Article by LindaAnn Lo Schiavo

In 2012, as workmen dug beneath a parking lot in Leicester, England, they made an amazing discovery. A skeleton was found among the remains of what had been the city’s Greyfriars friary. DNA tests confirmed these bones belonged to King Richard III [1452 – 1485] of the House of York. The former British monarch was killed at the Battle of Bosworth Field in 1485 but his final resting place had remained a mystery for 527 years.

In Great Britain and Western Europe, history is often hiding beneath the pavement. Not long ago, a Pugliese family, determined to fix a broken toilet pipe, accidentally uncovered 2,500 years of artifacts, escape tunnels, Roman granaries, and other marvels that were sleeping under an unremarkable house they had purchased in 1981.

“The very first layers of Lecce date to the time of Homer, or at least according to legend,” said a local historian and author Mario De Marco in a N.Y. Times interview, noting that invaders were enticed by the city’s strategic location and the prospects for looting. “Each one of these civilizations came and left a trace.”

As British journalist Michael Day explained to the London readership of the Independent [U.K.] in 2015, Luciano Faggiano was about to find out that archaeological relics turn up regularly. “He went from Lecce café owner to Indiana Jones in the space of a few weeks.”

Upon retrospect, there had been elusive clues. For almost 20 years, their tenants had been complaining of dampness. Eventually, however, these residential leases expired and Mr. Faggiano, a trained chef, wanted to convert his property to a trattoria with living quarters on the 2nd floor for himself, his wife Anna Marie Sano, and their youngest son, Davide. That was the plan in the year 2000.

Because it was so frustrating when filthy sewage kept backing up at 56 Via Ascanio Grandi, he summoned his two older sons Marco and Andrea to help dig a trench. Recalling the ordeal for an audience at the Italian American Museum on Mulberry Street on October 11, 2017, Andrea Faggiano said, “He told us it would take about a week. Instead it took years!”

“We were not trying to be secretive,” he emphasized. “We always worked with all the windows and doors open. We had filed for a permit. Obviously, we were not trying to hide.” Each day they removed buckets of dirt, loaded them into the car, and dumped the mess at a farm his father owned, a meadow where Marco, his oldest brother, raises bees. Hard labor seemed to be never ending — — until one day the authorities showed up.

Then another unexpected occurrence! Investigators shut down the “excavations.” Suddenly, it was no longer a father’s quest to fix a broken toilet. The Faggianos were informed that, in the eyes of the law, they were operating an unapproved archaeological dig.

The inspectors explained that if residents’ shovels went below a certain number of meters, a different permit was required. Why? Because unlike tunneling in (say) New York City, an exploration of Lecce’s underground is bound to unearth relics. “Wherever you dig a hole,” said a city official, “centuries of history will be found.” The site was padlocked for an entire year, as the authorities brought in a professional archaeologist to assess the cultural heritage at stake here.

City officials determined that this treasure trove required supervision and management. Luciano Faggiano was given a choice: wait for Lecce’s government to come up with funding or bear the cost himself and abide by their rules. Moreover, he was told he could not STOP digging — — until he hit bottom. The family decided to bring in their own architect and self-finance the project. “My father had become obsessed,” laughed Andrea.

It took years — — yes, years! — — until they found the bottom.

At one point, Faggiano had to tie a rope around Davide, who was then a 12-year-old and the only member of the family small enough to be lowered down into the dark recesses. “We were using buckets,” explained Andrea. “And it was not uncommon for the bucket filled with dirt and relics to turn right over onto Davide as he was being hauled up.”

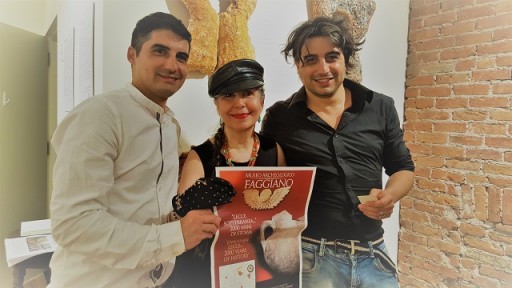

Before Marco and Andrea Faggiano traveled to New York City to make their first American presentation about “Museo Archeologico Faggiano, 2000 Anni di Storia,” they made a short film in their unique museum. It was an incredible look at a subterranean world, whose layers revealed themselves slowly.

The deepest level revealed relics from the Messapians, an Iapygian tribe which inhabited southern Apulia in classical antiquity, approximately the 5th Century B.C.

Another level showed signs and well-preserved insignias from The Knights Templar, a Catholic military order founded in 1119 and active from about 1129 to 1312. The order, which was among the wealthiest and most powerful, became a favored charity throughout Christendom and grew rapidly in membership and power. Quite prominent in Christian finance, Templar knights, in their distinctive white mantles with a red cross, were among the most skilled fighting units of the Crusades. The Faggiano brothers had a copy made of the Templar carvings they found — — a five-petaled flower inside a circle — — and presented the plaque to Cav. Joseph Scelsa, founder of the Italian American Museum.

For a time, the structure was used as a convent where nuns prepared the dead for burial. Andrea showed the photo of an archbishop’s ring surrounded by over 100 diamonds. Since the family uncovered secret tunnels and coffins that held babies, he said it was clear the nuns had access to male company.

In addition to ancient tombs, the Faggianos found a granary, a well, cisterns, and underground escape routes. Roman coins, religious proverbs carved on stone arches when it was a nunnery, medieval remnants, bones, and heaps of Byzantine pottery gradually came to light, over 3,000 items in all. Most of it is being studied by government archeologists. The family was permitted to show a small portion in their museum.

Several audience members had, in fact, already visited Museo Archeologico Faggiano. And the short film shows how a visitor can move through each chamber, looking down into the past via clear glass panels built into the flooring. If they revise the film, they would do well to include much larger still photos and pause the film so these fascinating objects can be enjoyed.

For a unique history tour, visit this museum the next time you are in Lecce.

Online: http://www.museofaggiano.it/