by Laura DiLiberto Klinkon

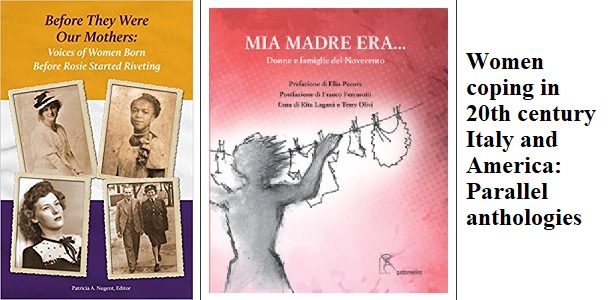

I recently discovered that an Italian friend living in Rome and an American friend from Rochester, New York have been involved with the publication in 2018 of two anthologies that are very similar in theme and approach. Both consist of reminiscences about the lives of 20th-century women, born from approximately 1894 to1939 as researched, remembered, and written by their daughters. Wondering how they compared, I found that except for their different languages, settings, and length, they are substantially similar, with chapters that are almost interchangeable.

Before they were our mothers contains 15 reminiscences of women who lived mostly in the United States, whereas Mia Madre Era… contains over 50 accounts about women living mainly in Italy; the Italian anthology is also characterized by a more thorough regional representation. In the American one, however, the women are of various ethnicities, two of them also Italian. Perhaps another notable difference is that the American accounts have a somewhat more political emphasis, whereas in the Italian there is a slightly greater emphasis on family relations, both nuclear and extended.

One could easily say that the books are the same, in that these accounts are written about mothers who experienced the difficult conditions of their time, and who dealt with them according to their various opportunities and capacities; the daughters’ writing about them, while naturally tending toward remembering them fondly, is nevertheless remarkably candid.

The great challenges faced by 20th century Italy, from the standpoint of two world wars and the continued Nazi presence even after the armistice, can be seen as understandably more severe than those of America, yet both countries had challenges in common, such as illness, unavailable medical facilities and know-how, death of loved ones due to both illness and wartime conscription, various types of prejudice (political, social, legal, and gender-based), limited opportunities for work and education, the discomforts and unpredictability of moving from one place to another, whether undertaken due to war-time compulsion, economic ambitions and opportunities, or desire for schooling.

The conditions reported in the two anthologies are different not so much in kind but in degree. To understand these differences, let us compare relatively similar situations.

Imagine an Italian family with four children and another one on the way, having to evacuate Albania, where the husband had been working peaceably for several years, to escape a Nazi invasion with their lives. And then imagine an Italian-American family who is told to move out of a parish-owned house by the priest in charge…because he “never liked [their] kind.” Both are harrowing situations, but certainly different in the intensity of the threat and response required.

Or compare a situation where a seven-year-old may stand at a window witnessing soldiers on the street fighting and killing one another, with reports of an Irish gang that repeatedly vandalize a newly installed traffic light because offended that the (Irish) green of the light is not positioned above the (British) red.

On a more intimate level, consider the difficulties that may arise with necessary cohabitation. A young American-Galician woman in her 20’s lives with her diabetic, overweight mother and her alcoholic, aging father; her imminent hope for relief, her boyfriend Mikael, whose duty he feels is to enlist to defend America abroad, is soon killed in action. Then consider two Italian mothers-in-law: one, a Contessa, with noble pretensions, the other a simple working woman who, dependent on their married off-springs’ economic and caregiving capabilities, are obliged to live together for years, challenged to live out their old age together peaceably.

Scarcity of food in cities, is, of course, especially rampant in wartime, and may require a Neapolitan father to go out to the country with his young daughter to gather the wheat remaining from the harvest even though the resulting flour from the grains collected is sufficient only for a few cookies. Then we see that a low-paid South Carolina farm worker’s right to bring home slightly more produce is a joyous boon for the family’s evening meal.

Scarcity of food in cities, is, of course, especially rampant in wartime, and may require a Neapolitan father to go out to the country with his young daughter to gather the wheat remaining from the harvest even though the resulting flour from the grains collected is sufficient only for a few cookies. Then we see that a low-paid South Carolina farm worker’s right to bring home slightly more produce is a joyous boon for the family’s evening meal.

We note that the disinclination to send children to school in Italy may have been due to help needed at home or distances that girls, especially, must not traverse alone, while a young Italian-American girl is kept in a school closet all day for retaliating unapologetically with punches against a bully’s ethnic insults.

One can see from these scenarios that there were onerous conditions in both countries, but relatively more intense or demoralizing in Italy. Yet the capacities the women draw upon are perhaps surprisingly the same: hard work, perseverance, determination, ingenuity, sometimes boldness or stoic reserve, sometimes a sense of accepting the reality of their condition, sometimes acknowledging the value of help.

A young Italian woman, pregnant out of wedlock and rejected by her family, gets a job as a farmhand and brings along her child, once born, in a wooden box normally used to cart produce; coincidentally in America, a child is being dragged to the field where her mother works in a cardboard box.

In Italy, where education and permission to work outside the home were traditionally limited, especially for poor women, many learned to sew, weave, or embroider, thus allowing them to create or enhance their own and their family’s income. In America, both education and jobs outside the home were more acceptable, but young women still often helped to sustain the family through housework and care of siblings while their own mothers went to work.

In Italy women who stemmed from more advantaged families, or who were more rebellious, managed to be educated and to be qualified as teachers or office workers. In one case, a young woman who was obliged to work in her father’s grocery store would regularly pilfer from the bankroll in order to finance off-hour training for office work. The same woman afterward faked an appointment with a government higher-up in Rome, so as to ask…and receive, his help in gaining better employment. In the American anthology, another woman, against her family’s wishes, enlisted in the army and then worked her way up to administrative positions.

Those who did have office jobs, in both countries, were subject to unwanted advances. In one Italian case, the harassing supervisor was fired; at the American Mayo Clinic, however, girls in the transcription pool simply had to do their best to avoid disrespectful touching.

These examples are intended to give eventual readers a glimpse of the 20th-century conditions and required moral resources of the women these anthologies record. As mentioned earlier, most of the accounts relate to the mothers’ praiseworthy conduct. None, on the other hand, can be said to be heroic in the usual sense of the word; some might even be said to be misguided.

In one instance, with the excuse that she was very sick and dying, an American mother accepted a marriage proposal on behalf of her highly educated daughter because she herself had a liking for the young man. In another case recorded in the American anthology, a mother of Russian ethnicity postponed her daughter’s schooling but insisted on her continuously practicing her violin to become a lucratively paid concert violinist who would make them rich. In Italy, one neurotic mother, who had given up her title of nobility by marrying a commoner, preferred to work all night at her sewing machine and sleep all day, thus avoiding her maternal responsibilities.

Mothers are both praised and castigated also for their reticence: castigated when they defer to their husbands without protesting a child’s harsh and unfair punishment, but praised when displaying stoic willingness to sacrifice their own comfort and well-being for the sake of others.

Both of these books offer insight into the condition of women and families during the twentieth century, one in English and relatively brief—which may be followed by a second volume in the future, the other in Italian, both more copious and regionally representative. They may be purchased as follows:

Before They Were Our Mothers: Voices of Women Born Before Rosie Started Riveting AMAZON online

Mia Madre Era…Donne e famiglie del Novecento

Sul sito dell’editore Gattomerlino, per il libro è disponibile anche la spedizione per gli Stati Uniti. Il libro si trova qui: Gattomerlino.it

Mia Madre Era…Donne e famiglie del Novecento e` anche possibile trovarlo sulle normali librerie online come queste:

https://www.ibs.it/mia-madre-era-donne-famiglie-libro-vari/e/9788866830856

https://www.lafeltrinelli.it/libri/mia-madre-era-donne-e/9788866830856