Marianna Randazzo, author of “Given Away, A Sicilian Upbringing” wrote for our magazine this touching and well-documented article, based on the true events that occurred on August 8, 1956 at the Boiz du Cazier Coal Mine in Belgium. Interviews were conducted by her with the relatives and friends of those affected by the tragedy in Charleroi, Belgium.

On August 8, 1956, eight-year-old Sarina DiMartino, her ten siblings and parents lived in the town of Charleroi, in Belgium. It began as an ordinary day in the DiMartino household. As ordinary as any day could be with one father supporting a family of eleven children and one mother attending to all the chores, responsibilities and obligations of the home, children and husband.

Belgium was not their native home. Some of the children had still not mastered the French language that was spoken in school in and in the town. Like the wave of immigrants that had once occupied the Little Italys of America, this massive family found comfort and solitude among themselves and others like them. It was clear that they did not fit it: they were Italian.

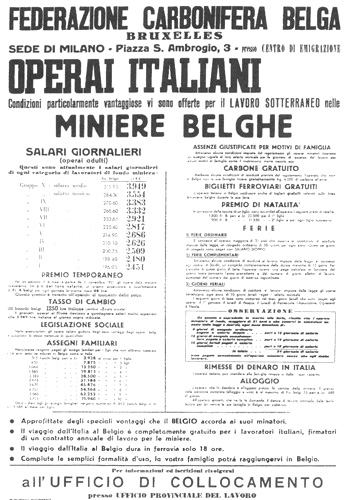

In Sicily, unemployment was in an unbroken upsurge. Sicily and the rest of Southern Italy, the Mezzogiorno as it came to be known, had always been poorer than the rest of the peninsula. Despite’s Italy’s unification in 1861, the problems that existed were left unsolved and almost unchallenged for a hundred years. The number of unemployed people was estimated to be about two million, and probably another two million were underemployed. The postwar years were brutal for Sicilian families, especially families as large as the DiMartinos.

“That was the reason my father brought us to Belgium,” explains Sarina, “Employment. Opportunity. Italians were told, ‘Go to Belgium, it’s good’. My father did not know better,” she sighs with sadness. “Italians were desperate for work, we were so many children.”

After World War II, Europe had the arduous task of rebuilding itself. In Italy work was minimal, food scarce. Coal reigned supreme in Belgium. During World War II, after the German invasion, Russian POW’s were used by the Nazis to work the Belgian mines. Most Belgians did not want backbreaking, filthy jobs such as mining, and a shortage of manpower had ensued. Free train tickets, promises of lodging, and a pact of free coal for Italy lured Italians to Belgium’s mines.

“That morning, August 8th, we knew something was wrong. Papa had not yet left for his mining job at the colliery. He gathered six of the oldest children around the table where a loaf of bread was placed. It was not sliced. He carved a large cross into the bread and made us pray. He told us something terrible had happened to the men in Marcinelle. He started crying, sobbing, and weeping. His grief frightened us terribly. We had never seen our father sob. Many of those men were his friends, some from our hometown in Sicily.” Sarina wipes the tear from her eye. Then she starts recalling the names of those men, and with each man’s name came a brief comment about their children or their mothers, or she recalled the color of their hair or eyes…”Some were just young boys,” she concluded.

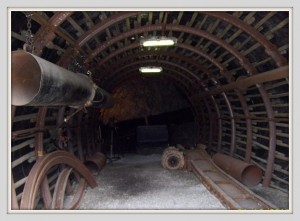

A mining wagon incorrectly positioned in the elevator cage struck an oil pipe and electrical cables when the elevators started moving, causing a fire. The men, Italians, Belgians, Polish and Greek miners were trapped. They were working 800 meters underground in the galleries. From an altitude of 835, a wagon sheared the wires that carried the current, plunging into the darkness. Fire and flames flared up quickly. Nobody could go back because the cages were locked as was the emergency elevator shaft. The sirens resonated and the pain and fury of the incident were felt miles away. It was excruciating to the families who knew their friends and loved ones were below.

“Do you know how many Italians died?” Sarina asks. “136, more than half the men were Italians,” she recounts as if the incident had happened yesterday and not 58 years ago.

“The Italians were mistreated. They did not want us here. They did not hide it. Do you know what they wrote above the signs in the bars and restaurants? NO DOGS, NO ITALIANS. Imagine seeing that? We were no better than the dogs? My father would tell us not to look at the signs. Yet, those were words we all understood.”

Italians had different customs, languages, and a lack of training in mining compared with the miners that preceded them. Discrimination awaited them despite the pact Belgium made with Italy to lure mine workers.

At Marcinelle, Italians were living in tin shacks; the same used by the Nazis as a labor camp and then by the Allies as a POW camp. They did not all have running water. The Belgians did not like the poor and noisy Italians. They lived in the shacks because they were not wanted.

The real estate ads in all carried the same note:

“Pas d’Etrangers, pas d’enfants, and pas de bêtes.” No foreigners, no kids, no pets.

It was documented that between 1946 and 1956, over 740 had died in mining accidents.

“Had it not been for other Italians like us, our family would not have housing. Italians helped each other,” she recalls. “It was all we had.”

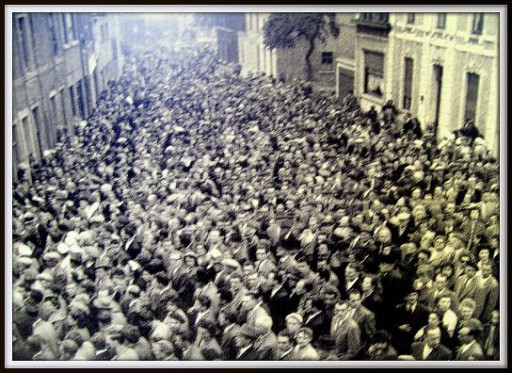

“My parents did not allow us to attend the funerals, everyday they visited the homes of the families waiting for the dead. Everyone suffered for Marcinelle. There were Sicilians like us,” she recalls. “The whole town and soon the whole world was in an uproar, it was on the television set, people in Italy began to hear about it. They knew, they knew,” she continues weeping softly, “That the miners trapped at the bottom, would never see the light of day again.”

“We left Italy for the “coal pact”. For years, my mother regretted leaving Italy. My father had the last word on the matter.” She continues with an expression that tells me that’s just the way it was.

The television kept showing the desperate families pressing against the gates, hoping and praying that the rescuers would pull out miners breathing from the rubble. My father went every day, he would not take us,” Sarina recalls. “Not even my brothers whom had they been a year or two older might’ve been buried in the rubble as well. Thank God. Thank God!” she clasps her hands and looks up at the heavens.

After 15 days of rescue operations, the final verdict came: “Tutti cadaveri!” All corpses.

The Marcinelle Museum, tell of miners feeling so close to death they pinned names on themselves in the hopes of being recognized, brothers dying together, hand in hand and a miner’s notebook recording the atrocious circumstances of those final hours: “I did everything to get out of this hell. However, the Gas comes from everywhere. I begin to choke. My comrades have already fallen to the ground, it is eight and ten. I feel that I am dying.”

Recognizing the bodies was impossible even to the rescue workers that worked with them every day. The victim’s faces were blackened, bloated and disfigured.

Recognizing the bodies was impossible even to the rescue workers that worked with them every day. The victim’s faces were blackened, bloated and disfigured.

“Tutti Cadaveri,” Sarina recalls, “The whole world was watching and crying. In Italy, they knew how difficult it had been for their husbands, brothers and sons. They knew that Italy had sold us out for a piece of coal.”

In today’s Belgium, Italians believe it was a disaster that could have been avoided. Miners were treated like slaves, in unsanitary and unsafe conditions, for low pay. Each man who went into the tunnels was well aware of the mining disasters that had claimed the lives of so many before them. The promise of steady work, however, kept the workers coming.

Sarina’s mother-in-law, 92 years old Signora Saietta, is one of the few survivors who worked in the Marcinelle mines in those days.

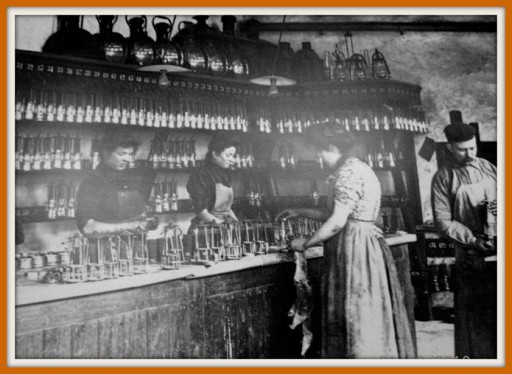

“It was not clean,” she recalls the unsanitary conditions. “There was a “hanging room” where the men changed from their work clothes to their home clothes. They paid the few francs to take a shower, but the soot and the sweat and grime, still clung to their bodies. I know my husband was one of them. He worked in the mines, 12, 14 hours a day when he was young. Then it slowed down to 8 hours. My job was to clean the clothes but they only cleaned them about one time a week. In the morning, the poor souls had to put on filthy clothes. They were filthy before they even began.

The mine was reopened after the disaster. We went back to work after the tragedy. We needed jobs,” she shares with me a photo of her husband in the mine. I did not have the heart to ask her for a copy.

“So many Christians [that is how Sicilians call people] died that day, I never allowed my sons to work in the mines; it was too dangerous. After, it was like a graveyard. I cried every day, but what could I do, I needed the job.” Tears still flow freely from the old woman’s eyes. “The horses were better treated. They were considered more productive than the miners were. If you didn’t come back to work, you could easily be replaced.”

The Le Bois DuCazier Museum has a cemetery-like character to it. The mine was restored and converted into a museum in 2002. The colliers were not men; they were a number assigned to them on a small medallion. They exchanged the number for a lantern as they descended into the mines. When a miner quit or expired, the medallion was given to a new miner. Numbers did not have to be erased like a name.

I walked through the Le Bois DuCazier Coalmines, which have since fallen silent, with Sarina DiMartino, the little girl who was eight years old on that fateful day. The site is like a graveyard; garland and flowers everywhere.

You can hear the echo of the pain and sorrow reflected in the photographs on the walls, and in the hearts of families like the Di Martinos.

As an Italian, a daughter, a part of history, she will always take it personally. “They were treated no better than dogs.” For Sarina and her family, the story is never over.

The tragedy marked the end of the arms trade / carbon between Italy and Belgium. In the resulting prosecution, the trial court acquitted all of the accused on October 1, 1959.

The life stories of the coal miners are the last expressions of an era lived in suffering, without any pretentious heroism. Their sacrifice is one of the darkest pages in the history of Italian emigration.