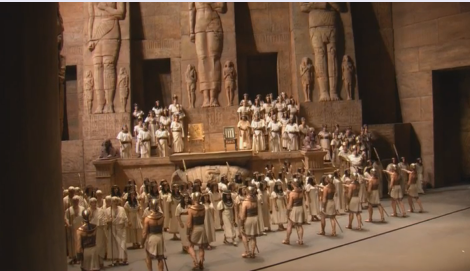

Imagine being immersed in an ancient world, with colossal stone columns, palaces and images of deities, a marvelous music surrounding you and, thank God, no cellular phones ringing: what else can one wish for? Well, how about some great arias and choruses? Done. Yes, that is exactly what experiencing “Aida” at the Metropolitan Opera is.

Based on a 1988 production by Sonja Frisell, with a set designed by the inventive Gianni Quaranta reflecting the original libretto’s descriptions to a T, but with his own flair, this opera offers a plethora of costumes that would impress anyone (Dada Saligeri proved that it could be done again and again). The famous return from the battle of Radames, with abundance of troops marching in various colorful and authentic looking costumes, and with horses, a carriage and a group of slaves, perfectly matched the grandiosity of Verdi’s “Triumphant March,” which made even more of an impact on the spectators than usual because of this visual effect. There was even a comic relief (do not expect a repeat, though) with one of the wonderful looking white horses that pulled the carriage showing an unexpected jumpiness, thumping its right hoof gracefully to show his unwillingness to be on stage and at times attempting to bite the hand of the phlegmatic attendant, arousing the laughter of the public.

Apart from these wonderful setting, this opera has so much value of its own and the singers offered such a valiant performance that I would rate this production a 4 and a half stars. The missing half star is due to the fact that somehow the First Act showed a slight tedium maybe due to an inadequate study of the performers’ movements on stage or maybe to the unfortunate temperature control in the theater, which was duly adjusted for the following acts. Maybe it was both, but when a valiant Se quel guerrier io fossi! … Celeste Aida did not improve the mood of the willing public it was certainly not because of any inadequacy by the wonderful Italian tenor Marcello Giordani, who performed flawlessly the whole evening, so I have to presume that something in that act was missing out. If we exclude the music and the singers, we can only assume that a combination of excessive warmth in the theater and the staticity of the stage actions contributed to this unfortunate sensation of sleepiness that may have assaulted a few spectators. Exception to that was the scene in which they performed the quintet aria Alta cagion v’aduna that was so well balanced vocally and visually to have the effect of waking up any heavy-eyed spectator once and for all.

Thankfully, the Second Act was so thrilling it made up for that shortcoming and more, bringing back the opera to the expected and deserved all-around excellence that the Metropolitan got us used to.

The soprano Tamara Wilson, on her debut at the Met, was a tremendous Aida, finding tonalities that created a spectacular premise for the duets with the truly gifted mezzosoprano Violeta Urmana, who offered a convincing and full-bodied performance as Amneris. Her Fu la sorte dell’armi a’ tuoi funesta was so perfectly calibrated, both vocally and expressively, that Aida’s voice entered seamlessly and in an ideal singing duet, bringing joy to the adept listener as well as to the general audience.

The two basses were to say the least impressive. Dmitry Belosselskiy brought to life the high priest Ramfis forcefully and persuasively, and his voice was powerful while retaining a warmth in his vocal expression that was remarkably pleasant. Solomon Howard, as the Pharaoh of Egypt, was splendid, not so much for any particular acting, which was limited by the circumstances of his appearances, but because his superb voice had a booming but solid output while retaining a wonderful diction, which most often fades in the low notes of other basses’ performances.

To complete the wonderful performance of these singers was George Gagnidze as Amonasro, a baritone who has both the experience and the vocal capacity to carry this role. A delightful Rivedrai le foreste imbalsamate brought to life the ambiguity of the character who is more concerned with his revenge than with his daughter’s happiness.

Memorables the arias Qui Radamès verra .. O patria mia, sung in Act Three with heart and purity of voice by Tamara Wilson, and Morir! Si pura e bella, sung by Marcello Giordani with a touching but firm quality of voice at the end of Act Four.

It is without saying that the singers’ extraordinary performances were possible because of the outstanding work by the orchestra, conducted by a bold Marco Armiliato, and the chorus, directed by Donald Palumbo; their sensitive musical construction weaved a masterful background for the singers. Additionally, I found not without merit the dances, choreographed mightily by Alexei Ratmansky, which somehow lightened up a bit the gloomy tone of this unforgettable story.