Review by Tiziano Thomas Dossena

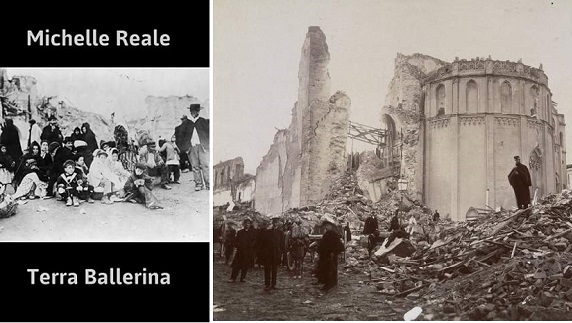

Michelle Reale states in her Preface, “Messina is never far from my mind or heart.” Why is it so? And why did she feel compelled to write poems about this city’s cataclysmic earthquake of 1908?

Reading the poems in Terra Ballerina, one can sense her involvement with this tragic event. We can postulate that it was developed not only because her maiden name is Messina, but because her early interest in finding out more about her namesake fostered an unexplained but instinctive attachment to the people who witnessed it. So, her spontaneous attachment to Messina grew into a feeling of love, compassion, and grief for its population. After all, isn’t the heart of a city the people who live in it?

The first poem, “The Night Before: Messina Opera House,” introduces us to a hypothetical couple attending a performance of Verdi’s Aida at the Messina Opera House, and their

“…slow procession

home down streets that they could not

possibly know, will soon be filled with

sad eyed orphans

and the dead.”

The impossibility for this couple to know what dreadful future awaits them and all the other citizens of Messina does not mean they were not made aware that something bizarre is in the air. The poet has introduced elegantly this instinctive awareness:

“…Outside, a faint lightning strike illuminates

like a mirage. The couple blinks. An ancient Roman belief

deems such a strike unclean,

Uncleanliness is a sin in and of itself.

The couple walk(s) home, but this time, hands apart,

deep into their own pockets. The tinged sky is a mystery…”

The omen of the lighting is then followed by another presage, “a luminous glow creates a magnetic field unseen / and destined to be unremembered by most…”, introduced in the following poem, aptly named “Presage.’. But even more, in the same poem, “Holy water dishes are bone dry in churches everywhere…” Did God’s houses of prayer lose His protection?

In the third poem, which gives the name to this poetry collection, the fury of the earthquake and the Tsunami that followed are described powerfully:

“The main shock stuns with disbelief.

Daybreak rouses from a stubborn winter.

Slumbering and transparent clouds, like fallen angels, float

on first hot, then cold wind.

Red glow like the fire of hell

arches heat and church

walls quake. Electricity discharges

fire from the tips of God’s fingers…

…A seawall rises and the earth

twirls and rises and dances…”

The verses are direct and leave no chance of misunderstanding.

The next poem, “By the Numbers,” is just a list of data related to this event, but somehow its simplicity brings to the reader the possibility of grasping the magnitude of the drama that has unfolded.

The next poem, “By the Numbers,” is just a list of data related to this event, but somehow its simplicity brings to the reader the possibility of grasping the magnitude of the drama that has unfolded.

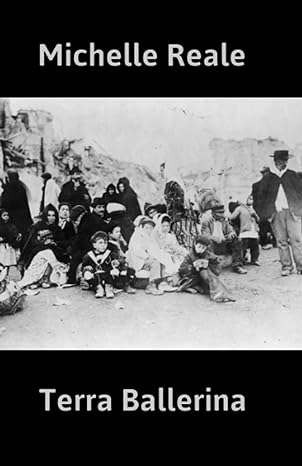

Furthermore, photographs of the era and newspaper clippings are intercalated among the poems, illustrating the dimension of the disaster.

“Thirty-One Seconds,” the fifth poem of this collection, illustrates the implausibility that such a short time is “…long enough to complete / a cycle of life and death…”

In the next poem, “The Light that Meets the Eye,” Reale makes us conscious that even the previously dead are “…reanimated in a convulsive heap…”

In “A Tremor Is Not an Afterthought,” the poet reminds us that “Before the eye can see, the body will feel…” and that “…Clocks will mark the / hour in perpetuity…”

“Benedizione” (The Blessing) is a compelling poem that describes the aftermath of the natural disaster, with the

“…dead, in their dusty nightclothes

broken fingers, and blood in

their hair. They are praying too

as they hover above the wreckage,

the wailing and the pounding hearts…”

In this unnatural scenery, a survived priest “…continues his desperate incantation…” These verses are awe-inspiring and are capable of giving the readers a few chills…

“Salvo,’ and the poem in prose “Ancora Respiro” address the concept of the survivors’ reactions to waiting to be rescued. “Lacrime” reminds us that the

“Survivors, dying of thirst, / cup their hands and scoop sea water / to rinse parched mouths…” and that “…They might as well be drinking / their own tears.”

“Addio’ faces the conundrum that survivors face in trying to remember their families, their neighbors, and their city, while those memories are themselves the reason for leaving.

“Necropolis” describes Messina as a city of the dead, a necropolis, “…a city unlucky, scorned, / doomed to forget what stubbornly / cannot be remembered,” while “Baraccopoli” portrays the shantytown that is being erected in the aftermath of the earthquake.

The last poem, “City Without Memory,” is the proper closing to the collection, being an intense contemplation of the necessity to forget.

This collection of poems by Michel Reale reaches our hearts, bringing us close to the people who suffered such a catastrophe as well as to the poet, who is capable, with her evocative language, of also building a bridge between the readers and her soul.

OTHER BOOKS BY MICHELLE REALE: