If we agree that wisdom springs from the integration of vast experience, reflection, and intellectual humility, we might come to appreciate the unexpected font of insight from an oft-maligned personage: That of Giacomo Girolamo Casanova (1725-1798)!

Casanova was a man whose myriad of experiences included euphoric highs and abysmal lows that might have been deemed insurmountable by most. Yet this “prince of adventure” always bounced right back in his quest to drink as much pleasure from the cup of life as possible, right up to the very last drop. Despite his strong Christian faith, he nevertheless abhorred– if not feared– the thought of having the curtain go down on a “still interested observer” of the theater of life, not having concrete proof of a certain afterlife.

Casanova was a man whose myriad of experiences included euphoric highs and abysmal lows that might have been deemed insurmountable by most. Yet this “prince of adventure” always bounced right back in his quest to drink as much pleasure from the cup of life as possible, right up to the very last drop. Despite his strong Christian faith, he nevertheless abhorred– if not feared– the thought of having the curtain go down on a “still interested observer” of the theater of life, not having concrete proof of a certain afterlife.

“There is an immaterial God who answers prayers.”

Casanova has gone down in history as an unabashed womanizer, a doer of shady deals, a gambler, swindler, at times even a prisoner. Yet this same protagonist was also a university graduate, businessman, at times a soldier, a diplomat, and respected author and poet. He was sometimes welcomed by society, and at other times banished from respectable circles and sooner or later from most major cities in Europe as well. This passionate Venetian lover was able to charm people (not only women) from every social stratum—from commoner to pope, with his gioia di vivere, non-ending resilience, and ability to easily morph from one public persona into another. Ultimately, his was a lifelong quest to gain acceptance and respect while struggling to maintain a balance between what Freud might call his instinctual drives versus his fragile capacity for self-control.

Casanova has gone down in history as an unabashed womanizer, a doer of shady deals, a gambler, swindler, at times even a prisoner. Yet this same protagonist was also a university graduate, businessman, at times a soldier, a diplomat, and respected author and poet. He was sometimes welcomed by society, and at other times banished from respectable circles and sooner or later from most major cities in Europe as well. This passionate Venetian lover was able to charm people (not only women) from every social stratum—from commoner to pope, with his gioia di vivere, non-ending resilience, and ability to easily morph from one public persona into another. Ultimately, his was a lifelong quest to gain acceptance and respect while struggling to maintain a balance between what Freud might call his instinctual drives versus his fragile capacity for self-control.

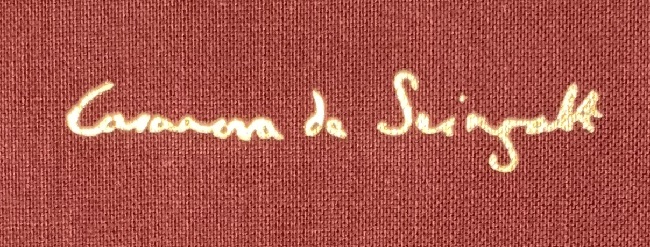

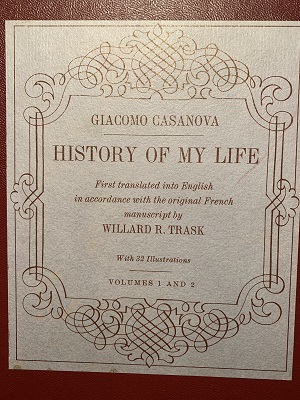

In his memoir History of My Life, written towards the end of his life, Casanova reflected candidly about his “errors”, which resulted from being “irresistibly drawn by anything which could excite [his] curiosity”. It is this very candor that makes us unable to pass judgment on the way he chose to live, but instead leaves us rather grateful for sharing what he learned. While, unlike the typical religious or philosophical texts to which most people turn to be inspired, Casanova’s self-analysis serves as a thought-provoking source of inspiration, or at the very least provides an interesting look into the personal beliefs of a man the world was quick to stereotype.

In his memoir History of My Life, written towards the end of his life, Casanova reflected candidly about his “errors”, which resulted from being “irresistibly drawn by anything which could excite [his] curiosity”. It is this very candor that makes us unable to pass judgment on the way he chose to live, but instead leaves us rather grateful for sharing what he learned. While, unlike the typical religious or philosophical texts to which most people turn to be inspired, Casanova’s self-analysis serves as a thought-provoking source of inspiration, or at the very least provides an interesting look into the personal beliefs of a man the world was quick to stereotype.

- We are free agents because God gave us the power of reason, which is a “particle of the Creator’s divinity”. “Destiny”, on the other hand, he believed is a figment of the imagination and to believe in fate limits our power to be actors in our own life.

- Just because we are free, does not mean we should do whatever we please. Casanova believed that we should use our reasoning power to make ourselves humble and just.

- The wise person is not a slave to his/her passions, but rather has the self-control to defer acting until calm. Casanova attributes his past errors to being a victim of his senses and acting more from feeling than reflection.

- There is an immaterial God who answers prayers.

- Prayer kills despair. Casanova believed one should pray often, then trust that God will answer your prayers if you act accordingly.

- Pray for grace, then believe you have received it, even if appearances seem to be the opposite. Casanova’s inexhaustible optimism was what both men and women found irresistibly charming about him.

- Good comes from evil and evil comes from good. Casanova believed that it is our job to straddle the ditch that divides the two sides of human nature. To do so takes not just strength, but courage. He believed that confidence without courage is useless.

- One becomes a fool when in a fool’s company. This serves as a reminder to choose the company we keep wisely. The people we surround ourselves with have a great influence on who we become.

- Character shows up in the face. Casanova believed in a pseudoscience dating back to Aristotle, called physiognomy. This is the belief that a person’s personality, character or temperament is revealed in his facial features or expressions. For example, a person with a high forehead would be considered intelligent, etc. To the extent that it might be relevant today one who frowns frequently might be seen as an unhappy person and vice versa. A good reason to smile often!

- Hatred kills the unfortunate man who fosters it. Casanova admittedly found it easier to “forget” rather than forgive those who betrayed or mistreated him, but the bottom line was the same. He knew that anger if festered did more harm to the person holding on to it than to the transgressor.

- The Importance of Good Food. Casanova admitted to eating once a day to keep himself healthy, and that he also had a penchant for highly seasoned dishes, like “maccheroni prepared by a good Neapolitan cook”.

- Happy are they who know how to obtain pleasure without harming anyone. Quite endearing is the author’s social consciousness. While admitting he was never a saint, he also deeply cared about the wellbeing of those he loved. This was evident in the way the women with whom he had affairs expressed a true affection for him.

- “God demands only that we practice the virtues he has given us and has given us nothing which is not meant to make us happy” Casanova believed that some of the of our God-given virtues included self-esteem, desire for praise from others (also found in Maslow’s hierarchy of needs), vigor (or practices that foster good health), courage and moral freedom.

- Life is the only treasure we possess, and those who do not love it do not deserve it.

- The importance of self-love: “I have always admitted”, wrote Casanova, “ that I was the chief cause of all the misfortunes which have befallen me. I have rejoiced in my ability to be my own pupil and in my duty to love my teacher.”

To be human is to live a life of peaks and valleys, as we strive toward continual self-betterment. Casanova, in allowing us to become observers in the open theater of his life, reminds us we are not alone in our struggle—as St Augustine knew all too well– to avoid temptation and stay (as best we can) on the path of virtue.

Reference: Giacomo Casanova, History of My Life (English translation 1966 from the French by Willard R. Trask). New York: Harcourt, Brace & World, Inc.