Sviluppate dall’INGV nuove metodologie di osservazione dell’attività vulcanica a carattere esplosivo, grazie all’impiego di telecamere ad alta velocità e ad alta risoluzione. La ricerca è stata pubblicata su Geophisycs, Geochemistry, Geosystems e su Journal of Geophycal Research

Sperimentata per la prima volta una tecnica di ricostruzione delle esplosioni vulcaniche in 3D. A svilupparla, un gruppo di ricercatori del Laboratorio Alte Pressioni Alte Temperature di Geofisica e Vulcanologia sperimentali (HPHT) dell’Istituto Nazionale di Geofisica e Vulcanologia (INGV), grazie all’impiego di due telecamere ad alta velocità e ad alta risoluzione in modo sincronizzato. I risultati, pubblicati su Geophisycs, Geochemistry, Geosystems e su Journal of Geophysical Research, rappresentano un nuovo stimolo per migliorare le tecniche di monitoraggio applicate ai fenomeni esplosivi in aree attive ai fini della valutazione della pericolosità vulcanica.

“Il laboratorio HPHT”, afferma Piergiorgio Scarlato, responsabile della struttura, “è leader nello sviluppo di nuove metodologie applicate all’osservazione dell’attività vulcanica a carattere esplosivo, attraverso l’impiego di telecamere ad alta velocità e ad alta risoluzione. La collaborazione pluriennale con il Servizio Geologico degli Stati Uniti (USGS), l’Università di Hawaii e l’Università di Monaco di Baviera ha permesso di sviluppare e applicare queste nuove tecniche sull’Etna, Stromboli e su altri vulcani del mondo (Hawaii, Vanuatu, Indonesia), con il risultato di proporre un nuovo schema generale per classificare l’attività esplosiva a carattere stromboliano”.

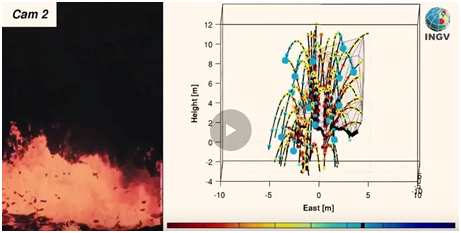

Con l’occasione è stata anche sperimentata, per la prima volta, una tecnica di ricostruzione delle esplosioni vulcaniche in 3D, utilizzando, nella ripresa delle eruzioni stesse, due telecamere ad alta velocità in modo sincronizzato.

“La recente attività esplosiva al vulcano Etna”, spiega Scarlato, “ha messo nuovamente in evidenza l’importanza di approfondire gli studi su questi fenomeni e di sviluppare tecniche osservative che consentano di raccogliere ogni informazione utile per la ricerca e il monitoraggio in questo ambito”. I sistemi di processamento al computer adottati, hanno permesso di analizzare ogni singolo pixel contenuto nelle migliaia di immagini raccolte, associando le riprese effettuate da due telecamere poste in due punti diversi di osservazione, fino a ottenere una ricostruzione tridimensionale degli eventi esplosivi filmati.

“Ciò ha permesso per la prima volta di determinare con precisione le traiettorie seguite dai prodotti emessi, la loro velocità e altri parametri aerodinamici fondamentali per modellare i processi eruttivi e l’area di dispersione dei prodotti attorno al cratere di emissione”, prosegue Scarlato.

La sperimentazione sui vulcani di queste nuove tecnologie ha richiesto diversi anni di sviluppo e di test portando a significativi risultati scientifici nel campo della Vulcanologia.

“Le informazioni raccolte aiutano a comprendere fenomeni eruttivi come quelli osservati all’Etna e Stromboli. In particolare, installando questi strumenti con particolari accorgimenti tecnici, è ora possibile misurare con precisione parametri eruttivi come la velocità di emissione dei prodotti piroclastici, il flusso di massa e le caratteristiche di dispersione dei prodotti nell’area circostante il cratere”, conclude Scarlato.

Abstracts

3-D high-speed imaging of volcanic bomb trajectory in basaltic explosive eruptions

Imaging, in general, and high speed imaging in particular are important emerging tools for the study of explosive volcanic eruptions. However, traditional 2-D video observations cannot measure volcanic ejecta motion toward and away from the camera, strongly hindering our capability to fully determine crucial hazard-related parameters such as explosion directionality and pyroclasts’ absolute velocity. In this paper, we use up to three synchronized high-speed cameras to reconstruct pyroclasts trajectories in three dimensions. Classical stereographic techniques are adapted to overcome the difficult observation conditions of active volcanic vents, including the large number of overlapping pyroclasts which may change shape in flight, variable lighting and clouding conditions, and lack of direct access to the target. In particular, we use a laser rangefinder to measure the geometry of the filming setup and manually track pyroclasts on the videos. This method reduces uncertainties to 108 in azimuth and dip angle of the pyroclasts, and down to 20% in the absolute velocity estimation. We demonstrate the potential of this approach by three examples: the development of an explosion at Stromboli, a bubble burst at Halema uma’u lava lake, and an in-flight collision between two bombs at Stromboli.

Integrating puffing and explosions in a general scheme for Strombolian-style activity

Strombolian eruptions are among the most common subaerial styles of explosive volcanism worldwide. Distinctive features of each volcano lead to a correspondingly wide range of variations of magnitude and erupted products, but most papers focus on a single type of event at a single volcano. Here, in order to emphasize the common features underlying this diversity of styles, we scrutinize a database from 35 different erupting vents, including 21 thermal infrared videos from Stromboli (Italy), Etna (Italy), Yasur (Vanuatu), and Batu Tara (Indonesia), from puffing, through rapid explosions to normal explosions, with variable ejection parameters and relative abundance of gas, ash, and bombs. Using field observations and high-speed thermal infrared videos processed by a new algorithm, we identify the distinguishing characteristics of each type of activity and how they may relate and interact. In particular, we record that ash-poor normal explosions may be preceded and followed by the onset or the increase of the puffing activity, while ash-rich explosions are emergent, i.e., with inflation of the free surface followed directly by emission of increasingly large gas pockets. Overall, we see that all Strombolian activities form a continuum arising from a common mechanism and are modulated by the combination of two well-established controls: (1) the length of the bursting gas pocket with respect to the vent diameter and (2) the presence and thickness of a high-viscosity layer in the uppermost part of the volcanic conduit.