Interview by Tiziano Thomas Dossena

Stanislao G. Pugliese, Ph.D. is a Professor of History and the Queensboro UNICO Distinguished Professor of Italian & Italian American Studies at Hofstra University, and a Fellow of the Hofstra Cultural Center.

Stanislao G. Pugliese, Ph.D. is a Professor of History and the Queensboro UNICO Distinguished Professor of Italian & Italian American Studies at Hofstra University, and a Fellow of the Hofstra Cultural Center.

L’Idea Magazine: Prof. Pugliese, you are a Distinguished Professor of History at Hofstra University and you have been teaching at that University since 1993, for almost thirty years. It’s quite an achievement. After so many years, the connection between the job and job site may become almost symbiotic. Is that so for you and Hofstra?

Stanislao Pugliese: My relationship with Hofstra University is indeed central not just to my career but my adult self. I was an undergraduate student at Hofstra, majoring in History and Philosophy from 1983 to 1987, and extremely fortunate in having outstanding professors who nurtured a first-generation college student, a child of immigrants. John T. Marcus taught European intellectual history; Tom Belmonte taught the cultural anthropology of Italy, and Pellegrino D’Acierno introduced me to Vico and Gramsci. Their classes changed my life by allowing me to see myself as both a potential teacher and scholar. I was extremely fortunate to be hired for a full-time, tenure-track position in 1994 after a year as an adjunct instructor. The History Department offered me the job – even before I had finished my Ph.D. – not because I was a former student they insisted, but because they sensed my passion about teaching. In the three decades since then, I have been most fortunate in the support of the department and the university administration, and the enthusiasm of our students, who never fail to amaze me. One highlight among many has been teaching in Venice for the Study Abroad program. In addition to teaching, I’ve been very fortunate to direct academic conferences and edit proceedings on a wide range of subjects, from the history of Italian Jews, Primo Levi, Frank Sinatra, and soccer. Hofstra has never said “No” to any new course or conference I’ve proposed. I’m not sure I would have that freedom at another institution. So yes, my relationship with Hofstra is not the usual relationship one has with their workplace.

L’Idea Magazine: You taught many courses through the years, ranging from “Fascist Italy” to “Sex, Crime, and Violence in Venice,” “Confronting Italian American Stereotypes” and “History of the Mafia.” Are there subjects for new courses that you would like to teach at this point of your life or have you touched basically almost all the subjects you wanted to?[explain why]

Stanislao Pugliese: I’m always looking for new courses to offer students, new ways of learning and thinking about History. Recently I started teaching a course on fascism and anti-fascism because it’s critical for students to understand that fascism isn’t something that ended in 1945. As a scholar of fascism, I feel an ethical and moral imperative to teach about the consequences of the historical period and the current manifestations of fascism around the world 0151— and in the United States. This spring semester I offered a new course, “Screening Italian American History,” in which we examine topics through documentaries such as Gianfranco Norelli and Suma Kurien’s “Pane Amaro,” iconic films such as “The Godfather” and lesser-known films such as John Turturro’s “Mac” and Nancy Savoca’s “Household Saints.” In the fall, I’m teaching another new course, “Black Italy: Race, Culture, and Colonialism in Two Worlds.”

Stanislao Pugliese: I’m always looking for new courses to offer students, new ways of learning and thinking about History. Recently I started teaching a course on fascism and anti-fascism because it’s critical for students to understand that fascism isn’t something that ended in 1945. As a scholar of fascism, I feel an ethical and moral imperative to teach about the consequences of the historical period and the current manifestations of fascism around the world 0151— and in the United States. This spring semester I offered a new course, “Screening Italian American History,” in which we examine topics through documentaries such as Gianfranco Norelli and Suma Kurien’s “Pane Amaro,” iconic films such as “The Godfather” and lesser-known films such as John Turturro’s “Mac” and Nancy Savoca’s “Household Saints.” In the fall, I’m teaching another new course, “Black Italy: Race, Culture, and Colonialism in Two Worlds.”

This course will examine the long history of cross-cultural interaction between the Italian peninsula, the Mediterranean basin, and Africa. Topics will include ancient Rome and the Punic Wars, Southern Italy as the first “globalized” culture, the religious tradition of “the Black Madonna,” the racialization of Southern Italy as “Africa” and migration to the Americas, the “conquests” of Libya (1911) and Ethiopia (1935-36), the political ramifications of contemporary migration to Italy, the history and intersection of Italian Americans and Black Americans, and the debate over Italian Americans and “whiteness.” I’d like to teach a future course on the changing conceptions of gender and gender roles in Italian and Italian American cultures. And eventually — after much new reading — a course on the history of the Mediterranean as the first globalized, cosmopolitan society.

L’Idea Magazine: In reference to the educational response of the students, do you find it more challenging teaching subjects involving Italian history or Italian American topics?

Stanislao Pugliese: Italian and Italian American history present both problems and opportunities. Students come to Italian and Italian American history with many stereotypes. We try to read and unpack these stereotypes: how and why were they created? What are their pernicious consequences? How can we counter and challenge these stereotypes? Then I ask my students to think about what is particular to Italian and Italian American history and what traits are almost universal. Because I was trained in Italian history, in teaching Italian American history and culture, I depend very much on the work of my colleagues in the Italian American Studies Association. And I very strongly believe the fields should have stronger ties.

L’Idea Magazine: The average American seems to be very ignorant, or at least has a very superficial, stereotypical knowledge of Italians and Italian Americans. What do you believe could be done to obviate such misconception of our ethnic group’s values?

Stanislao Pugliese: This is a Sisyphean task. It seems that no matter how much prominenti and academics criticize the stereotypes, they persist. I’m beginning to wonder if the problem is actually more deeply rooted: that the stereotype of the mafioso or the buffoon satisfies some psychological desire of the general public and is therefore almost ineradicable. Another problem is to be able to distinguish truly great art, such as Coppola’s The Godfather and Scorsese’s Mean Streets from kitschy trash such as Spielberg’s Shark Tale. But even such cultural products as Jersey Shore can give us some insight into Italian American culture. It may not be the image we wish to project, but it’s there and should be studied like any other cultural phenomenon. Academics and scholars do a tremendous job in producing studies about Italian and Italian Americans and increasing our understanding; perhaps we have to do a better job in reaching out to the non-academic audience. I do many public speaking events at local libraries, schools, and adult community groups and find there is a great hunger for more sophisticated and nuanced portrayals of our culture.

L’Idea Magazine: Do you believe that offering more courses on Italian history would at least give the opportunity to some of our young people to discover their real roots and what Italianità is all about?

Stanislao Pugliese: As I imagine is the case at other schools, at Hofstra there are Italian American students who are deeply interested in their history and culture, and then there are those who show no interest at all, or at least don’t take classes. How many Italian American students have I advised who are taking Spanish rather than Italian? Why? Why this lack of interest in the madrelingua? Maybe they think Spanish is more useful as the demographics in the country change? Without speaking with them, I can’t tell if it’s because they are divorced and estranged from their culture and are simply not interested, or they may be interested but can’t fit the courses into their schedules and busy lives. It is always fascinating to see Italian American students learn new things about Italian history; they are often amazed by things they don’t know, like the history of Italian Jews. Then there are those students who are not Italian American but are fascinated by the culture and genuinely want to know more about Italy or Italian American culture. It’s exciting when they recognize parallels with their own ethnic histories and make connections. The Italian diaspora resonates with students across a wide range of ethnicities: Jews, African Americans, students from the Caribbean, Latinx.

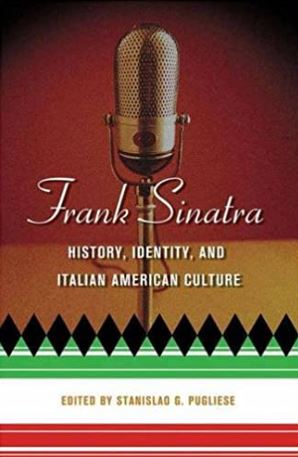

L’Idea Magazine: You wrote two books on ‘The Voice’, “Frank Sinatra: History, Identity, and Italian American Culture” and “A Century of Sinatra: Gay Talese and Pete Hamill in Conversation.” He was not really a historical character, so what arouse your interest in him?

L’Idea Magazine: You wrote two books on ‘The Voice’, “Frank Sinatra: History, Identity, and Italian American Culture” and “A Century of Sinatra: Gay Talese and Pete Hamill in Conversation.” He was not really a historical character, so what arouse your interest in him?

Stanislao Pugliese: Oh but he was very much a historical character. Sinatra came along at the moment of the “invention” of the teenager and the “bobbysoxer.” The microphone revolutionized singing and his original persona was unique. I underestimated Sinatra at first. I’ve come to see him as a pivotal and complex character in Italian American history. And he was part of a generation (Fiorello LaGuardia a little older and Joe DiMaggio among many others) who changed the perception of Italian Americans in the minds of Americans in the middle third of the twentieth century. Together with WWII, in which Italian Americans were the largest ethnic group fighting in the military, and which changed the minds of many American soldiers (that Italian Americans could be good Americans), Frank Sinatra and other Italian American singers such as Tony Bennett, embodied the American dream. And as Pete Hamill said, Sinatra, immigrants and the children of immigrants reminded America what it really meant to be American when it seemed America had forgotten. What I find fascinating about Sinatra is that he wanted to be both a padrone and a paesano, without realizing, tragically, that you can’t be both.

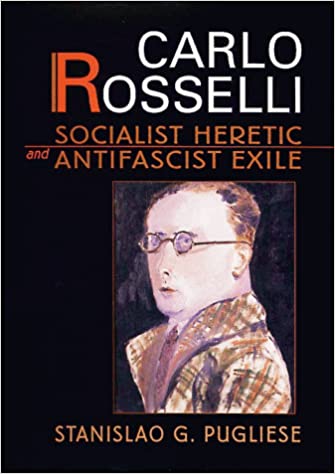

L’Idea Magazine: Your monograph “Carlo Rosselli: Socialist Heretic and Antifascist Exile” was translated into Italian, Romanian and Russian. Could you tell our readers what prompted you to research this man and write about him?

L’Idea Magazine: Your monograph “Carlo Rosselli: Socialist Heretic and Antifascist Exile” was translated into Italian, Romanian and Russian. Could you tell our readers what prompted you to research this man and write about him?

Stanislao Pugliese: When I was in graduate school and thinking about a possible dissertation topic, some people suggested I write about Italian fascism. But the thought of spending so much time reading, thinking, and writing about those people really didn’t appeal to me. I was much more fascinated with the anti-fascist Resistance. Much had already been written about Gramsci and the PCI so I instead became interested in the largest non-Marxist movement, Giustizia e Libertà. This led me to the founder, Carlo Rosselli, a fascinating character. Born into a wealthy, assimilated Jewish family with deep ties to the Risorgimento (they were friends of Mazzini), Carlo and his younger brother Nello represented the “active” and “passive” wings of anti-fascism. Carlo gave up a position as a professor of political economy and threw himself into the underground, financing the first anti-fascist publication, non Mollare! Nello concentrated on writing the history of the nineteenth century, which gave him an opportunity to be anti-fascist “between the lines.” Carlo was also involved with Lauro de Bosis’s flight over Milan where he dropped anti-fascist leaflets over the city, and with Filippo Turati’s flight into France to escape fascist persecution. Carlo was subsequently arrested, tried, and sentenced to confino on the island of Lipari. In 1929, he escaped and made his way to Paris where he founded Giustizia e Libertà and published his major work, Socialismo liberale. He was among the first to go to Spain to defend the Spanish Republic, and lightly wounded in action. Recovering at a spa in Bagnoles de L’Orne in Normandy, he was assassinated on June 9, 1937, along with Nello, by French cagoulard, paid by Ciano and Mussolini. If I had an opportunity to re-write that first book, it might be a dual biography, with alternating chapters devoted to Carlo and Nello. Considering the world we live in right now, I think the so-called “passive” resistance embodied by Nello, was (and is) not passive at all; it is just another kind of anti-fascism, maybe just as important as the “active” Resistance. After their assassinations, Giustizia e Libertà faltered a bit but was reborn as the Partito d’Azione during the Resistenza armata against fascist Italy and the Nazi occupation. GeL and the PdA attracted many of the most prominent intellectuals of twentieth-century Italy, from Carlo Levi and Primo Levi to Ernesto Rossi, Ferrucio Parri, and Sandro Pertini. The dissolution of the Partito d’Azione and the Parri government in late 1945, so profoundly depicted by Carlo Levi’s book L’orologio, represents a tragic turn in Italian history.

L’Idea Magazine: You appear to be also fascinated with Ignazio Silone, Primo Levi, and Carlo Levi. You also translated some of their works… Did Fascism, the Partisan Resistance, and the Italian Civil War have such a ponderous effect on your interests?

L’Idea Magazine: You appear to be also fascinated with Ignazio Silone, Primo Levi, and Carlo Levi. You also translated some of their works… Did Fascism, the Partisan Resistance, and the Italian Civil War have such a ponderous effect on your interests?

Stanislao Pugliese: If there is an overarching theme to my interests, research, and writing, it has been the attempt to bring the history and ideas of these largely unknown men and women to an American audience. There was a time (the 1930s and 1940s) when Ignazio Silone was widely read in the United States. Today, that’s sadly not the case. Carlo Levi, best known for his memoir of a year in confino in Basilicata, Cristo è fermato a Eboli, also wrote Paura della libertà, a title (Fear of Freedom) that is just as prescient today as it was first published in 1939.  Primo Levi has become known as the Italian Holocaust writer, but ironically he didn’t want to be known as a Holocaust writer, or a Jewish writer, or an Italian writer, but just a writer. I’ve translated Silone Notes from a Swiss Prison and Carlo Levi’s essay “Paura della pittura” because I strongly believe the works of these men deserve a wider audience. I was also honored to edit the English translation, published by Verso, of Claudio Pavone’s Una Guerra civile: saggio storico sulla moralità nella Resistenza, considered by many scholars to be the most important work in the subject.

Primo Levi has become known as the Italian Holocaust writer, but ironically he didn’t want to be known as a Holocaust writer, or a Jewish writer, or an Italian writer, but just a writer. I’ve translated Silone Notes from a Swiss Prison and Carlo Levi’s essay “Paura della pittura” because I strongly believe the works of these men deserve a wider audience. I was also honored to edit the English translation, published by Verso, of Claudio Pavone’s Una Guerra civile: saggio storico sulla moralità nella Resistenza, considered by many scholars to be the most important work in the subject.

L’Idea Magazine: Among your translations the memoir by Andrea Bocelli sets itself apart, being not the original work of a literary scholar but one of a singer. Was it quite a different experience from your usual work to translate his book? Did you have to meet at all with Bocelli for the translation?

Stanislao Pugliese: This was a strange project and unfortunately I never got to meet Bocelli. My wife was working for a publishing company considering whether or not to purchase the English language rights to his memoir. She brought the book home and asked me to take a look at it. Her publisher asked me if I would consider doing a quick translation, just so they could get an idea of the book. So I did a very quick translation, with the understanding that this was only for internal review. But the publisher took the manuscript of my translation and sold it (without my permission or knowledge) to another publisher who printed it as it was, without any review or corrections.

Stanislao Pugliese: This was a strange project and unfortunately I never got to meet Bocelli. My wife was working for a publishing company considering whether or not to purchase the English language rights to his memoir. She brought the book home and asked me to take a look at it. Her publisher asked me if I would consider doing a quick translation, just so they could get an idea of the book. So I did a very quick translation, with the understanding that this was only for internal review. But the publisher took the manuscript of my translation and sold it (without my permission or knowledge) to another publisher who printed it as it was, without any review or corrections.

L’Idea Magazine: “Dancing on a Volcano in Naples: Scenes from the Siren City” is your new book, soon to be published. Could you reveal to our readers what is the book about? This is not your first book on Naples, is it?

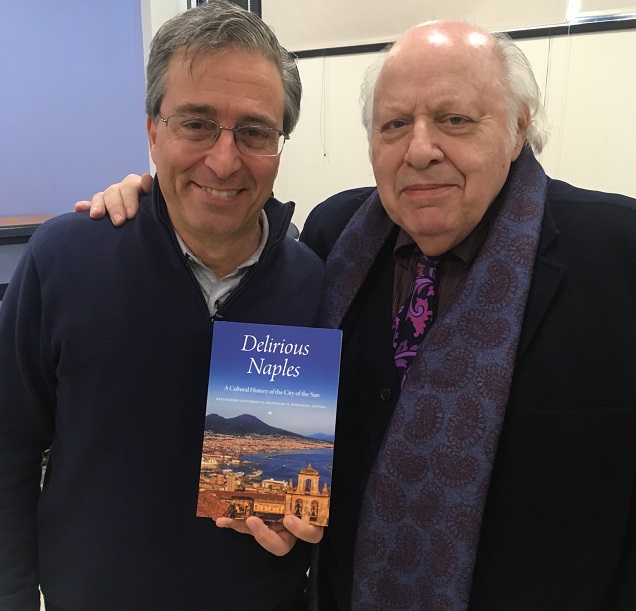

Stanislao Pugliese: My colleague Pellegrino D’Acierno and I organized a three-day conference at Hofstra, NYU, and Columbia University on Naples. We had dozens of scholars from Italy and the United States taking part, including Maestra Stefania Rinaldi, direttrice of the Coro di Voci Bianche of the San Carlo Opera house, conducting Hofstra students in a concert of Neapolitan music at the Casa Italiana of NYU. It was extraordinary! The proceedings were published in Delirious Naples: A Cultural History of the City of the Sun. I have long been fascinated by the city and after the Silone bio, my publisher, Jonathan Galassi, asked if I wanted to write on Naples. So I eagerly accepted the offer.

Stanislao Pugliese: My colleague Pellegrino D’Acierno and I organized a three-day conference at Hofstra, NYU, and Columbia University on Naples. We had dozens of scholars from Italy and the United States taking part, including Maestra Stefania Rinaldi, direttrice of the Coro di Voci Bianche of the San Carlo Opera house, conducting Hofstra students in a concert of Neapolitan music at the Casa Italiana of NYU. It was extraordinary! The proceedings were published in Delirious Naples: A Cultural History of the City of the Sun. I have long been fascinated by the city and after the Silone bio, my publisher, Jonathan Galassi, asked if I wanted to write on Naples. So I eagerly accepted the offer.

L’Idea Magazine: Which one of your many books was the hardest to write and why?

Stanislao Pugliese: The Naples book is by far the most difficult book so far. Because so much has been written about the city, and so many excellent works, it has been almost paralyzing in trying to approach the subject anew. So instead of a comprehensive history — which would take a lifetime — I decided to write about specific aspects of Naples: there are chapters on coffee, soccer, WWII and the “Four Days of Naples,” Pulcinella, graffiti, book publishing, and death. I have been traveling to Naples and interviewing people for a decade and hope to finally finish in a year or two.

L’Idea Magazine: In 2020 you published the essay “The Eternal Tendency Toward Fascism.” Could you briefly talk about that essay’s content and the reference to today’s world?

L’Idea Magazine: In 2020 you published the essay “The Eternal Tendency Toward Fascism.” Could you briefly talk about that essay’s content and the reference to today’s world?

Stanislao Pugliese: There are historians and political scientists who argue that “fascism” was a political ideology of a particular time (1922-1945) and place (Italy and Germany). But “the eternal tendency toward fascism,” a line from Carlo Levi’s book Fear of Freedom, written in 1939 as war clouds gathered over Europe, reminds us that fascism did not end in 1945; that there lurks in human beings a dark and hidden (and sometimes not-so-hidden) desire to relinquish our freedom and deny the freedom of others. This is similar to what Primo Levi would write in 1974, a time known as gli anni del piombo in Italy:

“Every age has its own fascism, and we see the warning signs wherever the concentration of power denies citizens the possibility and the means of expressing and acting on their own free will. There are many ways of reaching this point, and not just through the terror of police intimidation, but by denying and distorting information, by undermining systems of justice, by paralyzing the education system, and by spreading in a myriad subtle ways nostalgia for a world where order reigned, and where the security of a privileged few depends on the forced labor and the forced silence of the many.”

This is a chilling quote, for it aptly expresses what is taking place – today – in the United States.

Another frighteningly accurate diagnosis is Umberto Eco’s famous essay “Ur-Fascism” in which he outlines 14 common points of fascism; again, with every one of the 14 present in today’s political culture.

L’Idea Magazine: Some websites list you as one of the authors of the book “Galeazzo Ciano, Diary, 1937-1943.” What was your involvement with that book and why are you sometimes excluded from the list of authors. Is there maybe more than one edition?

L’Idea Magazine: Some websites list you as one of the authors of the book “Galeazzo Ciano, Diary, 1937-1943.” What was your involvement with that book and why are you sometimes excluded from the list of authors. Is there maybe more than one edition?

Stanislao Pugliese: Robert Miller, an independent scholar and publisher, asked me to edit a new edition of Ciano’s diary. I did so and he published the book in 2002. I don’t know why sometimes my name appears as editor and in other editions it doesn’t. For better or worse, I have spent much of my professional career editing volumes; either new editions like Carlo Levi’s or seven volumes of conference proceedings. I also serve as editor of Palgrave Macmillan’s series on Italian and Italian American Studies, which have published over 80 volumes. It has become known as an important resource for scholars around the world.

L’Idea Magazine: You also wrote many essays, papers, articles, and books about Italian Jews. What do you believe distinguished them from other European Jews?

L’Idea Magazine: You also wrote many essays, papers, articles, and books about Italian Jews. What do you believe distinguished them from other European Jews?

Stanislao Pugliese: My dissertation on Carlo Rosselli introduced me to the history of Italian Jews. Fascist spies in Paris branded Giustizia e Libertà “the movement of Jewish intellectuals.” Thirty years ago, when I told people I was studying Italian Jews, some reacted by saying “Italian Jews? There’s no such thing.” Their idea of being Italian was so tied to being Roman Catholic, that they could not conceive of Italian Jews. That began to change with the renown of Primo Levi in the 1980s. Italian Jews have a fascinating history going back two millennia. And because Italy is still today marked by regionalism, it is more correct to speak of various Italian Jewish communities, rather than a singular identity. So the community of Rome is different from that of Florence, or Turin. But a common denominator is the consciousness of an identity always struggling between assimilation and tradition. Italy has had a long and varied history with regard to the Jews. There have been eras and places of relative safety and accommodation, in contrast with periods (surely more common) of persecution. Venice, after all, was the site of the first ghetto (1516) to be followed by one in Rome (1555). Yet Italy also had two Jewish prime ministers, the mayor of Rome in 1904 was Ernesto Nathan, an Italian Jew, and the most highly decorated office in WWI was Emanuele Pugliese, another Italian Jew (but no relation to me).

L’Idea Magazine: You were a Visiting Scholar at Oxford University, Harvard University, the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, and the Istituto Campano per la Storia della Resistenza, in Naples, Italy, just to name a few. Could you somewhat compare these experiences?

Stanislao Pugliese: I have been extraordinarily fortunate to be the recipient of the generosity of wonderful institutions. My time at the University of Oxford gave me a glimpse of a world so utterly different from that of my parents that I wandered around campus reflecting on how the son of immigrants from the Mezzogiorno could be working in the Bodleian Library. One beautiful summer day, I was strolling past the chapel of Madeleine College while the chorus was making a recording. The doors were thrown open to the warm breeze and there was a chair perfectly placed at the entranceway. So I sat down and eavesdropped on the beautiful medieval songs. It was a sublime moment and fond memory. At Harvard, instead, I marveled that I was in the Widener Library, the refuge of anti-fascist historian Gaetano Salvemini. At the Holocaust Memorial Museum, I participated in a seminar on Jewish Resistance to the Holocaust. In contrast to Oxford and Harvard, which were joyful experiences, the Holocaust Museum could not be anything but somber and sobering. Entering every day, I was reminded of the enormous moral and ethical responsibility of the historian in preserving the past. The Istituto Campano per la Storia della Resistenza hosted me as I did research on the “Four Days of Naples,” that seminal moment at the end of September 1943 when — no longer waiting for the arrival of the British and American armies — the people of the city rose up against the Nazi occupiers. Since my father was from a small village in the province of Avellino, not far away, the people of Naples always have a special welcome for me.

L’Idea Magazine: They say that history repeats itself. As a historian, do you believe that the invasion of Ukraine is a repeat of past abuses on that country, or is this a new situation as a whole?

Stanislao Pugliese: They also say “History doesn’t repeat itself, but it does rhyme,” meaning that while the same events won’t play out exactly the same, there’s no way to make sense of the present without understanding the past. There are many parallels here with the past, but many ironies as well. Putin claims to be “saving” Ukraine from Nazis, when the president of the country, Valodymyr Zelensky is Jewish and lost relatives in the Holocaust. The Russians and Soviets, including Ukrainians, died by the millions (some historians say as many as 25 million) to defeat fascism. Today, the only fascist in this scenario is Putin himself. But I think the Russian leader, in his fanaticism and megalomania, may have finally and fatally miscalculated. This only makes him far more dangerous.

L’Idea Magazine: As a Historian and an Italian American, what is your reaction to the Christopher Columbus statues situation and the cancel culture issue as a whole?

Stanislao Pugliese: As a historian, I recognize both the historic impact of Columbus on history –perhaps no one other than Jesus Christ himself has had such an impact – and the role Columbus plays in the historical imagination of Italian Americans. The problem is that Italian Americans have so elevated Columbus – literally putting him on a pedestal – they have conflated man, statues, and holiday with Italian Americanness itself. This I believe is a mistake. Even by the standards of his day, Columbus was thought to be a vicious colonial governor, recalled by the Spanish Crown. Italian Americans should not feel threatened by criticisms of Columbus, but because we have so much invested in him, we can’t accept any criticism. Italian Americans should have some historical empathy with Indigenous peoples. We too were colonized people in the Mezzogiorno. If we really need a historical personage to embody the Italian American immigrant experience, perhaps Mother Francis Cabrini would be a better choice. Or Sacco & Vanzetti, but as anarchists, I doubt most Italian Americans would embrace them. But why do we need any one person to define who we are? There should be an Italian American Heritage holiday, complete with parades and Italian street bands (I play in one), poetry readings, film screenings, scientific demonstrations, and the whole panoply of Italian American contributions to the United States. The focus on Columbus, who really doesn’t represent the Italian American experience, detracts from a better understanding of the critical role Italian Americans played in American history.

L’Idea Magazine: If you had the opportunity to meet anyone from the past or the present and talk to them, who would that person be, and what would you ask?

Stanislao Pugliese: I’m afraid that meeting someone I admire from the past would be a disappointment so perhaps best to let them remain in the past.

L’Idea Magazine: Are you working on any new projects at this time?

Stanislao Pugliese: I’m always working on the new Naples book; if not writing, then reading; if not reading, then watching Napoli play in Serie A; if not watching soccer, thinking about Naples.

L’Idea Magazine: What do you like to do on your free time?

Stanislao Pugliese: As I mentioned above, I play in an Italian street band, founded in 1923 (yes, we are 99 years old) and, as of last year, serve as the band director. I started playing when I was 13, so this year makes 44 years; quasi mezzo secolo! I used to play soccer in an over-40 league, but had to stop because I was so out-of-shape. On weekends, I enjoy seeing my extended family and working in the garden.

L’Idea Magazine: A message for our readers?

Stanislao Pugliese: Obviously and by definition, the readers of L’Idea are custodians of Italian culture. That implies a certain responsibility and so I would gently remind them of the three maxims of the Italian American Writers Association:

1) Write or be written;

2) Buy our books;

3) Read our books.

It’s important for scholars, academics, and ordinary people to write the history of Italian Americans, or else our history will be written by others. This is not always terrible. There are people who are not Italian Americans who are outstanding scholars of Italian America. I think immediately of my friend and colleague Professor William J. Connell, who holds the LaMotta Endowed Chair in Italian Studies at Seton Hall University. Together, we edited The Routledge History of Italian Americans. Bill wrote the introduction and an excellent essay on the age of Columbus. He was the prime mover behind this project; the result is a monumental work of history with three dozen collaborators from the USA and Italy, covering more than 500 years. At a very modest $55, it should be in every Italian American home. And the Italian translation should be in every Italian home!

It’s important for scholars, academics, and ordinary people to write the history of Italian Americans, or else our history will be written by others. This is not always terrible. There are people who are not Italian Americans who are outstanding scholars of Italian America. I think immediately of my friend and colleague Professor William J. Connell, who holds the LaMotta Endowed Chair in Italian Studies at Seton Hall University. Together, we edited The Routledge History of Italian Americans. Bill wrote the introduction and an excellent essay on the age of Columbus. He was the prime mover behind this project; the result is a monumental work of history with three dozen collaborators from the USA and Italy, covering more than 500 years. At a very modest $55, it should be in every Italian American home. And the Italian translation should be in every Italian home!