When I reached 40 years of age, I started to witness changes in physical appearance, marital status and even death of those around me. These transformations gave me the impetus to act on a desire that went unfulfilled too long — to visit Molfetta, the land of my parents. I also wished to meet my father’s relatives for the first time. I was advised that September and Easter time was the best time to visit.

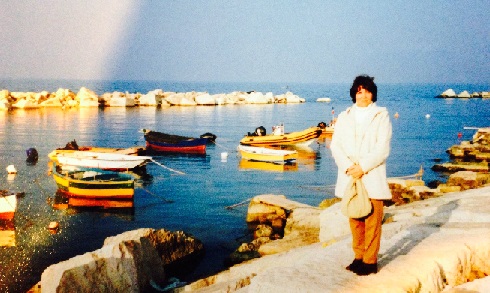

By plane, it’s 40 minutes southeast of Rome on the coast of Apulia, an area which dates back to the fifth millennia B.C. I flew directly to Bari, the regional capital, which was only a twenty-minute drive from Molfetta. This province lies along the Adriatic Sea from the heel of Italy up to the Gargano Peninsula. On a clear day, from their harbor, Molfettesi can see Monte Gargano, which is 50 miles away.

By plane, it’s 40 minutes southeast of Rome on the coast of Apulia, an area which dates back to the fifth millennia B.C. I flew directly to Bari, the regional capital, which was only a twenty-minute drive from Molfetta. This province lies along the Adriatic Sea from the heel of Italy up to the Gargano Peninsula. On a clear day, from their harbor, Molfettesi can see Monte Gargano, which is 50 miles away.

Monte Gargano, a sacred place, is a dark limestone peninsula that dramatically juts 40 miles out into the azure sea. There one finds a shrine in honor of St. Michael the Archangel in the cave where he was said to have appeared dressed in full armor. For over 1,500 years, pilgrims from all over Europe have prayed at this shrine.

If the Norman crusader, Robert Guiscard, had not stopped on Christmas Day in 1016 to give thanks to St. Michael for defeating the Lombards, the course of southern Italian history, with its subsequent Norman invasion might never have taken place; the Molfettesi and Apulia would not have been permanently infused with Norman blood.

If the Norman crusader, Robert Guiscard, had not stopped on Christmas Day in 1016 to give thanks to St. Michael for defeating the Lombards, the course of southern Italian history, with its subsequent Norman invasion might never have taken place; the Molfettesi and Apulia would not have been permanently infused with Norman blood.

As my plane flew by Monte Gargano, I saw a varying landscape of wheat fields, vineyards, and olive groves woven into a patchwork of beautiful green, yellow and brown rectangles and squares. Then the medieval cities of stone carved into the mountains and bordering the coastline came into view. My heart began to race as I realized one of the towns along the water was my final destination — Molfetta.

Upon arriving I was met by two septuagenarians. I knew from the pictures they were my Aunt Maria and Uncle Torino, my father’s first cousins. “Elisabetta?” they asked. The welcoming began in earnest with hugs and kisses and introductions to their children, Rosa, Anna and Lorenzo, my contemporaries. They took my bags and led the way to the parking lot. When I inquired about clearing customs they just shrugged and said in dialect–“sci me ninne” or “let’s go.” This was ten years before September 11th, so we got away with it.

Upon arriving I was met by two septuagenarians. I knew from the pictures they were my Aunt Maria and Uncle Torino, my father’s first cousins. “Elisabetta?” they asked. The welcoming began in earnest with hugs and kisses and introductions to their children, Rosa, Anna and Lorenzo, my contemporaries. They took my bags and led the way to the parking lot. When I inquired about clearing customs they just shrugged and said in dialect–“sci me ninne” or “let’s go.” This was ten years before September 11th, so we got away with it.

Northward we drove through farmlands with centuries old vineyards, and groves of straining, contorted and knobby olive trees. We also passed two unusual structures that piqued my curiosity – the pagliaros and towers. Ancient stone observation towers intermittently dot the countryside along the highway. I later learned that for centuries the inhabitants of these stone sentinels had monitored the sea for the invading hordes of Greeks, Romans, Lombards, Normans, Saracens, Spanish, French and Venetians. Using bells by day and lighting torches by night, these observation towers could efficiently signal a message down the coast, around the heel and toe to Sicily. Though time and the elements have systematically eroded most of the towers along the coast down to their skeletal shells, at least thirty unique towers exist in the immediate environs of Molfetta.

The other structure dotting the landscape was the pagliaro. It is a short, stout, circular stone barn with a thatched roof, one doorway and no windows. Crops and farming implements are stored there.

Once we reached the sea we found ourselves outside the walls of Molfetta Vecchia, “Old Molfetta”. Now this was the Molfetta I had heard about! This historic district, which was called Respa, Melphi and Melficta at various times in its history, predates the ninth century. Legend says that the town was founded by Ulysses on a tiny island called San Andrea which was barely off the mainland. Though its true origin cannot be proven with certainty, Molfetta is a city with strong Greek roots as two temples in honor of Neptune and Diana are said to have existed there.

Once we reached the sea we found ourselves outside the walls of Molfetta Vecchia, “Old Molfetta”. Now this was the Molfetta I had heard about! This historic district, which was called Respa, Melphi and Melficta at various times in its history, predates the ninth century. Legend says that the town was founded by Ulysses on a tiny island called San Andrea which was barely off the mainland. Though its true origin cannot be proven with certainty, Molfetta is a city with strong Greek roots as two temples in honor of Neptune and Diana are said to have existed there.

In 1025, Molfetta was the episcopal seat and home to a feisty Norman knight name Jocelyn, Lord of Molfetta. The tall, blond Jocelin was the typical Norman knight – notorious for being a lawless liar who committed rape, robbery, blackmail and murder. Jocelyn acquired Molfetta as payment for services rendered to Robert Guiscard. As his vassal he assisted Guiscard with the Norman takeover of Apulia. The towns along the coast, such as Molfetta, Trani and Bari, had been part of the Magna Grecia for centuries. Later Jocelin found that the Greeks paid even more handsomely. He changed loyalties and lead many an insurrection against the Normans. For this he was given the Dukedom of Corinth in Greece and the designation of “archenemy” of Guiscard.

Robert Guiscard, on the other hand, was a quick-witted, eclectic military genius who started from nothing and died undefeated. In 1071, he finally wrestled complete control of Bari, the Greek capital, and the coastal towns, such as Molfetta, away from Jocelyn, and his Greek benefactors. Jocelyn was never heard of again, but Guiscard’s descendants prospered and one, Frederick II, became the Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire. One of his castles, Castel del Monte, is near Molfetta.

Now that the Normans ruled, a cathedral, il Duomo di Molfetta, was commissioned to be built in the exact location where a Greek temple in honor of Neptune was believed to have stood. The cathedral, dedicated to St. Mary Assumed into Heaven, was completed in the 13th century.

Now that the Normans ruled, a cathedral, il Duomo di Molfetta, was commissioned to be built in the exact location where a Greek temple in honor of Neptune was believed to have stood. The cathedral, dedicated to St. Mary Assumed into Heaven, was completed in the 13th century.

This massive edifice, exemplifying Romanesque-Pugliese architecture, is an Italian historic landmark. It has three cupolas centered over the nave, two slender towers and bare, stone walls which are strikingly stark, yet beautifully solemn. It is much more reminiscent of a Norman castle than an Italian cathedral. It was one of the only parishes in Molfetta until a 16th century Baroque cathedral, which usurped its name, was built. The old Church was then given a new name, that of the Church of St. Conrad. Today, most people call the Duomo “La Chiesa Vecchia”, the old church.

Old Molfetta, with its Duomo, stood on an island which was totally surrounded by thick stone walls and a massive tower built by the Passari family. These walls served as protection against marauders and as a sea wall that, in inclement weather, bore the brunt of the crashing waves. Centuries later, the western side of the island was filled in and connected with the mainland, creating a wide street now called Via Dante.

Lying just outside the old quarter, near a harbor bustling with merchants, ships and people embarking and disembarking, vibrant Via Dante and its piazza was considered Molfetta’s “pulsating heart.” Today, this area boasts of many shops, businesses and cafes where people congregate regularly as well as a Baroque Cathedral and plenty of twentieth century vehicular traffic.

Lying just outside the old quarter, near a harbor bustling with merchants, ships and people embarking and disembarking, vibrant Via Dante and its piazza was considered Molfetta’s “pulsating heart.” Today, this area boasts of many shops, businesses and cafes where people congregate regularly as well as a Baroque Cathedral and plenty of twentieth century vehicular traffic.

This street is in direct contrast to the shadowy streets within the walls. Inside the sparsely populated Molfetta Vecchia, the silent and narrow twisting streets resemble a deserted Arabian casbah, having only three small entrances. Molfetta Vecchia is called in dialect “ind’alla terre” which means “in the ground”. One theory for this term relates to the description of what occurred when invaders entered the walls. It was as if they were swallowed up by the ground. The encroachers would enter the confusingly winding streets only to find themselves disoriented and trapped when they were attacked from the rooftops of the two and three-story buildings.

Walking the hushed and deserted stone streets of Molfetta Vecchia, I tried to imagine the once bustling tiny city crammed with 6,500 residents. Peering down shadowy lanes, I remembered my father saying that cold, stormy winter winds carried the echo of the waves over the walls and into town. Once inside it reverberate against the stone houses creating an ominous and continuous groan. On Via Amente my relatives showed me the building my great-grandfather, a wainwright, had his shop.

Walking the hushed and deserted stone streets of Molfetta Vecchia, I tried to imagine the once bustling tiny city crammed with 6,500 residents. Peering down shadowy lanes, I remembered my father saying that cold, stormy winter winds carried the echo of the waves over the walls and into town. Once inside it reverberate against the stone houses creating an ominous and continuous groan. On Via Amente my relatives showed me the building my great-grandfather, a wainwright, had his shop.

Some of “Molfetta Vecchia” stands by virtue of the wooden harnesses holding up the walls of the buildings. The rehabilitated sections have beautiful wooden doors and new iron balconies and plaques identifying a noble residence or municipal building and the date. Here I saw the first sign of Easter with flowers filling the balconies. Little by little people are returning to live in the rehabilitated buildings. They have even converted a large residence on the water into a luxurious bed and breakfast. The sections that are barely livable are inhabited by African and Albanian squatters.

Surrounding the town on three sides is modern Molfetta. I use the world “modern” loosely, as one neighborhood such as the “Camere Nuove” dates back to the 16th century. Each of the new divisions has its own unique style, beautiful balconies filled with plants and flowers and shutters. Almost every building in the town has green shutters.

“Modern Molfetta” has many churches and chapels of varying sizes and styles, such as Romanesque-Pugliese, Neoclassic, Baroque, Gothic, Iconic-Greek, Early and late Renaissance and Modern. These churches are filled with lifelike statues, frescos, tapestries and paintings done by local as well as European artists. I was told that since it was Easter Thursday, we would be visiting many churches and each one would be filled with beautiful floral arrangements and statues that would be used in the Easter procession that was coming up.

After the noon dinner and a little rest, we explored the “Camere Nuove,” which means the “new rooms.” My father was born there and it was one of the first housing developments built outside the walls of Molfetta Vecchia. The buildings of dingy peach color were built from blocks of stone carved out of a local mountain of tufa rock. Over 600 years ago, the inhabitants of this area lived in tufa rock caves. In remembrance of this, this section is sometimes referred to as the “catacombs” even though the “catacombs” have been gone for a very long time.

After the noon dinner and a little rest, we explored the “Camere Nuove,” which means the “new rooms.” My father was born there and it was one of the first housing developments built outside the walls of Molfetta Vecchia. The buildings of dingy peach color were built from blocks of stone carved out of a local mountain of tufa rock. Over 600 years ago, the inhabitants of this area lived in tufa rock caves. In remembrance of this, this section is sometimes referred to as the “catacombs” even though the “catacombs” have been gone for a very long time.

We passed my father’s birthplace, 25 Via Sigismondo, a winding cobblestone street whose streets were as narrow as those in Molfetta Vecchia. Down the lane was great-grandfather’s apartment, which was on the ground floor. I was overcome with emotion just looking at the buildings.

This neighborhood would be visited by the solemn Easter procession depicting the Stations of the Cross. The procession involved hundreds of people and I learned is very stratified socially. The men wore costumes that looked like KKK garb in white and in different colors. Each color denoted the social status and the role in the procession. For instance, the Confraternity of St. Stephen was composed of the upper echelon of the town’s society. They wore black and it was also called the Confraternity of Death because they carried the statue of the dead Jesus.

This neighborhood would be visited by the solemn Easter procession depicting the Stations of the Cross. The procession involved hundreds of people and I learned is very stratified socially. The men wore costumes that looked like KKK garb in white and in different colors. Each color denoted the social status and the role in the procession. For instance, the Confraternity of St. Stephen was composed of the upper echelon of the town’s society. They wore black and it was also called the Confraternity of Death because they carried the statue of the dead Jesus.

The men retrieve the statues for the Stations of the Cross and walk the lanes of the town for eight hours before they are returned to their respective churches. This is a real labor of love for these men, they take their job very seriously and offer up their discomfort. The men were dressed in black, white with red trim, red, brown, orange. Each color represented a fraternity and church.

Men women and children gather along the route to listen to brass band that plays throughout the entire route. People pray, some cry at seeing the bruised body of Jesus, other cry for Mary his mother. Children are dressed as people from the bible at Easter from a very young age and often follow along for awhile, especially if their father is one of the cloaked participants. My father was partial to his John the Baptist costume when he was a little boy. Since his paternal grand-father was Chief of Police and the other one was a renowned business man, who made coaches and wagons for the rich, traveling to Austria for the wood for his vehicles, they were part of the Confraternity of Death.

On Easter Sunday, the piazza’s and balconies around town were bursting with flowers and Palm Crosses and the bakery windows were filled with baked goods such as the ‘La Colomba Pasquale,’ the Easter Dove, and chocolate eggs and bunnies of every size.

The Easter dinner has its different entrees, but with portions modestly sized. Dinner in my aunt’s house consisted of antipasto of cured meats and marinated or fried vegetables, such as artichoke hearts, fresh fennel, mushrooms. Next came lasagna, made with homemade pasta sheets that were light and with the meat and ricotta filling not densely packed. The last entrée was the traditional ‘Agnello Benedetto.’ This was a roasted lamb stew, which had a layer of beaten eggs added at the very end of cooking. Besides the fruit and nuts for dessert, traditional Easter specialties were served.

The Easter dinner has its different entrees, but with portions modestly sized. Dinner in my aunt’s house consisted of antipasto of cured meats and marinated or fried vegetables, such as artichoke hearts, fresh fennel, mushrooms. Next came lasagna, made with homemade pasta sheets that were light and with the meat and ricotta filling not densely packed. The last entrée was the traditional ‘Agnello Benedetto.’ This was a roasted lamb stew, which had a layer of beaten eggs added at the very end of cooking. Besides the fruit and nuts for dessert, traditional Easter specialties were served.

At this point the neighbors from across the hall came over and ‘la scarchedde,’ one in the shape of an egg and one in the shape of a heart were served. These flaky pie-like cakes were filled with preserves, orange in one and fig in the other. Then the chocolate desserts appeared: ‘la colomba pasquale,’ and Easter eggs, chocolate eggs of varying sized contained a little gift. The neighbor gave his wife a beautifully decorated egg and when she cracked its shell, a gold bracelet appeared. Most of the time, it had prizes similar to the CrackerJack prizes – just something to laugh about, unless there was an occasion nearing, such as an anniversary, birthday etc.

At this point the neighbors from across the hall came over and ‘la scarchedde,’ one in the shape of an egg and one in the shape of a heart were served. These flaky pie-like cakes were filled with preserves, orange in one and fig in the other. Then the chocolate desserts appeared: ‘la colomba pasquale,’ and Easter eggs, chocolate eggs of varying sized contained a little gift. The neighbor gave his wife a beautifully decorated egg and when she cracked its shell, a gold bracelet appeared. Most of the time, it had prizes similar to the CrackerJack prizes – just something to laugh about, unless there was an occasion nearing, such as an anniversary, birthday etc.

Uncle Torino passed away recently and I know their Easter this year will be very somber. I have very fond memories of my aunt and uncle and the three cousins. They made every effort to show me Molfetta and its environs. I have been there since, but there is nothing like the first time you become acquainted with your family history and the life your great-grandparents, grandparents and parents lived in Italy.