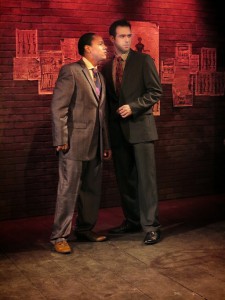

When a handsome man wants something badly, he grabs our attention. In “All Gone West” by John Attanas, set in New York City during the early 1950s, that guy is Sam Samos (actor Joseph Robinson), a chatty bartender who wants a jazz club and a girl to call his own. Back story: during 1945, when Sam was in the Army, he bonded with a black G.I. Sonny Green (Jesse Means), a talented saxophonist and composer, over their love of jazz. Though Sam is not a musician, he sees himself as an impresario. The Program states that this “tale of sacrifice for a passion is staged with cast of six and a live jazz quartet.”

However, the word “sacrifice” is inaccurate. Sam Samos neither scrimps nor saves to open his nitery. Why go through even a second of self-deprivation when there’s the racetrack, a quick gamble for greenbacks, along with access to mobsters and loan sharks? In this way, “All Gone West” comes close to finding the laziest and least admirable leading man to build an up-from-nothing drama around. Moreover, Sam Samos is surrounded by a squadron of losers, arrested development types who, like him, have placed their bets on instant gratification.

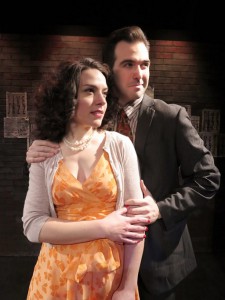

There’s Mary Elizabeth Brady (Kristen French), a Bronx brunette, a bored City College typist by day, frustrated mistress by night. Despite having employee benefits that include free tuition, it never occurs to Mary to take classes to improve her lot in life. Instead she hopes to earn that “Mrs.” degree. When Sam meets her in a bar, she’s nursing a Pepsi and fretting about her intoxicated date, Professor Joe Hanley (Glen Williamson), a hopeless drunkard who romances his cocktails till he falls down. This May-December dalliance has been dangling for three years (and two months), though Hanley never promises to end his marriage nor his drinking. With three strikes against him, the aged alcoholic isn’t much of an opponent; it’s an odds-on favorite that Sam will win this hand. But there’s emptiness at the core of this relationship, too. His attraction to Mary is patently shallow, based on her beauty and his desire to get her naked. Though Sam claims she “inspires” him, only his sexual appetite seems stimulated.

The nightbirds on Sam’s antenna include Willie (Anthony Bosco), a racetrack tout and Sam’s conduit to fast cash. Sonny Green, who’s been signed by Vanguard Records, shows promise though his prison past and drug habit cast long shadows. Rounding out the group, Kristen Booth portrays two tarts; as Peggy, she parties and shoots up with Sonny Green and, as a nameless hooker, she is hired to work the club crowd and increase the take for the money-lenders.

Anti-romantic characters with broken wings are intriguing. Either they’ll make our flesh crawl or redeem themselves and soar. And the friendship of a white and black man during the racially polarized 1950s is bound to fire up the pistons. Any moment the secrets, clashes, and revelations will amp up the action, right? Wrong. After guiding his vehicle out to the parkway, Attanas seems to have run out of fuel. The first engine stall is with his bland protagonist.

Though “All Gone West” shares a milieu and an era with “Guys and Dolls,” Sam Samos is never as sympathetic nor as fascinating as gambler Nathan Detroit, so wonderfully written as the perfect combination of contradictions: nervous and cool, downtrodden and upbeat, afraid of commitment and completely in love, his emotional gears turning in one direction, then in reverse. In contrast, Sam has no paradoxes to play off and, when his business fails, he sheds the pain too easily. When Mary offers to get a second job to help pay the loansharks, Sam refuses. But since the club is sinking, and Sam has a losing streak at the track, it’s unclear how he’s able to repay his debt to the gangsters. Why does Willie get beaten up, then shot, and not Sam, too?

Other scripts have featured characters who are not admirable in any way and yet have fashioned a gripping narrative nevertheless. But “All Gone West” has too many predictable beats and very little dramatic tension. As one example, while Miss Adelaide exerts much effort getting Nathan Detroit to take her to City Hall, Mary hesitates only a little before falling into bed with Sam, admitting that she really “likes sex” and he’s the best lover. To say that this would be highly uncharacteristic for a nice Catholic girl in the early 1950s is an understatement.

Another stall is Attanas’s tactic of having Sam or Mary narrate the story’s transitions with meek monotony. Telling versus showing is boring.

Do the damaged nightbirds straighten up and fly right? As we wait in vain for racial tensions to escalate, there’s only a brief moment where Mary hesitates to shake Sonny’s hand. And instead of the supporting players being taken on an emotional journey, the dramatist kills them off. The two principals start over in California. In other words, they are no more nor less than their worst day. They’re only much tanner.

Reducing the pleasure further are annoying mistakes with the set and costuming. Though only a few pieces of furniture (chairs and tables) are used, instead of leaving the table-chair set-up intact and hidden behind a curtain until needed, the stagehands drag these noisily across the set after every scene until the audience is ready to scream.

Costume Designer Nicholas O. Staigerwald is incompetent. Obviously, he has never seen a poster of Elizabeth Taylor in “Butterfield 8” or “Cat on a Hot Tin Roof,” or he would know that a 1950s woman wore a full slip under clothing and a bullet-proof bra. But Mary’s often-seen underwear is not the only wrong detail. A 1950s secretary would wear a starched shirtwaist or a pencil skirt with a twin sweater set, not the mish-mash the actress is tricked out in. During Mary’s theatre date, she would wear a cocktail hat and gloves. Her coat would be a sack shape with smocking in the rear to accommodate the fullness of 1950s skirts and crinolines. The footwear is so wrong that it becomes one more visual failure.

The sound design by Howard Fredrics was very well executed down to the dialing sounds of a rotary phone. Fredrics could have looped in the jazz vibes of the quartet who play just off stage, too, because having live musicians there, while pleasant, is not enough to shore up the shaky bones of “All Gone West.”

— — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — —

“All Gone West” closes on April 18, 2015 1hr. 50min. (1 intermission) Teatro Circulo 64 E 4th St, New York, NY 10003; For tickets call: (212) 505-1808 This play opened Mar 28, 2015