By Elizabeth P. Vallone

Can tragedy be the source of good? Can the killing of hundreds, in the end, lead to a redemption of a horrific event?

Italians say: ‘Non c’è un male che non sia anche un bene,’ and ‘Non tutto il male vien per nuocere,’ meaning that “not all evil comes to harm.” The story about the bombing of Bari during WWII illustrates well that this saying is true.

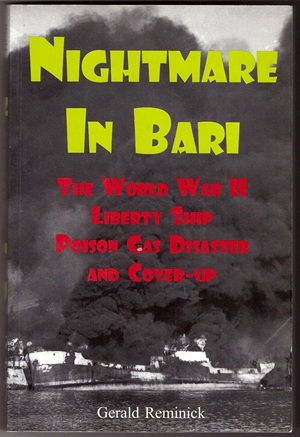

Few books have been written about the incident. Nightmare in Bari by Gerald Reminick is one such book. Reminich presents a compelling account that should be acknowledged as “Little Pearl Harbor”. This story should be told each year when we remember the sneak attack on Pearl Harbor in Hawaii that propelled the United States into WWII. The difference between the two events is that ‘Little Pearl Harbor’ led to the creation of one of the greatest cancer hospitals in the world – Memorial Sloan Kettering Hospital in New York City.

Few books have been written about the incident. Nightmare in Bari by Gerald Reminick is one such book. Reminich presents a compelling account that should be acknowledged as “Little Pearl Harbor”. This story should be told each year when we remember the sneak attack on Pearl Harbor in Hawaii that propelled the United States into WWII. The difference between the two events is that ‘Little Pearl Harbor’ led to the creation of one of the greatest cancer hospitals in the world – Memorial Sloan Kettering Hospital in New York City.

All the information in this article comes from Gerald Reminick’s book, and the statistics about Pearl Harbor come from New Orleans’ World War II Museum.

Chemical weapons were outlawed in 1925 at the Hague Convention. All nations agreed that the use of poison gas by major belligerents constituted a war crime.

So, let’s begin with the question, did Hitler use chemical weapons during WWII? Germany did manufacture Sarin gas, which could have killed hundreds of thousands of people, and Hitler’s generals wanted to use it. Hitler said no. Probably the only good thing Hitler did.

What about Little Pearl Harbor? Well, here is how the story goes…:

December 2, 1943, another date that Roosevelt should have called “a day that will live in infamy” was the date of ‘Little Pearl Harbor.’

Bari, Italy, located on the southeast coast of Italy, was home to a very large port that was responsible for moving ammunition, supplies, and provisions north to Rome for the allies. It was a very busy port and was illuminated 24 hours a day.

People in the surrounding towns were concerned that the port was a sitting duck for a surprise attack by Germany because of all those lights. For two days before the attack, German reconnaissance planes repeatedly flew over Bari. On the afternoon of December 2nd, Sir Arthur Coningham, British Commander of that area of Italy held a news conference. He was questioned about a possible attack. Being a pompous British aristocrat, he said, “I would consider it a personal insult if the enemy – Germany – would send even one plane near the Port of Bari.” Germany was losing.

Near the port was the Il Bambino Stadium. This stadium was a gift from Mussolini to Bari. The Italian dictator pledged to build a state-of-the-art stadium in any city that birthed the most baby boys. This was an incentive to achieve the goal of increasing the male population. The stadium in Bari was built and named ‘Il Bambino,’ “the little boy.”

This stadium was situated adjacent to the port of Bari. Two American baseball teams, recruited from the American ships in port, were hosting a game at exactly 7:30 in the evening. The port was filled with one destroyer from Canada, one from New Zealand, numerous cargo ships, coasters, liberty ships, cruisers, schooners, motorized row boats, and fort ships. Countries represented were the US, Canada, Britain, Norway, New Zealand, Holland, Greece, and Poland. Unbeknownst to the countries whose ships were in the port there was an American liberty ship, a kind of cargo ship that was carrying mustard gas as well as ammunition.

The US had no intention of using the gas, but since they knew Germany had a stockpile of sarin gas, Roosevelt thought perhaps they should have something on hand. But for the most part, no one knew what was on the ship called the John Henry. John Henry was a signer of the Declaration of Independence.

As bad luck would have it, the British guns, which were the first line of defense for the harbor, were not working. At 7:30 p.m., 50 German Junkers flying from the east dropped foil strips to jam the radar facilities. Immediately after the silver snowflakes fell to the ground, German bombers came in below radar and bombed the civilian areas; they hit the port.

Since the ships were lined up like dominos, most ships were hit. The American ship, the John Henry, which carried the mustard gas and ammunition, took a direct hit and it ripped apart the historic district of Bari. The stone houses folded like cardboard. The concussion from the ammunition on the John Henry and the other ships was felt for twenty miles around.

Every window in Bari and the surrounding areas was blown out. Flaming hunks of metal rained down like confetti. The fuel lines along the port were ruptured causing fires to spread along the water and the streets of Bari. The heat, mustard gas, and water combination vaporized the mustard gas, creating a cloud that drifted everywhere. The mustard gas liquid was on everything and in the air.

The injured allied military personnel were evacuated to the British Military Hospital and the New Zealand Military Hospital, deep into the city of Bari.

Around the time they built Il Bambino Stadium, Mussolini had a state-of-the-art multi-purpose hospital built. Military personnel injured by the bombing were sent there, besides the British and New Zealand hospitals. The young soldiers were not told what was wrong with them. Military hospital workers were ordered to turn the town’s residents away. The residents had to deal with their symptoms at home in their bombed-out buildings. The Bari area had 200,000 inhabitants; 60,000 were in Bari’s old town. Pearl Harbor had nowhere near the population of Bari. I’m sure you understand the implications.

There was chaos everywhere and the record-keeping of the civilians injured was practically nonexistent. Those soldiers and sailors in the water were burned by the chemical. They arrived at the hospital with their genitalia 10 times their normal size.

Symptoms of mustard gas poisoning were trouble breathing, the sensation of burning lungs, burns and blisters on the skin, sore throat, nausea, vomiting, blood disorders, and nervous system disorders.

Roosevelt and Churchill were immediately informed and they ordered a cloak of secrecy over the entire incident—a total news blackout that remained for years.

In 1948 Eisenhower’s memoir, The Crusade in Europe, he never mentions the Bari incident. Some journalists questioned him at the time. He said the incident was a consequence of an uncontrolled fire.

The deadly poison in the air and water would continue to kill days, months, and years after the attack. In that area of southern Italy, you only had farming and fishing. For decades fishermen would put up their nets and they would find a deteriorating mustard gas canister. They would go about removing it from their nets only to be burned and overcome by the gas, sickened.

The information about this deadly incident was not declassified for several decades. When the US started to study the effects of Agent Orange in the Vietnam War, they turned to the Bari incident. Exposure to Agent Orange often led to the growth of different kinds of tumors and leukemia.

A confidential landmark Bari report and a top-secret Yale University clinical trial demonstrated that nitrogen mustard (a more stable cousin of sulfur mustard) could shrink tumors. General Motors tycoons Alfred P. Sloane and Charles F. Kettering were asked to fund the Sloan Kettering Institute for Cancer Research (SKI), to create a state-of-the-art laboratory, staffed by wartime scientists, to synthesize new mustard derivatives and develop the first cancer medicine—known today as chemotherapy. Sloan and Kettering, both engineers, believed that American industrial research techniques could be applied to cancer research.

Thanks to the Bari incident, we’ve made incredible progress in the study of tumors. You can say chemotherapy was an offshoot of little Pearl Harbor.

The Bari incident had 23 ships sunk in the port, 10 damaged, and 1,000 allied soldiers killed, they believe. There is no way of knowing how many civilians died; the official sources claim 1,000, but Bari area had a population of 200,000.

The bombing of Pearl Harbor lasted two hours, while Little Pearl Harbor only minutes.

In Pearl Harbor, 100 civilians and 2,400 American soldiers died, 1,000 of them were wounded; 20 naval vessels were sunk, 8 of which were battleships, and 300 airplanes destroyed.

December 7th is coming, and I hope that day, besides commemorating Pearl Harbor, you also think of Little Pearl Harbor and the good that came out of that terrible incident, namely the birth of chemotherapy and the renowned Sloan Kettering Hospital in New York City.

Click on each image to see a documentary video on “Little Pearl Harbor”