Interview by Tiziano Thomas Dossena

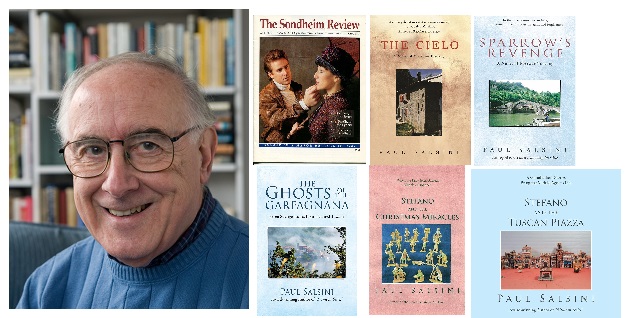

Paul Salsini is a multi-talented Italian American author who is a contributor to the upcoming second volume of A Feast of Narrative, an Anthology of Italian American Writers, which I edit. I thought that our readers would appreciate to know more about his wonderful books and very interesting life…

Paul Salsini is a multi-talented Italian American author who is a contributor to the upcoming second volume of A Feast of Narrative, an Anthology of Italian American Writers, which I edit. I thought that our readers would appreciate to know more about his wonderful books and very interesting life…

L’Idea: Paul, you spent 37 years as a journalist and 48 years as a college professor teaching Journalism and Musical Theater. Which one do you miss the most and why?

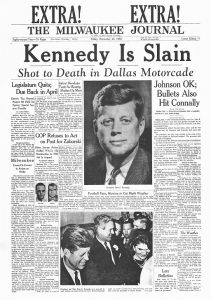

Paul Salsini: This may sound corny, but I knew in eighth grade that I wanted to be a journalist. I don’t know why, something about being on the scene but not being part of the scene, and also being able to write, which I loved to do. Not only that, but I wanted to work at The Milwaukee Journal. We lived in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan and got the paper and I read it religiously. So I was thrilled when I was hired by The Journal after I graduated in journalism from Marquette University in Milwaukee. Those were the glory days of the paper, big circulation, excellent staff, ground-breaking stories. I started as a suburban reporter, then joined the State Desk, became State Editor, responsible for coverage of the state and state government, and then my best job, Staff Development Director. I handled applications, did recruiting, worked with the staff, ran the intern program and, best of all, was the writing coach. I think I was one of the first writing coaches in the country. I worked with some of the best writers on the paper and it was a very satisfying job. Like other positions on newspapers, it no longer exists.

In 1970, I thought I’d like to teach and I landed an adjunct position at Marquette. Over the years, I think I taught almost every journalism course it offered. The best was the last, Narrative Nonfiction Journalism, which I invented. Students got to delve deep into subjects and write real stories.

In 1970, I thought I’d like to teach and I landed an adjunct position at Marquette. Over the years, I think I taught almost every journalism course it offered. The best was the last, Narrative Nonfiction Journalism, which I invented. Students got to delve deep into subjects and write real stories.

I’ve had a long interest in musical theater so when the instructor of History of the Musical Theater retired, I volunteered for that course. I developed a broad range, from vaudeville to “Hamilton.” It was a “core” course, which meant that all university students had to pick a course from a list. I guess mine looked like a “blow-off” course because it quickly filled to the room’s capacity – 60 students from all over campus. They soon discovered that there was work involved, but they loved it and I think they learned that art in any form should be a part of everyone’s life.

I don’t miss The Journal because journalism has changed so much and I know the staff is now depleted and has to do so much more than when I was there. I do miss my students from both departments and am still in contact with some of them. But I wouldn’t want to teach online; I’d miss the face-to-face relationships.

L’Idea: But you are still teaching, aren’t you?

L’Idea: But you are still teaching, aren’t you?

Paul Salsini: I’m not teaching anymore. The core curriculum was revised and, for unknown reasons, the course was dropped. But I still have a relationship with Marquette journalism. The college runs an online Neighborhood News Service that covers largely neglected areas of the city, and I do some editing of stories.

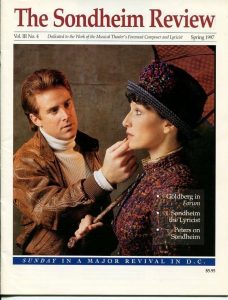

As I said, I’d long been interested in musical theater and enjoyed going to shows and reading about it. I have two favorite composers, Kurt Weill and Stephen Sondheim. In 1984, I thought, I’m a journalist and I like Sondheim, why not put out a publication devoted to his works? So I found a guy who would do the business side and I did the editorial side and we put out this quarterly magazine, The Sondheim Review/Devoted to the Work of the Foremost Musical Theater Composer/Lyricist. I did a lot of the writing. I traveled around the country (and even London) to write about shows and I interviewed many people, including Sondheim (who celebrated his 90th birthday in March 2020). But after ten years I needed to get a life so I gave it over to an assistant editor. It died a few years later. Over the years I had accumulated a large Sondheim collection of books, DVDs, CDs, tapes, articles, programs and other things. When my wife and I moved to a smaller apartment ten years ago I donated it all to the Marquette library, which established the Stephen Sondheim Collection, open to anyone.

I still teach, sort of. I give programs about musical theater, largely through videos, at retirement homes here. The people love them.

L’Idea: Although you were born in the USA, you seem to consider yourself somewhat a full-blood Tuscan, Why is it so?

Paul Salsini: My father was born in the small village of San Martino in Fredanna near Lucca in Tuscany. He came to the U.S. at 20, went to the Upper Peninsula of Michigan and became a copper miner. Other people from San Martino had arrived there earlier, and he boarded with a family that had five sons and a daughter. Yes, he and the daughter fell in love and married, my father and mother. So both sides of my family are from that same village in Tuscany and when I go to the cemetery there I see the Salsinis and the Consanis all together.

My mother made a lot of good Italian meals and my father and mother spoke Italian to each other, but not to us. I was always interested, though, and in 1985 The Journal sent me with a photographer to Italy for two weeks to write stories. That’s when I fell in love with Italy, and especially Tuscany. I think I wrote about 25 stories about the people, the issues, the history. The best part, though, was visiting my cousin Fosca, my father’s niece, who lived in the house where she was born in San Martino in Fredanna. She was just wonderful. She’s 95 now and still a hoot. Since her husband died two years ago she lives alone, does her own fabulous cooking and is beloved in the village. All of her siblings and all of mine have died, so we’re the last.

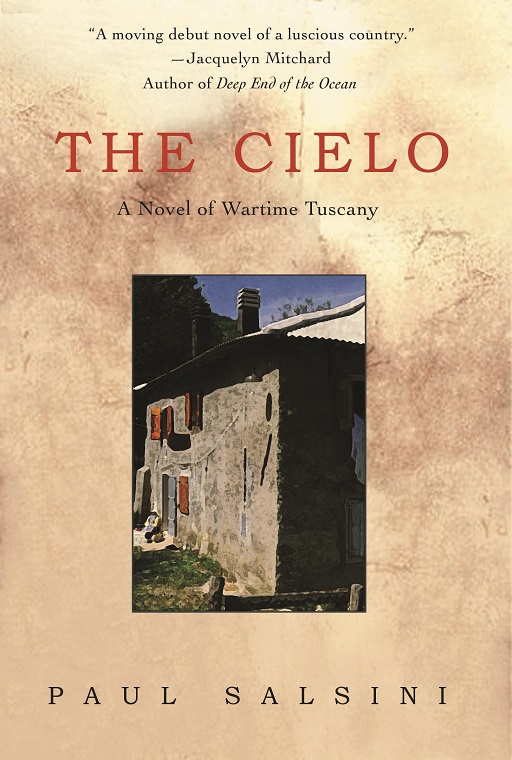

L’Idea: You wrote your first novel, “The Cielo: A Novel of Wartime Tuscany,” basing it on your cousin’s wartime experiences. Could you tell us more about that?

Paul Salsini: I have visited Fosca often, taking my wife and kids (we have three, and four grandchildren). One time, Fosca told us about living through World War II. She said she and neighbors from San Martino in Fredanna fled to the hills, literally, when the Nazis occupied the village. Some people stayed in barns, some in the woods and some in old farmhouses. She and her friends stayed in an abandoned farmhouse called the Celli, high in the hills that had been in the family for centuries. They remained there for three months, sometimes hearing nearby fighting between the Nazis and the partisans, until the Allied forces liberated the area.

Anyway, I was fascinated by her story and as a journalist I wanted to write it. But there were problems: I can’t speak or read Italian well, which was essential. I was working, so couldn’t spend months there. And many of the sources would be dead. So I decided to write it as fiction. I know, I know, journalists are often accused, falsely, of writing fiction, but this was different. So I spent months researching the war, the area, the partisans, the Nazis, etc. etc. It would be the story of how people were forced to live together while fighting was going on all around them. During the research I discovered that on August 12, 1944, Germans had invaded a nearby village, Sant’Anna di Stazzema, and slaughtered 560 people in four hours. It was the second-worst massacre by the Germans in Italy during the war. So that became part of the story, with a partisan assuming a major role, and the book becoming even more historical fiction.

So I finished the first novel I’d ever written and called it “The Cielo: A Novel of Wartime Tuscany.” I named the farmhouse Cielo, which means ‘heaven’ or ‘sky,’ but I also liked the way it was similar to the real farmhouse’s name, Celli. To my surprise, the book was well received and even won awards: First Place from the Council for Wisconsin Writers and First Place from the Midwest Independent Publishers Association.

L’Idea: From one novel about Tuscany, you end up with a series of six novels about that region. How did that happen and why are these novels all about the beautiful region of Tuscany?

L’Idea: From one novel about Tuscany, you end up with a series of six novels about that region. How did that happen and why are these novels all about the beautiful region of Tuscany?

Paul Salsini: Something strange happened after writing that book, and I’ve since learned that it happens to much more experienced writers as well. I couldn’t get those characters I’d created out of my head. They were real. I thought about them at night, wondering what they were doing. So I wrote a sequel, “Sparrow’s Revenge: A Novel of Postwar Tuscany.” It was about how that partisan, filled with guilt because he didn’t save his lover in Sant’Anna, sought revenge.

After that, yes, those people were still in my head and I couldn’t get rid of them. So I wrote “Dino’s Story: A Novel of 1960s Tuscany.” It was sort of a coming-of-age story about a boy who was born at the end of the first book and ten years old in the second and who goes to Florence to study art in the third. He’s there during the devastating flood of Florence in 1966. More historical fiction.

I called those three books “A Tuscan Trilogy,” but that was a mistake because those people were, yes, still in my head and I realized I was writing about them from decade to decade.

So I continued writing about these people in interrelated short stories. The first was “The Temptation of Father Lorenzo: Ten Stories of 1970s Tuscany” and then “A Piazza for Sant’Antonio: Five Novellas of 1980s Tuscany” and finally “The Fearless Flag Thrower of Lucca: Nine Stories of 1990s Tuscany.” All of the stories are set in the fictional Sant’Antonio, not unlike San Martino in Fredanna, and in Florence. The original characters age (some die) and some new ones arrive.

So I continued writing about these people in interrelated short stories. The first was “The Temptation of Father Lorenzo: Ten Stories of 1970s Tuscany” and then “A Piazza for Sant’Antonio: Five Novellas of 1980s Tuscany” and finally “The Fearless Flag Thrower of Lucca: Nine Stories of 1990s Tuscany.” All of the stories are set in the fictional Sant’Antonio, not unlike San Martino in Fredanna, and in Florence. The original characters age (some die) and some new ones arrive.

I decided that was the last of the series. Ezio the partisan and other original characters were now in their 80s and another book would have been very sad. I had to move on. But, yes, sometimes they’re still in my head. I wonder how Ezio and Donna, who live in the Cielo in the hills, are doing; I imagine that Dino’s adopted son from Albania must be in college by now, and I can only speculate on what’s going on between the handsome television priest Father Giancarlo and the former nun Anna.

L’Idea: I stand corrected: you wrote seven books about Tuscany, including “The Ghosts of the Garfagnana: Seven Strange Stories from Haunted Tuscany.” What’s different about this book from the others?

L’Idea: I stand corrected: you wrote seven books about Tuscany, including “The Ghosts of the Garfagnana: Seven Strange Stories from Haunted Tuscany.” What’s different about this book from the others?

Paul Salsini: After I’d completed the series, I thought about what to write next. I’d been fascinated by the Garfagnana area of Tuscany ever since, researching “Sparrow’s Revenge,” my driver/translator showed me the “Devil’s Bridge” near Borgo e Mozzano and told me the story of how the devil built the bridge in the Middle Ages. Surely, I thought, if a region can foster such a legend it must have lots of other good stories, too. (I’ve since learned that there are nine devil’s bridges in Italy alone and maybe up to two dozen in Europe.)

The Garfagnana, which is north of Lucca, is unlike any other area I’ve seen in Italy, not that I’ve seen all of Italy. It’s very rugged, with high snow-capped mountains, tiny villages, lots of green stretches. Just the kind of territory where witches and ghosts and strange traditions would occur.

So I fashioned a collection of short stories, interrelated again, about the people and places, and all with supernatural connections. It was fun.

L’Idea: You also wrote a nonfiction book, “Second Start.” What is this book about?

L’Idea: You also wrote a nonfiction book, “Second Start.” What is this book about?

Paul Salsini: When I was at The Milwaukee Journal I wrote an article for the paper’s Sunday magazine about “second-career” priests. These were men who had gone through a seminary near Milwaukee that specialized in training and ordaining men who had had other careers. As far as I knew, this hadn’t been written about, so I expanded the piece into a book and included priests from other areas of the country, including New York.

Their stories were inspiring and the book was well received. I wish I knew what happened to the priests. I know a few have died, and I’ve heard bad things about one of them. That’s to be expected, I guess.

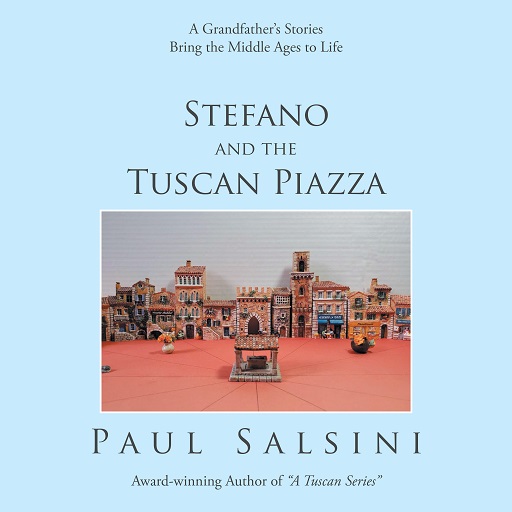

L’Idea: You are the author of “Stefano and the Christmas Miracles” and “Stefano and the Tuscan Piazza,” two children’s books. What inspired you to write for children? What kind of message these two books are trying to convey to the readers?

L’Idea: You are the author of “Stefano and the Christmas Miracles” and “Stefano and the Tuscan Piazza,” two children’s books. What inspired you to write for children? What kind of message these two books are trying to convey to the readers?

Paul Salsini: I have a presepio that I bring out every Christmas. It started with a few pieces I bought in Florence and I’ve been adding one every year so there are now more than forty figures around the stable—and no more room! They’re made by Fontanini. I’d always wondered about those “other people” who are in it – a woman with geese, a man sharpening a knife, a boy asleep, an old man guided by a boy. Why are they in the Nativity scene?

So I wrote a story about a grandfather, “Nonno,” telling the boy Stefano stories of some of them. In each case, the person goes to Bethlehem and there is a miracle at the manger. For example, a boy who is a terrible bugler but is part of a “boy band” goes to the stable and suddenly is able to play beautifully.

The second book, sort of a sequel, also resulted from a collection begun in Florence. Arranged on a bookshelf in our living room are miniature ceramic pieces that form a Tuscan piazza, a tower, a church, a palace, houses, etc. They were made by “J Carlton by Dominique Gault.” It’s a French company that makes other miniatures but it has now discontinued the Tuscan line. So I used the same format, Nonno telling Stefano stories about some of the buildings, but also going into such medieval things as flag throwing, ghosts and devils, battles, the contrade of Siena, the calico storico of Florence, etc.

In both books, I hope I stressed the bond that can exist between a grandfather and a grandson. My mother’s father lived with us for years before he died. I have a photo of him and me in the back of the book.

L’Idea: What other literary project are you working on at the moment?

Paul Salsini: I’m deep into a story that’s unlike anything I’ve ever written. It’s contemporary and it deals with a contemporary subject. In fact, it’s so contemporary that I’m not sure how it’s going to end. That’s about all I’ll say.

L’Idea: If you had the opportunity to meet and talk to anyone in history, who would it be and why?

Paul Salsini: Probably Leonardo da Vinci. What an incredible, but also inscrutable, person! Was anyone ever so multi-talented?

L’Idea: In a critical moment for our nation and the world as it is the one we are living, what do you think writers like us could contribute to the society around them to alleviate the stress?

Paul Salsini: When I’m writing, I seem to enter into another world, a world that I may have created but which takes on a life of its own. I let the characters tell their stories in their own way. I’m hardly one to suggest what writers could do in these perilous times, but I think they are desperately needed now. They can take readers into universes where they can explore new ideas, discover new characters, visit new places, enjoy different stories. For myself, I find that I’m reading a lot more now, more fiction than I ever have, so I’m finding more new worlds.

L’Idea: Do you have a message for our readers?

Paul Salsini: Read, read, read.