by Laura Klinkon

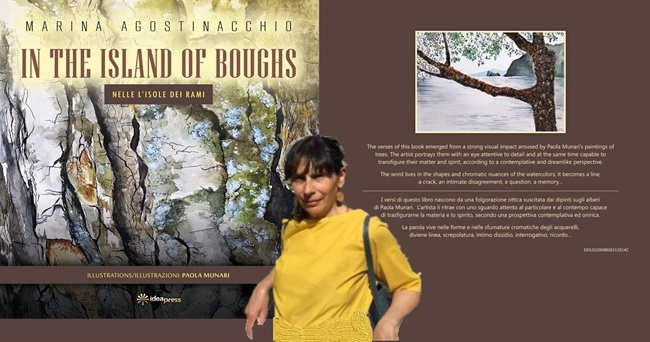

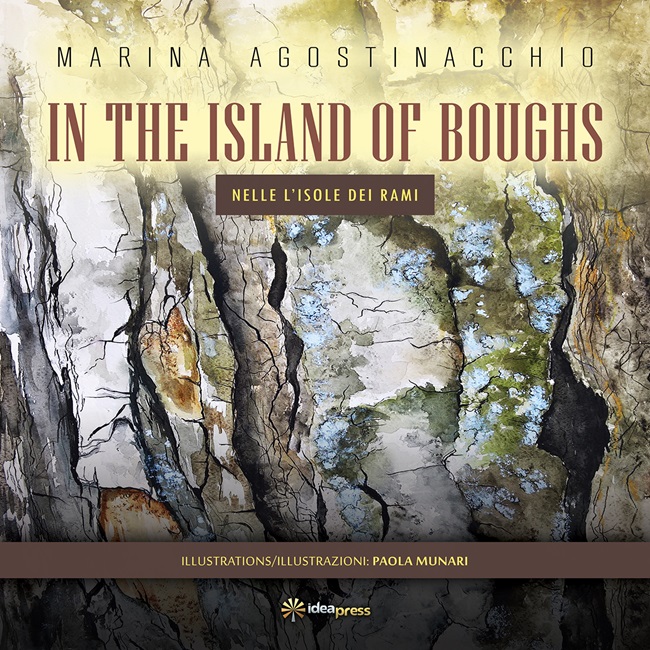

In the Islands of the Boughs, a collection featuring a translation of Nelle isole dei rami, is much more than a book of poetry. The original Italian poems written by Marina Agostinacchio, were inspired by watercolors of subjects in nature painted by the artist, Paola Munari. Each poem is an interpretation of a particular Munari painting that can be visualized on the page preceding each poem, giving the reader a dynamic experience of the different ways the subject may be interpreted. Typically, when a work of visual art is interpreted in writing, we expect the result to be an explanation of the work or a highlighting of its main elements; if the form is poetic, it is referred to as ekphrastic poetry.

You might think a word of Greek origin would not be necessary for such a simple concept, but in fact, several categories of ekphrasis have been identified by theorists. This review, on the other hand, will look at the approaches to ekphrasis in Agostinacchio’s book as variations on just two categories: literal or imaginative.

The other kind of interpretation involved in this collection is the translation of poetry, here accomplished by Tiziano Dossena; it can also be seen as literal or imaginative—the latter, in translation parlance, being referred to as “free.” There is also a prior interpretation that the artist Munari has made of the natural subject painted. As viewers will see, she highlights some visual aspects over others, which, in turn, has an influence over the poems.

The introduction to the collection explains that “The artist portrays [the trees] with an eye attentive to details and at the same time …transfiguring …matter and spirit, according to a contemplative and dreamlike perspective.” This is a definite clue that the imaginative perspective is at work in the painter’s work, though not precisely how it influences the poetry. However, we will not go into depth about Munari’s interpretations. Yet, even from a limited perspective, the multiple interpretations inherent in this volume make it an exciting book of poetry amenable to further, enthusiastic deciphering.

The main topic of both paintings and poems is trees, as the first poem “Loneliness of the Trunk” reminds us. In it, Agostinacchio calls attention to the “exasperated beauty” of the trunk that is “humanized in the cracks/where the tongue and the eye dwell/….” Immediately we know that this poem draws on the imagination not only in a sort of fairytale way but also in a whimsical way, referring as it does in the ending verses, to the silver elements in the painting, which the poet says she “believes in,” as a “footprint” leading to its “discourse.”

As poetry, In the Islands of the Boughs, is imaginative, whimsical, fanciful, and when read with attentive reference to the paintings, the VERSES can become powerfully evocative

It is interesting to note that the poet has titled her poems differently from the titles of the paintings she writes about. The poem titled “Stellar Movements” responds to the painting entitled “Leaves of a Deep Sea” — a clue that both painter and poet are engaging imaginatively in their unique ways. Agostinacchio actually seems to address those very differences in the first line of this poem when she refers to the vertical images in the foreground as “outposts” rather than “leaves,” the stronger image supporting their identification as trees. Yet, several lines later, the speaker/poet asks herself “Why have they brought me/here… [among]…/…tender azures….” No doubt, this is a fanciful poem, as corroborated by the mention of an image hidden among the “outposts:” “the gaze of an owl, vague,/a stranger in the hinted texture…,” and by a final identification of the lines in the upper part of the painting as “stellar movements.”

In the poem entitled “Clarity,” which responds to the painting “Vain Reflexes,” the artist’s and poet’s interpretations seem more in accord in that the poet/speaker is overtly self-referent. The painting shows a line of trees in autumn growing along the distinctly rounded edge of a pond, and the poet surmises that the ‘swaying silence’ has led her to envision her “clarities.” The poem requires some interpretation by the reader, due to the ambiguity of the word “clarities.” The pond reflects the trembling trees separated by the pond’s edge, where the speaker/poet seems to awaken to her own essence, choosing to be herself and “refractory” or unwilling to cross the pond’s edge.

As will be evident by now, the reader of In the Islands of the Boughs is being asked to engage in the interpretation, which is most effectively accomplished through reading both the poem and the painting as well. Imagine then, the translator’s responsibility! In light of the imaginative inventiveness of both painter and poet, the translator Dossena has made the wise choice of translating literally, for when a translator decides to apply his or her imagination, an already imaginative or fanciful poem could, as it were, go completely ‘off the rails.’

In the poem “Protection,” written in response to the evocative painting “Game of Weaves,” Dossena remains disciplined. The tree in this case is very contorted, parts of it suggesting a human body and growing what could be interpreted as hairs. Yet Dossena’s translation suggests this only when the poet herself verbally identifies hairlike and human elements with phrases such as “this falling of tufts,” and “proud folded hair,” and “I triple/the elbow and the knee….”

In “The Island” that answers to the painting, “Looking for Peace,” because of its delicacy, a reader would not expect to find images of “begging,” “tribal spirit,” and “rubble,” yet the words are translated literally, ending in the phrase “serenity of fingertips and water”…which ends the poem mystifyingly, as we expect the poet intended.

The painting, “The Silence,” might be considered a very simple painting of a log and branches washed up against a shore. But the poem, “Remains,” though asserting matter-of-factly in the first line that “The sea collects everything” goes on to imbue a sort of personified hero in that tree. Here is the poem in its entirety in the original Italian and as translated by Dossena:

The sea collects everything,

stones and tree carcasses.

It may be the intent of an Archangel

to disguise me with the sharpest

visor on the face. So

I defend myself from the mud, just

where the wave hits and the stones

respond.

— A sprout again.

Tutto raccoglie il mare,

pietre e carcasse d’albero.

Sarà l’intento di un Arcangelo

travestirmi con la visiera più

aguzza sul volto. Così

mi difendo dal fango, proprio

dove batte l’onda e i sassi

rispondono.

— Ancora germoglio.

As poetry, In the Islands of the Boughs, is imaginative, whimsical, fanciful, and when read with attentive reference to the paintings, the verses can become powerfully evocative…to such an extent that they may inspire the reader to devise his or her own imaginative interpretations. All adding to a uniquely enjoyable reading experience.