By Frances R. Curcio

The Last Stops on the Around-the-World Tour: Serengeti National Wildlife Refuge, Tanzania; Luxor and Cairo, Egypt; and Marrakech, Morocco

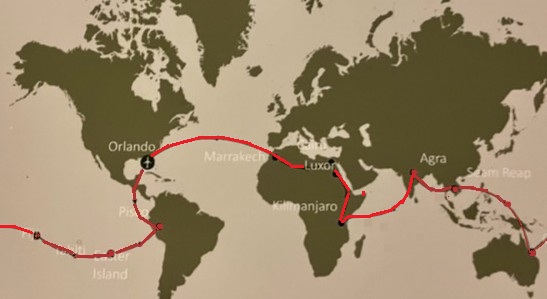

After two weeks and six stops (Machu Picchu, Rapa Nui, Fiji, The Great Barrier Reef, Angkor Wat, and The Taj Mahal), my travel companions and I continued to complete the 28,105 miles around the world in a TCS World Travel jet. Our last four stops were Serengeti National Park, Luxor and Cairo, and Marrakech. These sites have been recognized as World Heritage Sites by UNESCO. The first is one of the most beautiful natural habitats in the world, and the others have been recognized as historical and cultural treasures.

SERENGETI NATIONAL PARK, TANZANIA

The park has been a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 1981, and it was established in 1940. It stretches over 5,700 square miles, providing a habitat for many varieties of wildlife and flora. The Park is home to over two million ungulates (i.e., hoofed mammals), 4,000 lions, 1,000 leopards, 225 cheetahs, 2,700 elephants, 70,000 buffalos, 4,000 giraffes, 300,000 zebras, 15,000 warthogs, 500 hippopotamuses, 200 black rhinoceros, 10 species of antelope, about 500 species of birds, and many more herbivores and carnivores. I was overwhelmed with excitement to be among the animals in a safe, protected vehicle. The first animals I encountered were lions while we were en route to the hot air balloon launch site.

While we were in the hot air balloon, we were able to survey the wildlife at an elevation of about 1,500 feet. We covered about 15.6 miles in about 2 hours. It was a truly exhilarating, “high-flying” experience.

During our daily game drives through the rough terrain, my travel friends and I stayed with our outstanding driver and guide, Reggie. He was extremely knowledgeable. He described the flora and fauna as we surveyed the area, and he answered our many questions.

From the road, we were able to see giraffes. Reggie told us that a giraffe’s heart weighs about 11 to 15 kg, or about 25 to 33 pounds, accounting for 0.5% of its total body weight. In comparison, a human heart weighs between 0.66 to 1.1 pounds.

We also encountered many zebras. While we were driving, a herd of zebras decided to cross the road and Reggie respectfully stopped for a few minutes until they all reached their destination.

Along the road, we encountered herds of impalas. I thought they were deer, but Reggie explained that they were impalas which belong to the same family, Cervidae. Impalas are smaller in size than deer. I learned that a difference between impalas and deer is that male deer have antlers that they shed and regrow annually.

Reminiscent of feeding an elephant in Cambodia, I had the chance to see a herd of elephants grazing in a field. We did not get too close to them. We stayed in the jeep.

I had never seen an African buffalo before, and there were plenty of them in Serengeti! As Reggie described this animal, I learned the term “ungulate,” as he referred to the even-toed horned animal, which is related to the antelope, cattle, goat, and sheep. We learned that the zebra is a single-hoofed ungulate. It was eerie when the buffalo looked at us, probably getting ready to protect its turf. I was glad to be safe in the fortified jeep.

The setting of the lodge where we stayed was ecologically designed to blend in with the natural habitat. As a result, in the late evenings and early mornings, animals roam around freely and armed security guards escort the guests to the various activities on the property and back to their lodgings. Each comfortable room had an outdoor porch with sliding doors containing a security lock. To avoid being “visited and greeted” by a wild animal or two, we were instructed not to leave the sliding doors open at night and not to step out into the fields in the dark. You can be sure that my sliding door was always locked!

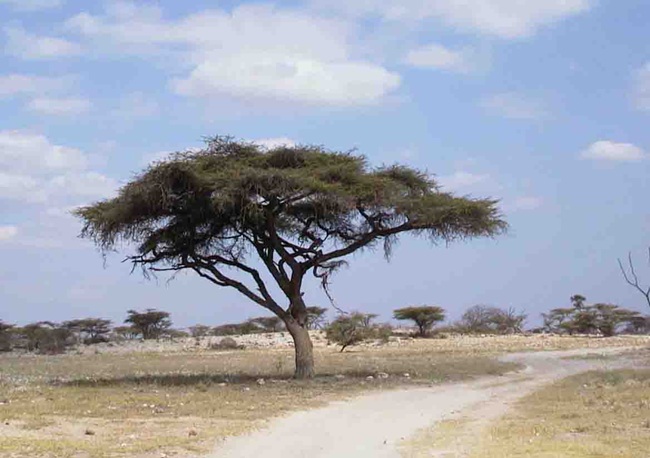

As we drove through the Park, in addition to learning about the animals that we encountered, we also learned about various trees and birds. In particular, we noticed many Whistle Thorn trees, and one variety of Acacia trees, which are the symbol of Africa.

Endemic to Africa, the Secretary Bird is a bird of prey. In search of prey, the bird can cover over 18.6 miles a day searching for snakes, insects, and various animals. During our safari we witnessed many of these birds hunting for their meals.

Although I have visited the Staten Island Zoo, the Bronx Zoo, the San Diego Zoo, the New York Botanical Gardens, and Longwood Gardens many times, the animals in the zoos were always enclosed in cages, and the plants were on display in their simulated environments. Experiencing the fauna and flora in the “wild” was beyond my “wildest” dreams! Being in a protective environment but yet able to be with the animals and watch their “body language,” as they encountered other animals and inquisitive visitors (i.e., us) in our jeeps, was thrilling.

A potential threat to the animals in their natural habitat is the lack of sufficient surface water during the dry season, from May to October. The only permanent source of water is from the Mara River in the north, which supports the migrating animals. From May to August, the Serengeti National Park experiences a generally cool, dry season. From September to October, the park experiences a dry, warmer season. From November to April, the park experiences a wetter, hotter season. Due to “the growing demands on limited water sources” (Ministry of Water, 2020, p. ii), plans have been underway to develop a water allocation system to support the environmental needs of the region and to support the survival of the many varieties of the flora and fauna in the region.

Throughout our stay in Serengeti, I heard the Swahili term, “Hakuna Mata,” a familiar phrase from the Disney film The Lion King. It became part of my vocabulary when I wanted to respond politely with “no trouble” or “no worries.”

LUXOR AND CAIRO, EGYPT

My visit to Egypt was the fulfillment of a life-long dream. In school I recall studying about the many contributions and advances that the Egyptians made in science, mathematics, engineering, and other scholarly fields. The two stops, Luxor and Cairo, were enough to whet my appetite and motivate me to begin to plan to return.

Our first stop in Egypt was Luxor. We arrived in the early evening and our first visit was to the Luxor Temple complex, designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1979. Our knowledgeable guide, Mr. Mohamad Eissa, made the monuments and the historical facts “come alive.” He helped us to develop critical eyes as we examined artifacts in the field.

Luxor Temple is known as the “southern sanctuary,” located on the east bank of the Nile River. Construction was started in 1400 BCE, during the reign of Amenhotep III, and completed by Tutankhamun (i.e., King Tut). This era was the New Kingdom Period, the peak of the Egyptian Empire. As a center for religious rituals and festivals, the Temple was dedicated to the Theban triad of gods– Amun, Mut, and their son Khonsu.

I recall seeing the King Tutankhamun (AKA King Tut) exhibit when it arrived in New York City at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in November 1976. The extensive exhibit was on display until September 1979. The museum catalogue (Gilbert, Holt, and Hudson, 1976) that I bought when I visited the exhibit in New York, helped me to prepare for the visit to the Valley of the Kings in Luxor. Viewing the well-preserved remains of King Tut, the famous pharaoh of the 18th dynasty of ancient Egypt, brought back vivid memories from almost fifty years ago! This time I was able to get a very close look at King Tut’s preserved face.

During our morning in Luxor, we visited several temples—Karnak, Khonsu, among others.

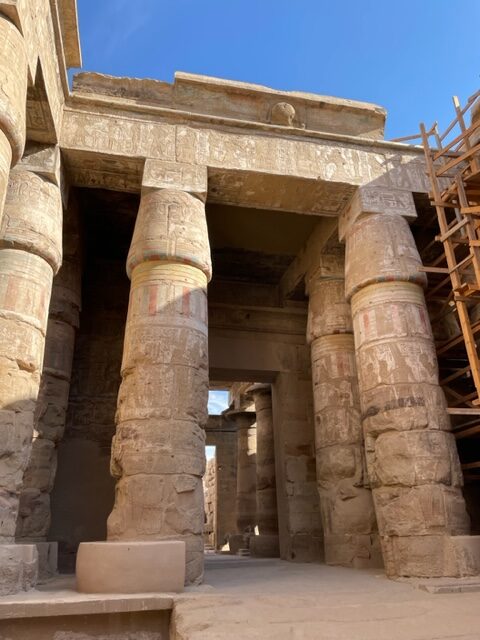

Karnak is composed of a complex of temples, chapels, and pylons (i.e., gateways adorned with monuments), built from about 2055 BC through 100 AD, to honor the gods Amun, Mut, and Khonsu. Located in the heart of the Temple of Karnak, the Gateway of Euergetes is an example of Egypt’s Ptolemaic period.

Khonsu Temple is part of the complex of Karnak Temple. It was built by King Rameses III, from 1186-1155 BC, to honor the moon god, Khonsu, the son of Amun-Re and Mut.

To visit the Pyramids of Giza and the Great Sphinx, all part of the UNESCO World Heritage Site and recognized as such in 1979, we boarded our private jet for a 1.25-hour plane ride. Expecting to become gods in the afterlife, the pharaohs built pyramids to store and preserve everything they believed they would need.

Located on the Giza plateau not far from Cairo, the Great Pyramid of Giza, was built over a twenty-year. It was the largest in the world when it was built during the reign of King Khufu (2589-2566 BCE). It is the only surviving Wonder of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World.

After a luncheon cruise on the Nile River, the longest river in the world, we boarded our jet and flew to Cairo. When we arrived to see the Great Sphinx, we were addressed by Dr. Mustafa Waziri, the former director of the Supreme Council of Antiquities. He described the many efforts to be undertaken to preserve and restore the structures and maintain the many artifacts.

Carved from a single piece of limestone, the Great Sphinx has the face of a man and the body of a lion. It is estimated that it took about 100 workers about 3 years to build. Although it is thought to be the best example of sphinx art, it has been questioned what this megalith signifies. It is believed that since it has a face resembling Pharaoh Khafre, it is believed that it was built for him in about 2500 BCE. It has influenced the imaginations of poets (e.g., Brownell, 1866; Emerson, 1841), studies by scientists (Boury et al., 2023; Orf, 2023), and the interests of inquisitive travelers like me.

We were given the wonderful opportunity to pose between the feet of the Great Sphinx. It was thrilling to be in an actual historical artifact—even for just a moment!

MARRAKECH, MOROCCO

Edith Wharton visited Morocco in September 1917, when it was French Morocco. The world was in turmoil during the fourth and last year of WW I. Her clever work of propaganda and social and historical commentary, In Morocco, was published in 1919. Visiting the country through her eyes is a great contrast to what we experienced 108 years later. Since gaining independence from France in 1956, the economy has been thriving, and travelers are welcomed. Our last visit on our around-the-world journey was to Marrakech, deemed a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1985.

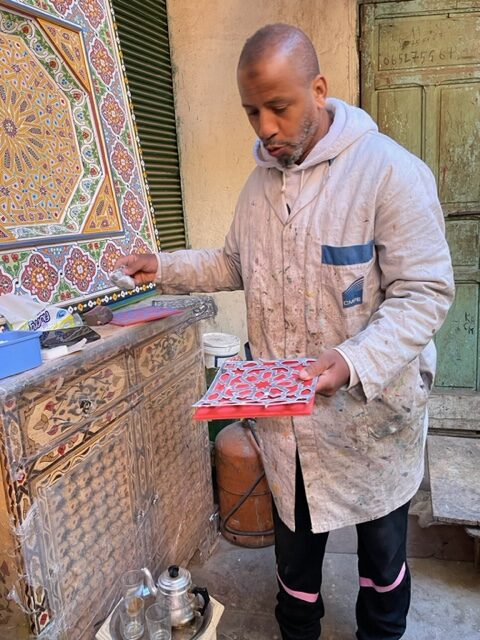

Although we were with our guide, Zohair, passing through the Medina Quarter, which dates to the 11th C, it felt as though we were back in time, walking through a meandering labyrinth. With the help of our guide, we saw for ourselves examples of extraordinary craftsmanship. He pointed out how the architecture reveals a melding of Islamic and Spanish styles, with Amazigh designs characterized by open courtyards and beautiful gardens. We spent time in the souk (i.e., Arab marketplace) in the Medina Quarter to observe the workers and craftsmen demonstrating their craft and the effort of their labor.

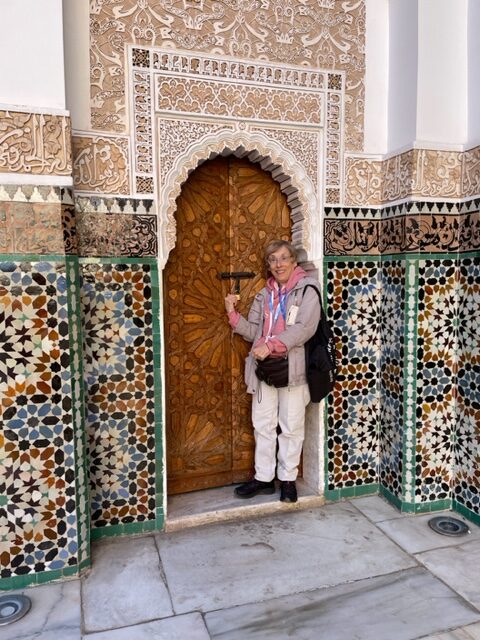

One of our stops was at the Madrasa Ben Youssef, Koranic School, founded in14th C and expanded in the 16th C. Built with marble and carved stucco during the reign of Sultan Abdellah Al Ghalib, with 138 rooms. In 1564, it is recorded that it accommodated as many 900 students. Studies in mathematics and astronomy were emphasized. Today it is a major tourist attraction.

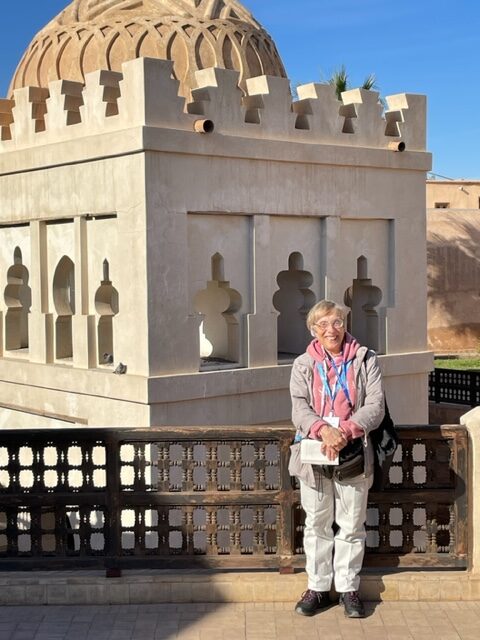

Not too far from the Ben Youssef Koranic School, is the oldest monument in Marrakech, the Almoravid Koubba. Built in the 12th Century, It was originally a place for Muslim worship and then used as a mausoleum for Almohad leaders. It is the only surviving example of exquisite Almoravid Architecture.

Closing Comments

When the journey came to an end, it was difficult to “land” from such an amazing, whirlwind adventure! I must say that in some situations (e.g., Serengeti, India, Cambodia), I was definitely out of my comfort zone. The animals in the wild in Serengeti, the crowds and confusion in India, and the unique foods and customs in Cambodia were all, at times, overwhelming. But experiences at each stop contributed to developing an understanding and appreciation for people who live in settings that are worlds away from my little, limited corner of the earth. They all occupy a special place in my heart. Each of the nine wonderful settings had its special characteristics to take away—the sights created images that are now embedded in my memory; the sounds that were unfamiliar, but yet enticing, continue to echo in my ears; the smells and aromas that were shocking and sweet awakened my olfactory nerves; and the flavors that attacked and soothed my taste buds, have educated my palate. In closing, as I reflect on the many people, places, and experiences encountered, Edith Wharton summarizes them eloquently, “And how can it [all] seem other than a dream?” (1920, p. 157).

References

Boury, Samuel, Scott Weady, & Leif Ristroph. Sculpting the Sphinx. Physical Review Fluids, 8, 110503, 2023. https://journals.aps.org/prfluids/pdf/10.1103/PhysRevFluids.8.110503

Brownell, Henry Howard. “The Sphinx.” In War-Lyrics, and Other Poems, Cambridge

University Press, Welch, Bigelow, & Co., 1866, p. 189-192.

http://www.poetryatlas.com/poetry/poem/4472/the-sphinx.html

El-Baz, F. 1981. “Desert Builders Knew a Good Thing When They Saw It.” Smithsonian, 12, 116–122.

Gilbert, Katharine Stoddert, with Joan K. Holt, and Sara Hudson. Treasures of King Tutankhamun. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1976.

Serengeti National Park. UNESCO World Heritage Convention.

https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/156

Discovering the Enchanting History of Luxor Temple: A Guide to Its Facts and Secrets.

https://www.aroundegypttours.com/egypt-tourist/luxor-tourist-attractions/luxor-temple

Emerson, Ralph Waldo. “The Sphinx.” The Dial, Vol.1, No. 3, January, 1841.

https://www.walden.org/sub-work/rwemerson-the-dial-jan-1841-the-sphinx/

Lee, Hermione. Edith Wharton. New York: Vintage Books, 2007.

Orf, Darren. “A New Study Reveals the Astonishing Way the Great Sphinx in Egypt Actually Formed.” Popular Mechanics, October 30, 2023.

https://www.popularmechanics.com/science/archaeology/a45668353/how-did-great-sphinx-in-egypt-form/

Reeves, Nicholas, and Richard H. Wilkinson. The Complete Valley of the Kings: Tombs and Treasures of Egypt’s Greatest Pharaohs. London: Thames and Hudson, 1996.

“Tut-ankh-Amen Died While Still a Boy, His Tomb Discloses.” The New York Times, 7 February 1923, pp. 1, 3.

Water Allocation Plan for the Mara River Catchment, Tanzania. Ministry of Water, The United Republic of Tanzania, March 2020. https://nilebasin.org/sites/default/files/2024-10/Water%20Allocation%20Plan%20WAP_Mara%20River_%203-29-2020.pdf

“Weather and Climate in Serengeti National Park.” Focus East Africa Tours. https://wildlifesafaritanzania.com/weather-and-climate-in-serengeti-national-park/

Wharton, Edith. In Morocco. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1920.

York, Jillian C. Morocco: The Essential Guide to Customs & Culture. Great Britain: Kuperard, 2023.

Zouiten, Sarag. “Morocco’s Economy Poised for Recovery in 2025 with Boosts in Industry, Agriculture,” 20 Jan 2025. https://www.moroccoworldnews.com/2025/01/165654/moroccos-economy-poised-for-recovery-in-2025-with-boosts-in-industry-agriculture/