As the years pass, 68 to be exact, the memories of WWII fade further and further away. Unfortunately, parts of history are not always remembered and often not acknowledged. I wonder how many young people today realize that captured Italians, Germans, Japanese were removed from their theaters of war and brought to camps in the United States. The subject of these POWs doesn’t come up, I suspect. The number of WWII veterans is steadily dropping.

Occasionally, a novel will be published which will shine a light on an all but forgotten aspect of the war. Two books come to mind, The Hotel on the Corner of Bitter and Sweet and The Anguish of Surrender – Japanese POWs of WWII. One tells of the internment of Japanese Americans, their round-up, the conditions they endured and the implications after the war. The other is about the Japanese aversion to surrender. No American novel that I am aware of tells the story of the Italian POWs in the United States.

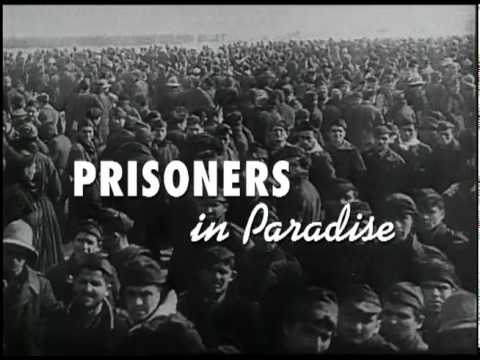

A number of years ago, a documentary entitled Prisoners in Paradise told their story, but a novel (historical-fiction or non-fiction) has not surfaced. In Italy, prisoners of the U.S. have published works about their experience in US POW camps, but I am not aware of any of those books being translated and marketed here. It’s a pity because their story should be remembered.

A number of years ago, a documentary entitled Prisoners in Paradise told their story, but a novel (historical-fiction or non-fiction) has not surfaced. In Italy, prisoners of the U.S. have published works about their experience in US POW camps, but I am not aware of any of those books being translated and marketed here. It’s a pity because their story should be remembered.

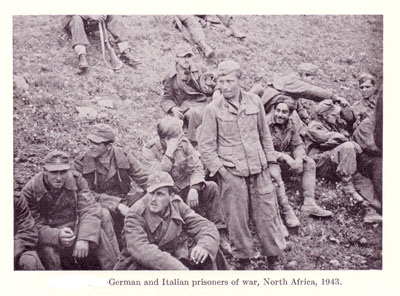

Between 1940 and 1945, 425,000 POWs landed on American soil. The majority of these men (350,000) were from Germany. There were camps for the German, Italian and Japanese in all but three states – Nevada, Vermont and North Dakota. They were on the East Coast in places such as Governor’s Island (NYC), the Raritan Arsenal (NJ), Fort Monmouth (NJ) Port Johnson (NJ), Brooklyn (NY), Camp Shanks (Rockland County, NY), (Bayonne (NJ). On the West Coast they were housed in an old fort on Angel Island in San Francisco Bay, the Los Angeles area, the Midwest (Michigan, Wisconsin, Nebraska, and Illinois), the Northwest, (Wyoming, Utah, Colorado) and the South (Louisiana, Texas, Alabama.) Usually these camps were put into areas where facilities to house them already existed, and where there was some type of labor shortage because of the war (factories, farms, munitions depots, ports, etc).

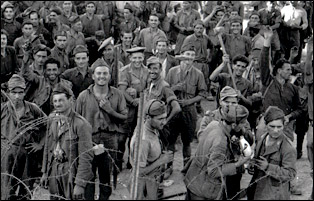

The Italian POWS numbered 51,000 and were placed in the 21 camps in 18 states. Generally speaking, the Italian soldiers were sympathetic to the Allies. Knowing this, the government gave them the option of renouncing Italy and joining the Italian Service Units. If they did this, they would be treated well, be given a job on their facility and could have freedom of movement with permission. The general enlisted man readily agreed for fear of being put in divisions being sent to fight Japan. The officers who were more educated and indoctrinated in Fascism were more reluctant. They had a real crisis of conscience and felt more loyal to their cause. If the men continued to swear allegiance to Italy they were considered non-compliant, referred to a NONS, and many were shipped to Hereford, Texas. Four thousand Italian officers were put on the Hereford Reservation.

The Italian POWS numbered 51,000 and were placed in the 21 camps in 18 states. Generally speaking, the Italian soldiers were sympathetic to the Allies. Knowing this, the government gave them the option of renouncing Italy and joining the Italian Service Units. If they did this, they would be treated well, be given a job on their facility and could have freedom of movement with permission. The general enlisted man readily agreed for fear of being put in divisions being sent to fight Japan. The officers who were more educated and indoctrinated in Fascism were more reluctant. They had a real crisis of conscience and felt more loyal to their cause. If the men continued to swear allegiance to Italy they were considered non-compliant, referred to a NONS, and many were shipped to Hereford, Texas. Four thousand Italian officers were put on the Hereford Reservation.

One would think that the Italian prisoners would be welcomed with open arms in the NY/NJ and Boston area, but they were looked upon with suspicion when they first arrived. The Italian-Americans were finally convincing people they were Americans first, and now all these enemy combatants arrived to spoil things. However, that did not last long and in a short time the Catholic parishes near the installations were inviting the men to Sunday dinners, dances and outings. Those housed in the NYC area were treated to trips to museums, the Bronx Zoo, the Empire State Building and the usual tourist attractions of New York City. All social and cultural events were denied to the NONS in all the other states where they were placed.

One would think that the Italian prisoners would be welcomed with open arms in the NY/NJ and Boston area, but they were looked upon with suspicion when they first arrived. The Italian-Americans were finally convincing people they were Americans first, and now all these enemy combatants arrived to spoil things. However, that did not last long and in a short time the Catholic parishes near the installations were inviting the men to Sunday dinners, dances and outings. Those housed in the NYC area were treated to trips to museums, the Bronx Zoo, the Empire State Building and the usual tourist attractions of New York City. All social and cultural events were denied to the NONS in all the other states where they were placed.

To Californians, Japan was the real enemy. In the land of farmers and wine-makers, California, the Italian soldiers were enthusiastically received. Men were put to work in the fields or on fishing boats, earning $8.00 a month. The Catholic parishes ministered to their religious needs as well as social needs.

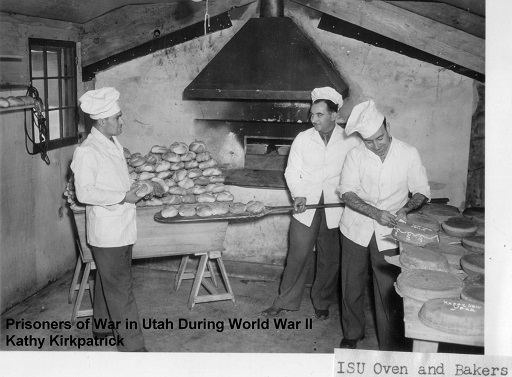

Italian prisoners of war contributed one millions hours of labor to the war effort. They were farm workers, bakers, ditch diggers, dock works, freight handlers for trucks, railcars, fulfilling the needs of the communities in which their camp was located.

To the Italian prisoners, the camps were almost paradise. Although there were instances of mistreatment, especially toward the NONS, they were kept in clean barracks, had hot showers, an abundance of food and they could spend the money they saved from their work at the local PX. The educated officers would often buy books, writing papers and utensils, supplies for painting, sculpting, woodworking, for activities which they would do in their spare time. With these skills they also earned extra money. They made jewelry from scrap metal, made furniture and cabinets for people who sought their expertise, painted portraits and even religious frescos for churches. Often, they did not take money for their work.

Five Italian prisoners died in Hereford, Texas, not too long before the war ended. It is not known if they died from disease, accident, or mistreatment. We do know that the NONS in Hereford built a chapel to inter their fellow officers there. The chapel was built using scavenged bricks, broken glass, and surplus material. Using their own money they purchased an altar, double French doors, and stained glass window. Since they knew they would be shipped home within a few weeks, they worked long and hard and completed the lovely chapel in three weeks.

The chapel eventually fell into disrepair, but it was restored not too long ago. It stands proudly in the middle of a corn field, a testament to the Italian officers who lived and died on the 800 acre where they were stationed for the duration of the war. Let us not forget the brave Italian men who fought for Italy during WWII and were brought to the United States as prisoners!