By Elizabeth Palombella Vallone

My growing up years were filled with recollections of the ‘old country,’ since my parents didn’t come to the United States until 1947.

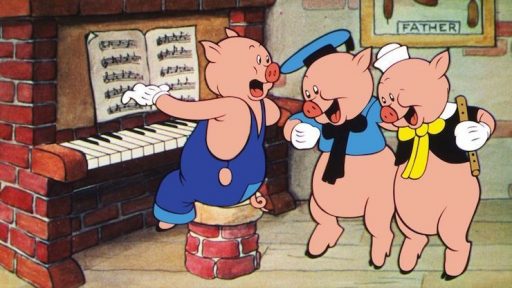

My father, in particular, loved to tell stories. One of his favorites was when Disney’s Silly Symphony of the “Three Little Pigs” came to the town theater in late 1933. Word spread that the cartoon trilogy of the little pigs and little foxes trying to catch the little pigs was not to be missed.

The depression was still on. Parents could not afford to buy movie tickets when the average family had 6 children. The boys had to literally scrounge around to get the money for the ticket.

My father decided to go to the junkyard. He brought a hammer and hacksaw with him. The idea was to find a piece of copper and turn it in at the salvage yard. After a couple of hours of searching, he found a small piece of copper attached to a motor. The hacksaw and hammer succeed in getting him a piece of copper. It wasn’t a very big piece, but it would translate into enough money to buy a ticket.

So, my father made his way to the theater. The crowd was large and unruly. How people got the money to buy the tickets was beyond him, though the junkyard was full of scavengers. He pushed into the crowd and everyone kept shoving forward ramming into the entrance doors. The force was so fierce, it managed to break the entrance doors off its hinges and splinter the wood. The police had to be called for crowd control.

It was dad’s lucky day, as his grandfather was Chief of Police. He got in easily and got a great seat.

When the show was over, everyone whistled the tune “Who’s afraid of the big bad wolf, the big bad wolf” as they made their way home. The tune was so catchy, the whistling continued well past the day the show left town.

My mother too had her stories. The first I will share had to do with the public ovens. Her grandmother had prepared a large pan with stuffed calamari. It was brought to the oven to be baked. They all waited on the balcony, watching for the delivery boy to come with their dinner, which hung on the biker’s handlebars.

When they saw him, they got to their feet and called to him. “Here, here! We’re the ones who get the calamari!” The inexperience biker rider became distracted, hit a bump. He and calamari went over the handlebars. The pan flipped, the calamari slithered across the dirty sidewalk and stopped below the balcony. The curses that rang out were loud and the little ones started to cry. Everyone knew there would be no dinner that night. Bread, sliced tomatoes and olive oil would have to do.

The story that made the most impression on me was one told to me when I was an adult. It was January 1991 and the bombing of Bagdad had begun. There were 1000 sorties and 88,500 tons of bombs dropped. This was vividly shown on CNN and other networks for a month. As we watched the Bagdad sky light up and heard the commentators talk about the hundreds of sorties flown over Bagdad night after night, my mother went into a PTSD episode. She curled up in a ball and was crying, shaking and screaming.

After my sister and I calmed her down, she told the story of the war and the bombing of Bari.

Firstly, she said that in September 1943 the British 1st Airborne Division took control of Bari and the surrounding towns. The British roamed the area of lodging for their officers and for female companionship. Gang rapes were not uncommon. Of all the soldiers making their way north, the women feared the British the most.

At about 7:25 on December 2, 1944, the air raid sirens rang out and everyone knew what to do. The women and the children marched into the countryside heading for the farmhouse a cousin had designated as their safe house. There were no men. Young men were conscripted into the military and the old men were forced to serve in the civil defense corps in town.

My mother, who was 16 at the time, made her way inland with her mother, sister, little brother, grandmother, aunt and neighbors of the farmhouse while the bombardment raged.

The lights from the explosions could be seen for miles. It was like no other they had ever seen before – a kaleidoscope of red, blues, yellows, white. The sounds were deafening.

That evening, 105 German Junkers Ju88A-4 twin-engine bombers came from the west and surprised attacked Bari. Ships and trucks arrived all day and night, unloading and/or loading ammunition supplies and provisions. Allied forces counted on this storage facility as they made their way north to Rome.

The brightly illuminated port facilitated the attack, making the port of Bari a sitting duck. By the end of the bombing, many American, Polish, Norwegian, English and Dutch warships were sunk and other merchant ships damaged.

Window glass was shattered for 7 miles from the site. A fuel pipeline was severed and the ships that were not hit by bombs were covered in flaming fuel oil. This created a similar situation to Pearl Harbor – men abandoning ship found themselves in oil-drenched waters.

| Ships damaged in the raid over Bari (From Wikipedia.org) | |||||

| Name | Flag | Type | GRT or Displacement |

Status[8] | Notes |

| Ardito | 3,732 GRT[8] | Sunk | |||

| Argo | Coaster | 526 GRT[8] | Damaged | ||

| Aube | Cargo ship | 1,055 GRT[8] | Sunk | ||

| Barletta | Auxiliary cruiser | 1,975 GRT[8][9][10] | Sunk | Forty-four crew killed. Four men from the militarized crew killed in action and four men were wounded. The military crew had twenty-two men killed in action, fourteen missing in action and forty wounded. Raised in 1948–1949 and repaired.[9] | |

| HMS Bicester | Hunt-class destroyer | 1,050 GRT[8] | Damaged | ||

| Bollsta | Cargo ship | 1,832 GRT[8][11] | Sunk | Raised in 1948, repaired and returned to service as Stefano M.[8] | |

| Brittany Coast | Cargo ship | 1,389 GRT[8] | Damaged | ||

| Cassala | Cargo ship | 1,797 GRT[8] | Total loss | ||

| Corfu | Cargo ship | 1,409 GRT[8] | Total loss | ||

| Crista | Cargo ship | 1,389 GRT[8] | Damaged | ||

| Dagö | Cargo ship | 1,996 GRT[8] | Damaged | ||

| Devon Coast | Coaster | 646 GRT[8][12] | Sunk | ||

| Fort Athabasca | Fort ship | 7,132 GRT[13] | Sunk | ||

| Fort Lajoie | Fort ship | 7,134 GRT[8][14] | Sunk | ||

| Frosinone | Cargo ship | 5,202 GRT[8][15] | Sunk | ||

| Genespesca II | Cargo ship | 1,628 GRT[8] | Sunk | ||

| Goggiam | Cargo ship | 1,934 GRT[8] | Total loss | ||

| Grace Abbott | Liberty ship | 7,191 GRT[8] | Damaged | ||

| Inaffondabile | Schooner | Unknown[16] | Sunk | ||

| John Bascom | Liberty ship | 7,176 GRT[8] | Sunk | Four crewmen, ten armed guards killed.[17] Wreck scrapped in 1948.[18] | |

| John Harvey | Liberty ship | 7,177 GRT[8] | Sunk | Cargo of mustard gas bombs. Thirty-six crewmen, ten soldiers, twenty armed guards killed.[17] Wreck scrapped in 1948.[18] | |

| John L. Motley | Liberty ship | 7,176 GRT[8] | Sunk | Cargo of ammunition. Thirty-six crewmen, Twenty-four armed guards killed.[17] | |

| John M. Schofield | Liberty ship | 7,181 GRT[8] | Damaged | ||

| Joseph Wheeler | Liberty ship | 7,176 GRT[8] | Sunk | Twenty-six crewmen, fifteen armed guards killed.[17] Wreck scrapped in 1948.[19] | |

| Lars Kruse | Cargo ship | 1,807 GRT[8] | Sunk | Nineteen crew killed.[20] | |

| Lom | Cargo ship | 1,268 GRT[8] | Sunk | Four crew killed.[21] | |

| Luciano Orlando | Cargo ship | Unknown[8] | Sunk | ||

| Lwów | Cargo ship | 1,409 GRT[8][22] | Sunk | ||

| Lyman Abbott | Liberty ship | 7,176 GRT[8] | Damaged | ||

| MB 10 | Armed motor boat | 13 tons displacement[8] | Sunk | ||

| Norlom | Cargo ship | 6,326 GRT[8] | Sunk | Six crew killed. Refloated November 1946, scrapped 1947. | |

| Odysseus | Cargo ship | 1,057 GRT[8] | Damaged | ||

| Porto Pisano | Coaster | 226 GRT[8] | Sunk | ||

| Puck | Cargo ship. | 1,065 GRT[8][23] | Sunk | ||

| Samuel J. Tilden | Liberty ship | 7,176 GRT[8] | Sunk | Ten crewmen, fourteen U.S. soldiers, three British soldiers killed.[17] Wreck scrapped in 1948.[24] | |

| Testbank | Cargo ship | 5,083 GRT[8] | Sunk | Seventy crew killed.[25] | |

| Vest | Cargo ship | 5,074 GRT[8] | Damaged | ||

| HMS Vienna | Depot ship | 4,227 GRT[8] | Damaged | ||

| Volodda | Cargo ship | 4,673 GRT[8] | Sunk | ||

| HMS Zetland | Hunt-class destroyer | 1,050 GRT[8] | Damaged | ||

Unbeknownst to all, bombs of mustard gas were secretively stored on an American ship named the John Henry which took a direct hit.

The town of 250,000 people was subjected to the bombs, the first bombs hitting civilian areas, then followed by a cloud of mustard gas that caused damage to the lungs and blindness. Military and civilians made their way to the British General Hospital or the New Zealand Hospital located in deep within Bari. There were 628 military casualties; the number of civilian casualties was never ascertained. The military was immediately ordered to drop a curtain of secrecy regarding the mustard gas bombs.

No details were to be acknowledged to anyone.

Fortunately for my mother and the others in the farmhouse, the wind blew the mustard gas cloud away from where they hidden. When the noise of the bombing finally subsided, my mother and her family heard the sound of tanks, trucks, jeeps and army boots on the road not too far from where they were concealed. The sound went on all night and everyone’s nerves were frazzled.

About four-thirty in the morning, the road noises quieted down but they heard the sound of footballs. Round and round the farmhouse someone walked. They couldn’t tell if it was one person or more than one person.

The women became hysterical. Some shouted they were going to be killed, others that were going to be raped, others prayed to God.

Suddenly there was a knock on the window shutters. The hysteria reached fever pitch, with people pounding the floor, walls, screaming and crying. Suddenly a cousin who had not succumbed to the hysteria shouted: “Calm down! Calm down! It can’t be soldiers; they would not knock! They would just burst in.” Courageously, she opened one of the window shutters and there was a very old man – a cousin who was on the civil defense duty. He told them they could make their way back.

My mother had never told that story to anyone, not even my father, who she was married to 40 years by then.

I learned firsthand how devastating trauma can be and how it can lay dormant for years. Though my sisters and I were sorry that my mother suffered so deeply by the bombing of Bari, it spurred us on to ask for more stories.

As an aside, it was not until 1967 that the U.S. government declassified the documentation detailing the account of the bombing of Bari. It was kept quiet from 1944 until then.