The New York Times has published a series of articles and essays collectively entitled the “1619 Project,” promoting the jaundiced perspective that American history was not founded on good, true, immutable principles, but on the evils of slavery, bigotry and oppression, which have poisoned every aspect of American society and culture such that all of America’s problems — including, the series posits, traffic patterns — stem from these historic injustices. The 1619 project posits that American history did not begin in 1776, but with the arrival of the first African slaves in the American colonies in 1619.

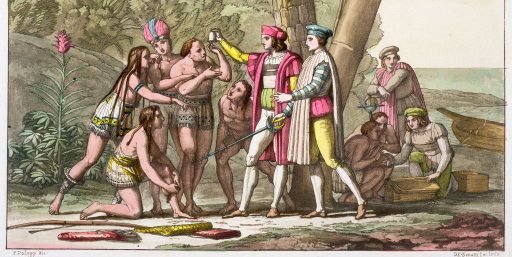

I propose that one should go back even further. Perhaps we can call this series of articles on Christopher Columbus the “1492 Project” to demonstrate that Columbus’s landfall in the North American Caribbean was really the beginning of the Americas and the establishment of Western Culture in these continents. My “1492 Project” posits that Columbus’s peaceful and amicable first contact with over a dozen tribes in the West Indies on his First Voyage, and his freeing of scores of Taino slaves from Carib captors on his Second Voyage (a civil rights activism that continued, as future articles will demonstrate, on both his remaining voyages) established the Americas as a bastion of goodness from which has sprung the United States, the freest, most-tolerant, most-successful and wealthiest heterogeneous society in the history of the earth.

My “1492 Project” counterpoint to the “1619 Project” polemic is important because getting our history straight is important. Unlike other countries, Americans are not united by skin color, race, ethnicity, language or religion. As President Abraham Lincoln said in his Gettysburg Address, “We are a people conceived in liberty and dedicated to the proposition that all Men are created equal.” Princeton University Professor and Fellow in American Studies Allen C. Guelzo notes that because we are a people united by a principle that is taught to us by our history, we must preserve rather than spoil or despoil that history. As Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn wrote, in his three-volume book Gulag Archipelago, about his years suffering in a Soviet gulag, “The first step a tyrant takes toward enslaving a people is to steal their history, for in that case, no one has anything from the past with which to compare the present, and any horror can be normalized.” To that end, I bring you my next installment in preserving the history of Christopher Columbus, who, in turn, fought tirelessly and to the end against the tyranny of the Spanish hidalgos, and to preserve the peaceful tribal peoples of the West Indies.

My last article for

L’Idea Magazine, published on Columbus Day weekend, detailed his first trans-Atlantic voyage; his discovery of the Americas (in the sense of bringing them to light to the rest of the world); and his successful and peaceful first-contact with every single tribe he encountered, including the warlike Caribs who attacked him on sight but whom he still managed to conciliate. This article resumes with Christopher Columbus’s return to Spain with his willing islander passengers and tells the remarkable story of Admiral Columbus’s continued efforts as the first civil rights activist of the Americas, including his life-saving “Underground Railroad” — or perhaps, more aptly, “Underwater Railroad” — by which he sailed from island to island rescuing many Tainos from their man-eating captors.

While moored off the island of Hispaniola (now Haiti and the Dominican Republic) during his first sojourn in the West Indies, a ship’s boy took control of the Santa María‘s wheel against Admiral Columbus’s orders and damaged the flagship so badly on rocks that it was rendered unseaworthy. Columbus also wished to take a cadre of not only willing but eager islanders back to Spain to meet the King and Queen. In order to do so with only the two small, remaining caravels, he left behind thirty-seven sailors to create the first Spanish settlement, Navidad — “Christmas,” named after the day in 1492 that it was founded. He left the settlers with strict orders not to trouble the islanders and left his discipline officer, Diego de Araña de Córdoba, and the Crown’s steward, Pedro Gutiérrez, behind to ensure that they behaved.

He did bring the eager islanders back to meet the Spanish Crown, but first landed at the Canary Island way-station, under the control of Portugal’s King John, and then in Lisbon itself. King John welcomed Columbus with “trumpets, fifes and drums and with a grand escort” (Hernando Colón, Life of the Admiral, Chapter 41), having relinquished his grudge against the Genoan sailor for turning his back on Portugal and taking his business to Spain. King John did so not because the King’s own treachery had prompted Columbus to cease business with Portugal — he had delivered Columbus’s maps and charts to his own private flotilla and sent them away without Columbus, a deceit Columbus discovered only when the Portuguese flotilla limped back to port crippled by a storm. Rather, King John and his Portuguese subjects — and indeed all of the world — saw Admiral Columbus’s feat as more than merely a victory for Spain, but a human achievement.

Similarly, upon Admiral Columbus’s return to Spain all of Castle “flooded from all directions to see him; the roads swelled with throngs come to welcome him in the towns through which he passed” (Bartolomé de las Casas, Historia de las Indias, Book I, Chapter 78). The monarchs received him with great anticipation and Admiral Columbus “praised” the Tainos to the King and Queen. He urged the monarchs that the islanders were “ready to receive the faith” (id.). Indeed, the Taino passengers willingly and gratefully received Baptism, rendering them immune from enslavement by any who would seek to apply the repartamiento to the tribal people of the West Indies, that part of the feudal “encomienda” system that entitled medieval Spanish nobles to subject conquered enemies to servitude.

Admiral Columbus rode in a parade with the monarchs through the streets of Castile, sitting in the seat next to the King that had been previously reserved for the young Prince John. Even as they rode, the King and Queen discussed launching the second expedition, and the contract for it was drafted and signed immediately.

Admiral Columbus embarked on his Second Voyage from the port of Cadiz on September 25, 1493, now fitted with a fleet of seventeen ships, manned by sailors and “hidalgos,” low, landed nobles. After another stop at the Canary Islands way-station, his fleet completed the remainder of the crossing in less than twenty days, arriving on the first Sunday after All Saints Day.

The Admiral specifically went looking for the islands of the man-eating Caribs, of whom the Tainos constantly complained to Columbus. Dr. Diego Chanca, one of the surgeons of the fleet, wrote in his epistolary account of the Second Voyage, “By the goodness of God, and thanks to the Admiral’s skill and knowledge, we had reached them as directly as if we had been following a known and familiar course.”

On the first inhabited island, Guadalupe, the landing party found a small Taino boy and a group of Taino women whom the Caribs had kidnapped. In the Carib huts, left unoccupied while the Caribs went marauding, the landing party found “great numbers of human bones and skulls” used as “hanging vessels.” Through the Taino translator that had returned to the West Indies with the fleet, the women explained that the Caribs “made war against the neighboring islands” by “raids in their canoes,” shooting serrated arrows tipped with poison. Chanca noted that the Caribs “raid the other islands and carry off all the women they can take, especially the young and beautiful, whom they keep as servants and concubines.” The Caribs “had carried off so many that in fifty houses we found no males and more than twenty of the captives were girls.” Chanca wrote, “These women say they are all treated [by their Carib captors] with a cruelty that seems incredible”: the Caribs murdered and ate the Taino men, raped and impregnated the Taino women, castrated and enslaved Taino boys (whom they later ate when they reached adulthood), and ate not only the remaining Taino children they captured but also the infants to whom the raped sex slaves give birth.

The crew found corroborating physical evidence of cannibalism in the huts of the Caribs. In one hut, “the neck of a man was found cooking in a pot.” In another, they found “human bones” that “were so gnawed that no flesh was left on them except what was too tough to be eaten” by a human (Letter of Dr. Diego Chanca). In yet another Carib hut on Guadalupe, they found “a human arm [that was] cooking in a stewpot” (Hernando Colón,

Life of the Admiral, Chapter 63). Indeed, if any doubt remained, the Caribs would themselves go on explicitly to confirm that they were cannibals. Dr. Chanca wrote of the Caribs, “They say that human flesh is so good that there is nothing like it in the world” (Letter of Dr. Diego Chanca).

But before any parleys with the Caribs occurred on this voyage, the Admiral’s fleet sailed from island to island, passing one that the Taino women from Guadalupe explained: “was uninhabited, because the Caribs had removed the entire population.” At every landfall, Admiral Columbus liberated Tainos from the Carib villages, many of which were found empty upon arrival, and many others of which were abandoned by the Caribs upon seeing the landing party approach. Island by island, groups of liberated Taino women and children fled “of their own accord” into the protective aegis of Admiral Christopher Columbus (id.). As the fleet was rescuing women and boys from the Carib island of San Martino, a canoe full of both male and female Carib archers returned, and opened fire on the landing party, wounding many and killing one Basque sailor. Although the penalty for such a murder was death, Columbus spared the lives of the captured Caribs, whom he ensured would have their day in court before the Spanish Crown.

Though the hidalgos — noble-born and ex-con alike — wanted to force the Tainos to build the settlement for them, Governor Columbus would not permit the use of the labor of the islanders.

The Admiral continued to sail throughout the archipelago, visiting Boriquen (now Puerto Rico), Hispaniola and hundreds of other islands and islets, recording the flora and fauna of each. Once the fleet safely reached Taino lands that the Caribs had not taken over or emptied, Admiral Columbus “put ashore” those of the liberated Tainos who wished to return home, now well-fed and provisioned with clothes and other gifts (id.). Before long, Admiral Columbus rescued no less than ten women and an unknown quantity of children and adult, male survivors. Long before Harriet Tubman and Levi Coffin helped African-American slaves escape via the “Underground Railroad” of the United States, Christopher Columbus conducted the first North American Underground Railroad in the Caribbean, freeing Taino slaves from their Carib captors.

But Admiral Columbus could not neglect the nearly forty sailors he had left behind on Hispaniola to found the settlement of Navidad. After freeing the Taino slaves, Christopher Columbus made his way in search of the settlement. The Tainos of Hispaniola flooded the beach and wanted to board the Admiral’s ships. Admiral Columbus “kindly received” those he could, but was focused on locating his forty men left behind. A cousin of Guacanagarí, the cacique (chieftain) that Admiral Columbus had made fast friends with on the First Voyage, brought the Admiral dire news: the Carib high-king Caonabo and a lesser king, Mayreni, had attacked and burned Navidad and Guacanagarí’s village, had wounded Guacanagarí, and had murdered all of the Spanish settlers in cold blood (Hernando Colón, The Life of the Admiral, Chapters 63-64; Letter of Dr. Diego Chanca).

The next morning, Admiral Columbus went to Navidad, and found the observation shelter “burnt, and the village demolished by fire.” He visited Guacanagarí and found him convalescing from a painful leg injury inflicted by one of the Caribs’ stone weapons. The islanders of Hispaniola were still shaken up by the Carib slaughter. Some of the liberated Tainas who had remained on Columbus’s ships now left to join the diminished village at the urging of Guacanagari’s cousin. Their tribe would need to rebuild and would need women to do it (id.).

Three months later, Governor Columbus, as he had been titled by the Crown of Spain, began building a new settlement, named Isabela, after the Queen who was so fond of him. He and the crews of his seventeen ships constructed irrigation canals, mills, water wheels and farms with “many vegetables.” Taino caciques of many tribes and their womenfolk frequented the settlement bringing yams, “nourishing [and] greatly restor[ing]” the Spaniards, who were grateful for the succor (id.). But just as the Europeans had brought diseases to which the islanders of the West Indies had built no immunity (all of which have since been cured by modern science) so, too, did the settlers succumb to diseases transmitted to them by the Tainos (none of which have been cured by modern science, including syphilis). Also, because the Europeans were not accustomed to the tropical climate, the vegetables they grew rotted more quickly than they anticipated. For all of these reasons, as well as “from hard work and the rigors of the voyage” (id.), the Spaniards fell deathly sick at Isabela.

Though he contracted no known diseases from the Tainos, Governor Columbus too fell sick from the rigors of the voyage, the settlement-building, and the differences in climate. Caciques of various Taino tribes sent villagers to help the settlers pan for gold, since they understood that the King and Queen who had sent the settlers required it as currency to make the undertaking possible. But many of the hidalgos plotted “to raise a revolt [and] load themselves with gold” as they were “exasperated” and “discontented” from “the labor of building the town” (Hernando Colón, Life of the Admiral, Chapter 51). Some of the hidalgos came from long lines of blue-blooded nobles, and had never toiled. But because so few hidalgos deigned to depart the comforts of Castile for the tropical frontier of the West Indies, the Crown hatched a hair-brained scheme to make up the difference: it pardoned convicted criminals — murderers, rapists, thieves and other ne’er-do-wells — and granted them noble titles if they agreed to help settle the Caribbean. Though the hidalgos — noble-born and ex-con alike — wanted to force the Tainos to build the settlement for them, Governor Columbus would not permit the use of the labor of the islanders.

Governor Columbus encountered “many Indian villages,” making friends wherever he went…

So began the discontent that would forever drive a wedge between the entitled, Spanish

hidalgos and their low-born, foreigner governor. “They had been plotting in secret to renounce the Admiral’s authority [by] taking the remaining ships to return in them to Castile” (

id.). Beginning a tactic that would persist to this day, the fleet’s accountant, Bernalde Pisa, instigated the plot by writing libelous falsehoods about Governor Columbus to be delivered to the Crown. Despite this heinous act of mutiny by Pisa, Christopher Columbus nevertheless demonstrated himself to be the “kind” and “good-natured” man of mercy de las Casas described him as in his

Historia de las Indias (Book I, Chapter 3); when he discovered Pisa’s libelous correspondences, out of deference to King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella, Governor Columbus “punished [Pisa] only by imprisoning him in the ship, intending to return him to Castile with a list of his crimes” (Hernando Colón,

Life of the Admiral, Chapter 51).

Now restored to health, but still distressed about the Carib menace that destroyed the Navidad settlement and threatened the Taino tribes, Columbus left the under-construction Isabela settlement and traveled to Cibao, near the northwest corner of Hispaniola. There, he built a protective fort, Santo Tomás, “with which to keep that country at peace” from Carib marauders and Spanish gold-mongers (id.). In this endeavor, Governor Columbus encountered “many Indian villages,” making friends wherever he went (id., Chapter 52). Governor Columbus stationed Captain Pedro Margarit and a few men-at-arms at the completed fort to protect the area from High-king Caonabo’s Carib marauders, and returned to Isabela (id., Chapter 53).

In Columbus’s absence from Fort Santo Tomás, a tribe of islanders robbed Margarit and his men. Margarit captured the robbers and cut off their ears in retaliation. He then brought them to Isabella, before Governor Columbus, for further punishment, but Columbus was horrified by Margarit’s maiming of the islanders. Again, exhibiting the “good judgment” and “unusual insight into human and divine affairs” that de las Casas described of him (Historia de las Indias, Book I, Chapter 3), Governor Columbus used the same clever intrigue on the islanders’ chieftain as he often used on the King and Queen of Spain. He told the chieftain that the punishment for the robbers’ crime was death, though Governor Columbus had no intention of ever carrying out that threat. When the chieftain heard the pronouncement, he offered a tearful apology for his villagers’ misdeeds. Columbus immediately set the robbers free into the custody of their chieftain, and announced to Margarit that the matter was settled (id., Chapter 93).

…the Jamaican inhabitants attacked again, but the Admiral diffused the conflict with no fatalities. Thereafter, the inhabitants bartered peaceably and one begged to return to Spain with the fleet.

No sooner had Governor Columbus adeptly resolved the Margarit affair did horsemen arrive from Fort Santo Tomás, informing that islanders had surrounded it and attempted to kill its occupants. In Columbus’s absence from the fort and without his pacifying presence, the relationship of the settlers there and the nearby islanders soured terribly. De las Casas makes a point to note, “I would not dare blame the admiral’s intentions” for the discord, “for I knew him well, and I know his intentions were good” (id.). Indeed, Governor Columbus shed no blood over the incident. He sent cavaliers to make only a show of their “arms and horses” as to “instill fear” in the tribal warriors responsible for the siege (id.). The tactic successfully scared the warriors off with no fatalities, liberating the besieged Spaniards (Hernando Colón, Life of the Admiral, Chapter 53).

In the Spring, Admiral Columbus explored the coastline of Cuba, making friends with its inhabitants and gifting them glass beads, hawk bells and brass bells, and other offerings. The cacique of the province exhibited great interest in the Catholic Mass the priests conducted, “listen[ing] attentively” and “giv[ing] thanks to God” (id., Chapter 59).

The following month the Admiral arrived at Jamaica. Although the inhabitants attacked on sight, he retreated as a show of peace and good will. Nevertheless, the Jamaican inhabitants attacked again, but the Admiral diffused the conflict with no fatalities. Thereafter, the inhabitants bartered peaceably and one begged to return to Spain with the fleet. Admiral Columbus “ordered that he should be well treated,” and obliged the man’s request to travel with them. Throughout the entire Second Voyage, whenever the islanders sought to come aboard the ships of the fleet, Admiral Columbus “treated them very courteously” (id., Chapters 54-55).

Meanwhile, Captain Margarit left his post, hijacked one of the seventeen ships, and returned to Castile, leaving Fort Santo Tomás. The islanders, under the command of Chief Guatigana, attacked again the unsupervised fort, murdering ten settlers in cold blood and setting fire to a hospital containing forty patients. Hernando Colón notes that the tribal warriors “would have killed many more if the Admiral had not arrived in time to prevent them” (id., Chapter 61). His men-at-arms caught some of Guatigana’s murderous warriors, but again, Governor Columbus exhibited temperance; he did not presume to try, much less punish, the attackers, but rather delivered the prisoners to the Crown to have their day in court.

But again demonstrating that “unusual insight into human…affairs” of which de las Casas wrote, Governor Columbus investigated further into the Santo Tomás massacre. He discovered that the unsupervised settlers had “committ[ed] innumerable outrages for which they were mortally hated by their tribal neighbors.” These outrages brought consequences. “All the caciques and kings” of the region were pressed into a war band led by none other than the cannibal High-king himself, Caonabo, the scourge of the Caribbean. Caonabo even attempted to press Guacanagarí’s tribe into service, but Guacanagarí “remained friendly” to the settlers and refused to ally with the cannibal king (Hernando Colón, Life of the Admiral, Chapter 61). Thus, one of the cacique kings in Caonabo’s service murdered one of Guacanagarí’s womenfolk on the spot, and Caonabo himself kidnapped another (id.), no doubt to impregnate her and eat her baby as was the Caribs’ want.

Columbus had freed the Taino slaves, built the multiple settlements and defeated the Carib marauders, bringing peace and slowly restoring prosperity to the land…

Guacanagarí implored Columbus to rescue his kidnapped villager. Though outnumbered five-hundred to one, Columbus hatched a plan to merely frighten the war band into retreat with the ruckus of musket shots. It worked, for a time. Hernando Colón noted, the war band “fled like cowards in all directions,” but the confrontation was not without its fatalities. Nevertheless, when the men-at-arms returned to the Governor with their prisoners, High-King Caonabo was among them. Caonabo defiantly proclaimed that he had indeed ordered the murder of the forty settlers of Navidad, and boldly announced that he would do the same to the settlers of Isabela. In spite of all of this, Governor Columbus did not harm a hair on the cannibal king’s head. Rather, he sent him back to Spain to have his day in court before the Crown (id.).

By his careful suppression of the cannibal rebellion, Columbus proved that his skills in ship command translated well into governance, despite that he had never held any political office in the past. Thereafter, although the settlers still struggled with food scarcity and disease, “the Christians’ fortunes became extremely prosperous” and peace reigned supreme. “Indeed, the Indians would carry [Columbus] on their shoulders in the way they carry [men of] letters” for the Pax Columbiana he established, though the humble “Admiral attributed this peace to God’s providence” (id.). In gratitude and brotherhood, the Tainos led the settlers to their own copper mines and revealed to the settlers the locations of precious gemstones such as sapphires, ebony, and amber; spices such as incense, cinnamon, ginger and red pepper; and gums and woods such as cedar, brazil-wood and evergreen mulberry (id., Chapter 62).

Now that Columbus had freed the Taino slaves, built the multiple settlements and defeated the Carib marauders, bringing peace and slowly restoring prosperity to the land, he decided to return to Spain to give an account of the entire affair. He suspected that Bernalde Pisa was not the only beleaguered, entitled hidalgo writing false complaints about him, and that the absconder, Pedro Margarit, may well have delivered more libelous correspondences to the Crown from the shifty and shiftless hidalgos on the ship he had hijacked.

Admiral Columbus set sail for Spain in two of the remaining sixteen ships of the fleet in March of 1496. After yet another run-in with Carib marauders who attacked him off the coast of Guadalupe, he discovered an island bereft of menfolk, the women of which were skilled archers Columbus described as exceptionally “intelligent” and of great “strength and courage” whom the Caribs descended upon periodically, as the women described, “to lie with them” (

id., Chapter 63). Because these women identified as Caribs themselves, the marauders did not eat their babies, but took them to raise as warriors. “As soon as their children are able to stand and walk, they put a bow in their hands and teach them to shoot” (

id.). These, and a similar all-female tribe on the nearby island of Martinino, formed the basis for the legends of the Amazonians, named for the Greek war-maidens of legend. The name would later be applied to the entire biome of the rainforests of what is now Brazil and the surrounding nations.

Despite all the conflict Christopher Columbus had endured at the hands of the warmongering Caribs, he released Carib prisoners into the warrior-queen’s custody and gave her gifts as a token of good will. The chaste Admiral’s charms affected not only the queens and noblewomen of Europe, but this female cacique as well. She “agreed to go to Castile with her daughter” and so “willingly” traveled back to Spain with the fleet (id., Chapter 64).

On April 20, 1496, Admiral Columbus’s fleet disembarked for home. On the long journey, the sailors “were so near starvation that some of them wished to imitate the Caribs and eat the Indians they had aboard” or “throw the Indians overboard” to conserve rations, “which they would have done if the Admiral had not taken strict measures to prevent them. For he considered them as their kindred and fellow children of Christ and held that they should be no worse treated than anyone else” (id.). Once again, as his Second Voyage drew to a close, Christopher Columbus proved himself yet again to be the first civil rights activist of the Americas — not merely of the Tainos, but of the war-mongering, man-eating Caribs as well. That “unusual insight into human and divine affairs” of his led him to see all the islanders of the Caribbean as people and children of God, and he always treated them as such.

His safe return to Europe on June 9, 1496, demonstrated that his unusual insight was not limited only to human and divine affairs. “From that day onward he was held by the seamen to have great and heaven-sent knowledge of the art of navigation” (id.).

In next week’s article of my “1492 Project” series, “Christopher Columbus: the Greatest Hero of the Fifteenth and Sixteenth Centuries (as Revealed by the Primary Sources),” the Admiral’s Pax Columbiana is shattered by the man whose deeds have, of late, been falsely attributed to the good Admiral Columbus. The true terror of the West Indies arrives: the man known to the Jihadist invaders of Europe as their bane and conqueror; to the Spaniards as their war hero of the Reconquista, but to the innocent Tainos of the West Indies as the racist, rapist, maimer, murderer and genocidal maniac Francisco de Bobadilla! Don’t miss it as all Hell is unleashed next week at L’Idea Magazine!

Robert Petrone, Esq. is a civil rights author and attorney, and an expert on Christopher Columbus. This article first appeared on Philadelphia’s Broad + Liberty magazine.