By Raeleen Mautner

Italy’s emphasis on the importance of eating well goes at least as far back as Renaissance times, when Leonardo da Vinci wrote in his Notebooks: “In order to stay in optimal health, eat only when you want and relish food; chew thoroughly that it may do you good; have it well-cooked, unspiced and undisguised; and let your food—rather than medicine—be your source of wellness.”

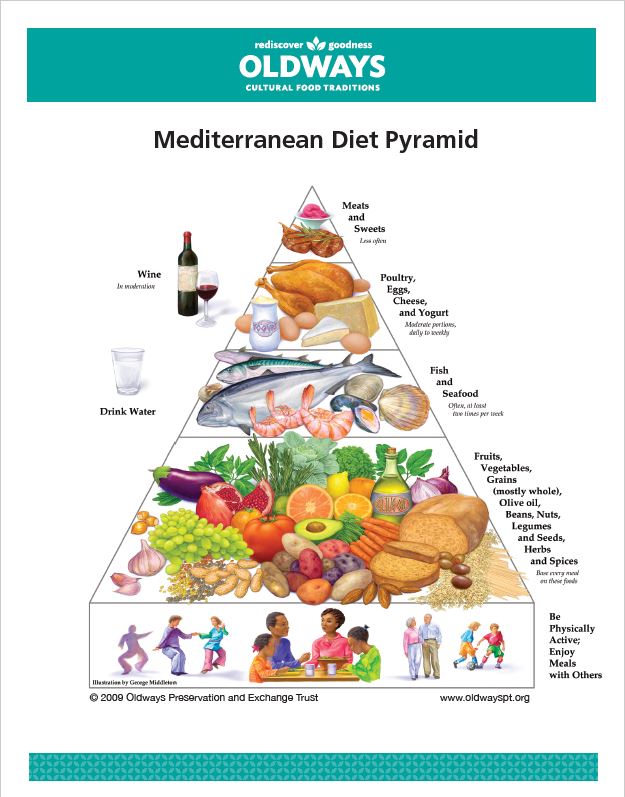

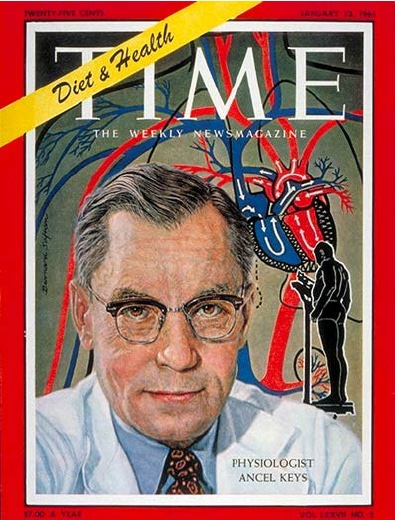

The Mediterranean Diet (MD) was originally associated with Ancel Keys, who was a physiologist at the University of Minnesota, and his biologist wife Margaret Haney. In 1951 Keys gave a lecture at the first FAO Congress (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations) after WWII. Only one attendee, a doctor named Gino Bergami from the University Hospital of Naples commented on Keys’ observation of the high incidences of cardiac death in the U.S., among men ages 30-59. Bergami told Keys that cardiovascular disease was extremely uncommon in his hospital, and later invited Keys to come to check for himself. Keys and his wife didn’t hesitate. Haney immediately began collecting and analyzing blood samples of Neapolitan steelworkers, comparing them with the samples of men in Minnesota. There was a significant difference in cholesterol levels, which could partially explain the difference in heart attack rates. But Keys and Haney became fascinated with a broader definition of the Mediterranean diet, which went beyond eating style to a more holistic lifestyle cultural pattern, that promoted both physical and emotional wellbeing. Beyond the alimentary emphasis on fresh fruits and vegetables, whole grains, legumes, nuts; moderate to sparing use of olive oil, dairy, wine, and limited inclusion of meats and sweets; also came a practice of eating together with family and friends, daily walking or bicycling, and coming together in community venues like parish churches for group prayer.

While research on Mediterranean dietary patterns has consistently demonstrated its preventative effect on cardiovascular disease, type-2 diabetes, high blood pressure, inflammation, and high cholesterol; a more recent study has found that adherence to a Mediterranean diet, due to its high nutrient and antioxidant content, as well as its anti-inflammatory properties, may also help to counter the predisposing conditions that make one more likely to get COVID-19 infections. Additionally, it may attenuate the severity of infections in those who do contract it. One known risk that makes us more vulnerable to the virus is obesity.

Observational data alone would suggest that the Pandemic has wreaked havoc with our eating practices, worldwide. Most everyone I talk to complains of having gained weight during the lockdown. A recent survey study focused on data collected from a large online survey of eating practices across the United States. The study examined the effect of pandemic-induced stress on eating patterns. While some respondents reported an improvement in their eating behaviors, nearly a third said their diet had worsened during the COVID-19 pandemic; a virus that resulted in high mortality rates, lockdowns, shutdowns of businesses, nation-wide layoffs, and disruption in people’s social life and interactions.

Challenges to deriving the protective benefits associated with a Mediterranean way of eating include misconceptions about this alimentary style (hint: it is not about eating mounds of spaghetti topped with bocce-ball-sized meatballs and swimming in a sea of olive oil), or consistency in adhering to this healthful eating style. It is also important to acknowledge that new research shows that a low-fat vegan diet (i.e., eliminating all animal products and added fats), when compared to a traditional Mediterranean diet resulted in greater reduction of body weight, fat mass and visceral fat, as well as increased insulin sensitivity and improved blood lipids in a large, randomized cross-over trial. While most Italians (and Italian Americans), however, would probably refuse to give up their cheese, fish, or add olive oil to their dishes, any step we take along a spectrum towards eating fewer animal products and more greens and legumes, is a step in a healthier direction.

Ancel Keys, by the way, lived to be 100, and his wife reached the age of 97. In 2010 UNESCO recognized the Mediterranean Diet as an Intangible Heritage of Humanity; and in 2012 it was included as one of the most sustainable diets on the planet by the FAO.

References:

A.M. Angelidi, A. Kokkinos, E. Katechaki et.al. (2021) Mediterranean diet as a nutritional approach for COVID-19. Metabolism Clinical and Experimental 114.

Neal D. Barnard, Jihad Alwarith, Emilie Rembert, Liz Brandon, Minh Nguyen, Andrea Goergen, Taylor Horne, Gabriel F. do Nascimento, Kundanika Lakkadi, Andrea Tura, Richard Holubkov & Hana Kahleova (2021): A Mediterranean Diet and Low-Fat Vegan Diet to Improve Body Weight and Cardiometabolic Risk Factors: A Randomized, Cross-over Trial. Journal of the American College of Nutrition. DOI:10.1080/07315724.2020.1869625

Khubchandani, J., Kandiah, J., & Saiki,D. (2020). The COVID-19 Pandemic, Stress, and Eating Practices in the United States. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology, and Education, 10 (950-956).

Martini, D. (2019). Health Benefits of Mediterranean Diet. Nutrients, 11, 1802; doi:10.3390/nu11081902

Moro, E. (2016). The Mediterranean Diet from Ancel Keys to the UNESCO Cultural Heritage. A Pattern of Sustainable Development between Myth and Reality. Social and Behavioral Sciences 223, 655-661.