ensure equality of opportunity and protection under the law.

Antecedents dated back to Gilded Age opposition to the Robber Barons and the subsequent industrial battles such as the 1937 Little Steel Strike (The Memorial Day Massacre), which resulted in 23 dead or wounded, included their fair share of Italian American casualties.

Dr. Meyer, co-founder, and co-president, of the Vito Marcantonio Forum (VMF), elaborated upon his doctoral thesis which posited that Italian American progressivism was a logical extension of the group’s prior experience in the Old Country.

Italian Progressives in Light of Traditional Stereotypes

Newly arrived Italians, and their descendants, were treated within these movements as younger step-siblings by the older immigrant groups, such as the Irish Americans and Jewish Americans, rather than as an ethnicity capable of affecting positive change in their own right.

Scholars and scribes have often portrayed New York City’s Mayor La Guardia (1882-1947) and Rep. Vito Marcantonio (1902-1954) as anomalies in an otherwise traditional, conservative, and reactionary Italian American milieu.

For these writers, La Guardia’s Jewish mother is viewed as a root cause of his progressivism rather than his Italianità, which ignores the rich and entwined history of Italy and its Jews, dating back to Rome; forgets the extraordinary protections Italy afforded them during the Holocaust or the academic work suggesting that Italian Jews were more likely to identify with their home country than with their tribal ethnicity, and more so in comparison to the experience in other European countries.

In the late 1800s and early 1900s, said Meyer, “one could have visibly seen Southern Italy transforming from feudalism to capitalism.” Boasting one of the Europe’s largest socialist parties before World War I, Italy saw it grow even stronger in the post-war period.

Semi-professionals—notaries, dentists, morticians, pharmacists—were the progenitors for radical activity on the peninsula. These literate professionals, who were catalysts for the Italian workers’ movement, did not come to America in large numbers, where they might have played a radicalizing role, because that would have meant a loss of social status.

Meyer noted that, while many craftsmen did come to America, their skills did not match the needs of an industrialized economy. Of these artisans only barbers, seamstresses, could find work, while cobblers, carpenters and metal workers were destined to become proletarianized.

The impoverishment and oppression experienced by participants in the Italian diaspora served as a logical springboard for progressivism and radicalism in the United States and spearheaded the cultural approach informing that activism.

In Italy, these craftspeople, along with the Italian contadini (peasants) were skeptical of the three “p’s” of authority: priests, police, and politicians, and a form of anti-Establishment, anti-clerical skepticism rooted itself and played out dynamically in the political struggles of Southern Italy.

To these three “p’s” would be added a fourth upon settlement in the U.S. – the press.

Italians in America looked askance at the media’s depiction of Italian immigrants and racist incidents, such as the lynching of Sicilians in New Orleans, and the execution of the anarchists Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti, or the inaccurate coverage of leaders Marcantonio and influential educator and community leader, Dr. Leonard Covello (1887-1982).

Studies of Italian American radicalism have focused on anarchism – manifested in the labor strikes in Lawrence, Mass (“Bread and Roses”) and Paterson, New Jersey’s textile industry. These earlier movements receded with the execution in 1927 of Sacco and Vanzetti. Although international protests called for their acquittal, anarchists of the day did not capitalize on the status of their case as cause celebre.

“These radical movements, for the most part, did not spend sufficient energy on publishing any propaganda, but rather on prefiguring a utopian life,” Meyer observed.

Collaborative Efforts: The Garibaldi Society, L’Unità del Popolo , WWI, and the Communist Party

Meyer’s New Haven Library presentation focused on the union movement and labor organizing by the Garibaldi Society, the International Workers of the World (Wobblies), the Communist Party’s Italian-language newspaper L’Unità del Popolo between the 1920 and ’40s.

The Wobblies, Garibaldi Society, and L’Unità (which included Marcantonio on its directing board) became voices for Italian American Workers, other laborers, immigrants, and African Americans. They provided cultural activities of the “high” type such as musical performances, theater productions, and educational gatherings such as picnics and lectures.

They did not attempt to “assimilate” or “Bolshevize” these workers, supporting instead cultural pluralism in contrast to the efforts of government and social workers to Americanize their lives. They respected the language and culture of the immigrant group, provide a welcome respite for Italians being told by such agents of homogenization to replace olive oil with the healthier American alternative, butter, which, culinary history and anthropology would later disprove.

L’Unità del Popolo encouraged Italian Americans to be active in the union movement. The Garibaldi Society and the L’Unità worked with Italian immigrants using the English and Italian languages. They did not criticize the mafia or the way Italians practiced Catholicism.

“Differences were adjusted to reach out to constituencies versus, say, the Daily Worker, which criticized LaGuardia for opposing the Non-Aggression Pact between Russian and Germany,” explained Meyer.

L’Unità provided ample coverage on the American Labor Party (ALP), which was formed in 1935 so that pro-labor and/or pro-socialist voters could support President Roosevelt’s reelection without pulling the lever for the Democratic Party.

By 1937, La Guardia and Marcantonio have migrated over from the Republican Party, where they had run as progressives against the Irish-dominated Tammany Hall Democratic machine. La Guardia would maintain his ALP affiliation until the day he died in Sept. 1947. Marcantonio remained in the ALP until Nov. 1953, after which he resigned in response to those who’d broken ranks to support the Democratic ticket for mayor and a watered-down progressivism.

Under Marcantonio’s chairmanship, the ALP often brokered negotiations between the Democratic and Republican parties, holding, as it did with its supporters, the key to victory in Gotham electoral contests. The ALP, which generated literature in Italian, Spanish, Yiddish, and German, enjoyed a plurality in New York’s growing Puerto Rican communities and was the second most powerful force in Bronx politics.

L’Unità documented the ALP’s groundbreaking efforts such as the nomination of the first African-American Congressman and Council Member in New York City, along with the first Puerto Rican public official, and myriad Italian American candidates.

The newspaper, together with the Wobblies, promoted the ALP agenda, which it shared when it came to opposing prejudice against foreign-born (and thus, working with the National Association for the Protection of the Foreign-Born) and fighting discrimination based on race, color, or national origin.

When the anti-communist witch hunts began after World War II, many suspected of party activity, or some other form of “radicalism” were indicted and/or deported. A major concern of these victims was separation from their families. Such was the case of L’Unità’s editor, whose wife and kids ultimately returned to Italy with him.

Left-of-center newspapers such as L’Unità were driven out of existence during the period. The Federal Government arbitrarily declared the Garibaldi Society to be a political organization, rather than a mutual aid society, and confiscated $65 million worth of workers’ insurance funds, forcing the sale of its properties.

At the time of these purges, the Communist Party had approximately 100,000 members; the ALP over 125 headquarters across New York State.

The break-up of these movements cut many progressive Italian Americans adrift, and they no longer associated with alternative, progressive causes.

Italian American Progressivism as a Cultural Response to Stunting Bureaucracy

The drive to advance progressive goals in the Italian American community can be attributed to a transplanting of the personalized, horizontal, interactive relationships typical of Italian towns (paese) in response to the “3-P” authorities operating primarily within bureaucratic, hierarchical relationships in the U.S.

This cultural conflict played out against the authority of Irish Americans, who had exclusive control of the Catholic organizational structures, which informed by Jansenism; a Catholic strain of Calvinism configured through a kind of schism that had occurred in Ireland.

“Jansenism,” Meyer stated, “was cold, rule-bound, fear-inflicting, and punishing.” In fact, most Italian Americans sent their children to public schools rather than the Irish-run Catholic educational institutions.

Similarly, Democratic Party machines, such as the Mayor Frank Hague’s in Jersey City and New York’s Tammany Hall, were controlled by the Irish, while unions’ control was split between the Irish and Jewish Americans. All were hostile towards Italians.

These cultural differences were also reflected in the economic disadvantages of Italian Americans who were segregated into inferior tenement housing where the bathroom was located in the common hallway and shared by multiple units. The Irish tended to live in brick houses or in apartments where the plumbing was indoors.

Meyer described Italian Americans as inhabiting “a Galapagos of different communities.” Covello described Italian Harlem, the largest Little Italy in the United States, as a “galaxy of similar families.”

In many localities, Italian Americans were more segregated than African Americans. This problem was compounded by the fragmentation and insulation of Italian-American communities according to Italian region, Italian town, and family itself.

Community Leadership and Direct Contact Brings Italians to National Prominence

Just as Italian Communist Party founder Antonio Gramsci talked of the need for “organic intellectuals” to emerge from a community as its leaders, La Guardia, Marcantonio, and Covello serve as models for public policy case studies in the area of political leadership, innovative community-centered education, bilingual education, cultural pluralism, de-escalating racial tensions, and community-based collective action.

This triumvirate underscored the effectiveness of leadership vested in, and intimately connected to, the local community in which they reside. In other words, the leaders and followers must come from the community affected by the activism, rather than initiated from (and certainly not violently instigated and provoked by) agents beyond its borders.

Covello’s innovative educational methodology critiqued the negative aspect of Italian American life. Dr. Meyer has stated in his prior presentations that Dr. Covello, more so than other Italian- American, “envisioned and defined” a constructive and engaging “alternative path for the Italian-American identity.”

First, as a teacher responsible for New York City’s approval of Italian as a Regents-credit language of study, and then as the principal of Benjamin Franklin High School, Covello emphasized the importance of learning one’s parents’ language and “first culture” in acknowledgment the of the immigrant experience’s value.

This was broadened, Dr. Meyer observed, to foster the appreciation of different races, ethnicities, and religions through cultural pluralism and community-centered education. Covello’s idea was to organize the neighborhood around the school into a multiracial, multi-ethnic, ecclesiastic, ecumenical coalition of teachers, parents, children, and local stakeholders, with an eye to improving local conditions both during and after the school day.

This educational model and methodology also underscored the emphasis in the Italian cultural experience of the horizontal, interactive relationship over the vertical, hierarchical, bureaucratic one.

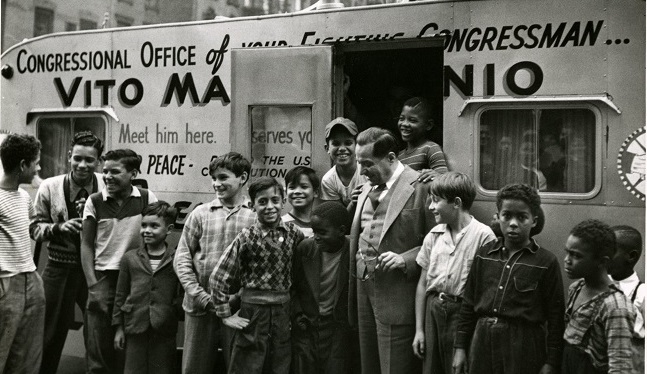

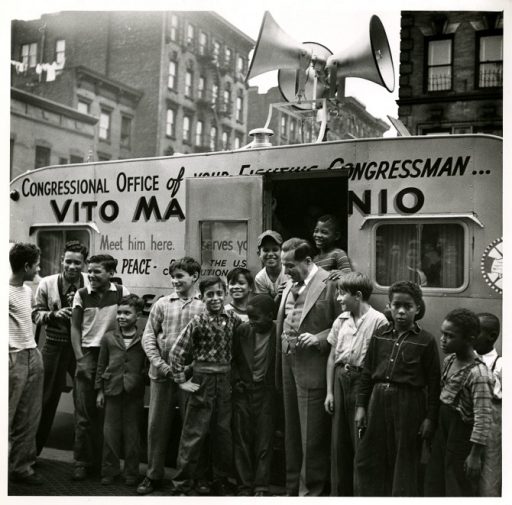

For his part, Marcantonio became a phenomenon by living his entire life within a four-block radius around where he was born while gaining national name recognition. As Congressman, he met with as many as 300 constituents every weekend, face-to-face in his office (not counting the number of households he met when he was aid-de-camp of La Guardia’s local, Congressional office), and developed a lasting connection with his constituents.

This enabled him to explain in townhalls why he voted in a controversial manner on issues less germane to local concerns. These included his opposition to the persecution of communists and intervention in the Korean War in 1950, when he cast the only “no” vote in either house of Congress.

This type of “percolation-up” leadership launched Marcantonio to national prominence, subsequently extending even to international capitals. His spaghetti dinners for Congressmen of all political stripes were exercises in legislative collegiality such that then-Representative Richard Nixon – Republican of California – might cede him time on the House floor to go on the record about his radical policy positions in America’s interest.

The unlikely pair collaborated again in 1950 in undoing Democratic Representative Helen Gahagan Douglas, who was contesting Nixon for a United States Senate seat in California. Marcantonio saw the one-time Hollywood actress as exemplifying liberalism’s compromise with McCarthyism. Marcantonio allowed himself to be a political straw man, discreetly giving Nixon the okay to compare Douglas’ voting record to his own, tainting her with his far-left reputation through what became known as the infamous “Pink Sheet,” which reached a half-million California households.

Meyer noted that such a strategy reflected, again, the national reputation as a spokesman for the American Left over the 14 years he served in the House of Representatives between 1934 and 1950. Meyer consistently and continually poses the rhetorical question in his presentations about the East Harlem Representative: “Why would a comparison to Congressman Marcantonio’s voting record matter to anyone on the West Coast unless they were fully aware of him as a consequential political figure.”

The Rise of Frank Sinatra as Entertainer and Progressive Leader

Meyer’s presentation addressed the artistic rise of Frank Sinatra and his contribution to the progressive movement, along with the support and direction provided by his mother.

Natalie “Dolly” (Garaventa) Sinatra, hailed from a town near Genoa. She lived with her husband and son in Hoboken, New Jersey’s Little Italy, and was able to obtain employment as one of the few Italian Americans in the aforementioned Hague machine in Jersey City.

Her tasks were to register and canvas Italian American voters, and coordinate communication among residents by translating from one Italian dialect to another. Dolly Sinatra became a Godmother figure, politically and spiritually, and was asked by many neighborhood parents to stand in for the Baptism of their children.

Meyer invoked the adage: “The favorite son of the mother is the one who becomes famous.” As the only child, Sinatra received the best his mother had to offer. With Hoboken across the Hudson River from midtown Manhattan, Sinatra would take the ferry into the city and perform at Jazz Clubs sprinkled around the West 50s streets. This represented bold behavior as people in Hoboken’s insular Italian community did not typically traverse its border. When Sinatra and his first wife moved to Jersey City – right next door to Hoboken – it was for only the sixth time in her life she had stepped foot in that city.

Having learned politics in his mother’s kitchen, Sinatra was bound to become a progressive fighter, first in his support for Franklin Roosevelt’s presidency. Famously, he became involved in fostering harmonious relations between different races and ethnicities. He developed, too, Meyer pointed out, an association with the communists of his day and appealed to Americans, through his crooner’s craft, to confront racism, to unite against Fascism and Nazism, and to challenge his young audience to refrain from violence.

He would star in a film, The House I Live In, and sing a song of the same name, wherein he prevents some street kids from picking on a youngster different than them with a lecture about tolerance and mutual respect. (The song’s production preceded the film, which won an honorary Academy Award in 1946.)

Life imitated art when a racial incident at Benjamin Franklin High School prompted Covello, Rep. Marcantonio and Mayor La Guardia to enlist Sinatra in singing to, and speaking with, an auditorium full of students on racial harmony. The result was the site of Italian American, African American and Puerto Ricans marching arm-in-arm during the Columbus Day Parade.

When the Hollywood Ten were indicted in 1947 and then sent to jail for remaining tight-lipped, Marcantonio stepped into the House well on their behalf. Sinatra did, too, Meyer stated. Like Marcantonio, he would also support the Progressive Party presidential bid of Henry Wallace in 1948, which sought to make reality the candidate’s vision of the 20th century as the “Century of the Common Man.” (Wallace’s candidacy failed, but was, as Dr. Meyer points out, especially set back by the untimely death of Fiorello La Guardia the year before, who would otherwise have been his Vice Presidential running mate.)

Sinatra was willing to risk career status. He, Paul Robeson, Dalton Trumbo, and in a later generation, Bobby Darin, took stands that resulted in setbacks to both their prestige and finances. This is in stark contrast to today’s “New-New Left” who not only risk little from adopting controversial positions, but stand to gain social media followers, political cachet, and commercial sponsorship.

Sinatra, Meyer recalled, was denied a passport when he wanted to sing for American troops in Korea thanks to the complicit and coordinated opposition of suspecting civic organizations, a paranoid political establishment, a prying press, and a broader media sowing an atmosphere of mistrust.. Newspapers insinuated his communist, or mafia ties, and frowned upon the divorce with his first wife to be with Ava Gardner.

Isolated and ostracized, Sinatra realized the amount of energy required to defend one’s self can exhaust, stagnate, or destroy a life. Sinatra eventually broke away from any conspicuous involvement with the Left movement, while remaining progressive. He never “named names” during McCarthy’s anti-communist witch hunts, discreetly continuing to give money to blacklisted performers, and remaining active in the Civil Rights Movement.

“Sinatra was young enough to start over,” Meyer noted. “At his age, you could still pick up the pieces.”

As Sen. John F. Kennedy’s star rose in the late 1950s, he and Sinatra palled around. However, Robert Kennedy eventually advised his brother to stop hanging out with Sinatra because of the crooner’s friendliness with mobsters.

A PBS documentary on Italian American for which Meyer was interviewed, recalled how Kennedy had planned on visiting Sinatra at his home where the singer had a heliport built especially for the occasion. In lieu of a visit with Sinatra, Kennedy tactlessly canceled his trip, and then, adding insult to injury, unwisely chose to spend the weekend with the cleaner crooner, Bing Crosby.

It must be emphasized how in this day and age, such a decision to blatantly replace and plainly substitute one person with another rather than generically cancel based on an unanticipated scheduling conflict is considered a “rookie mistake”– especially in light of Crosby’s checkered history of committing domestic abuse. This error in judgment would have consequences.

Needless to say, between that incident and the top-down, elitist notion of the “Best and the Brightest” promoted by the Kennedy administration – in contrast to the bottom-up, grassroots nature of progressive government during the Roosevelt years – Sinatra felt double-crossed by, and alienated from, Kennedy and the Democratic Party. He eventually became a Reagan Republican, while continuing his contributions to progressive causes such as the NAACP.

Conclusion

In more contemporary times, there is a misplaced concern and/or an obliviousness as to exactly what is the adverse impact of the continued stereotyping of Italian Americans by the media and in the entertainment industry.

For example, a non-Italian prospective spouse does not “football huddle” with their parents to speculate on whether the potential Italian marital partner has ties to organized crime. Italian Americans are not encountering the kind of discrimination that Mario Cuomo did when being rejected by a white-shoe law firm, or when he encountered obstacles in his near-run for the presidency.

However, the portrayal of Italian Americans as uncouth political reactionaries detracts from the consideration of whether the history of the Italian American progressive tradition offers relevant insights that can address contemporary problems in leadership, school learning strategies, bilingual education, race/ethnic relations, organizational management, and leadership with integrity.

His New Haven lecture, along with his book about Marcantonio, and countless articles and lectures, elevates Dr. Meyer to the status of eminence gris (and honorary Italian) with respect to scholarship on this underrepresented aspect of the Italian American legacy.

This tradition, and its Old Left context, can provide constructive lessons to a disoriented “New New Left” and an American mainstream that might be shockingly pleased to learn its value.