Reviewed by LindaAnn LoSchiavo for L’Idea

Born in Bergamo, Italy, Paola Loreto teaches American Literature at the University of Milan. A distinguished author of five poetry collections, she also maintains a robust presence in literary journals and magazines; look for her free verse in Poesia, L’Almanacco dello Specchio Mondadori, La Mosca di Milano, ClanDestino, Ciminiera Il segnale, La colpa di scrivere, and others. Americans can enjoy a selection of her verses, posted in English, at Kritya.in.

Prof. Loreto has been crowned with laurels, earning the enviable acclaim bestowed by Tronto, Benedetto Croce, Calabria-Alto Ionio, un fiore di parola, Alpi Apuane, Antonio Fogazzaro, San Vito al Tagliamento, and the Premio Umbertide. The judging panel of the Subway-Poesia Prize includes her name.

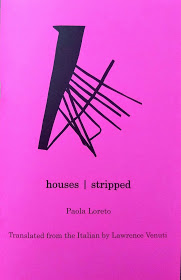

Thanks to her translations, Italians have become better acquainted with the poetry of Richard Wilbur, A.R Ammons, Philip Levine, Derek Walcott, Charles Simic, Amy Newman, and Emily Dickinson, whose influence is apparent in Loreto’s bi-lingual chapbook “houses | stripped” [Toad Press, 2019], translated into English by Lawrence Venuti.

Traduttore, traditore: Translator, traitor

Though the versatile and venerable Venuti has done a credible job here, sometimes I disagreed with his interpretations.

Take this line by Loreto, for example: “Una casa è dove / non fai rumore.” Venuti translates it: “A house is wherever / you mustn’t make a sound.”

But I read it as “A house is wherever / you don’t make noise” because the disruptive noun “noise” carries enough weight to be “la pagina che volta / una vita ignara” than the more cautious noun “sound,” whose soft sibilant “s” seems to run contrary to Loreto’s deliberate cacophony of hard c-sounds: casa, corpo, occhi, che, nocca, perché, and especially in the poem’s final imperative: “Ascoltami.”

However, here’s the translation that puzzled me the most: “Non importa se non arrivo / da nessuna parte se il mio fare / è vano. Ero dentro il mondo. / Non finisco l’esperienza . . . . Venuti translates it: “Never mind if I don’t come / from anywhere if my building / is vain. I was inside the world. / I don’t put paid / to the experiment . . . .

But I read her Italian lines as “It doesn’t matter if I don’t get / anywhere if my doing / is in vain. I was inside the world. / I don’t finish the experience . . . To me, “my doing” seems organic while Venuti’s interpretation as “my building” sounds harsher and more specific. Also, I read “l’esperienza” as the experience — — not the experiment.

Occasionally, the Italian language seems to defy translation entirely. Loreto writes: “La nostra casa è rimasta / nel sogno. Noi siamo usciti. / Siamo qui. Siamo. Venuti translates it: “Our house remained / a dream. We left. / We’re here. We are.” And though he is perfectly correct, the English translation includes no words that begin with “s.” In contrast, Loreto’s Italian version is as light as a souffle with its insistent repetition of “siamo,” its soothing sibilants musically in harmony with “sogno” and also the “s” heard in “nostra,” “rimasta,” and “usciti.”

This collection contains 21 poems, none longer than 18 lines, and the first curtsy to the Belle of Amherst is that both writers decided to dispense with titles; to choose plain, unadorned language; and to rely on short lines.

Characterizing Dickinson’s Poetry

In case our L’IDEA readers are unfamiliar with Dickinson’s poetry, the Poetry Foundation set forth an analysis: “Emily experimented with expression in order to free it from conventional restraints. Like writers such as Charlotte Brontë and Elizabeth Barrett Browning, she crafted a new type of persona for the first person. The speakers in Dickinson’s poetry, like those in Brontë’s and Browning’s works, are sharp-sighted observers who see the inescapable limitations of their societies as well as their imagined and imaginable escapes. To make the abstract tangible, to define meaning without confining it, to inhabit a house that never became a prison, Dickinson created in her writing a distinctively elliptical language for expressing what was possible but not yet realized.”

I sense such a distinct yearning for “expressing what was possible but not yet realized” in these four lines by Paola Loreto (page 12):

Perché è impossible sapere /

e immaginare e letale. /

Lascia che il possibile sia /

figlio del reale, della roccia. . . .

Throughout her spartan chapbook, her untitled, spare, and simply-worded poems evoke cycles of life and the human longing for meaning and connection. These poems, often repeating “casa” [“house”], open the mind to matters beyond the quotidian, ferrying observations past their obvious conclusions and resonating with deep — — though sometimes imprecise — — feelings.

Before writing my review, I recited the book aloud in order to play Loreto’s language music in my head. Throughout this collection, her lullaby of sibilants became a sostenuto. Where the Italian text glides, its English approximation can only rap, betraying its composer. Her writing is meant to be enjoyed in Italian.

* * *

Order this chapbook at Toad Press’s site:

https://toadpress.blogspot.com/2018/08/houses-stripped.html?m=1

Visit Paola Loreto’s site: https://sites.google.com/site/paolamarialoreto/bio