A Review by LindaAnn Loschiavo

“This is the slum that faces the bay on the seaward side of the Brooklyn Bridge,” Arthur Miller’s narrator, the lawyer Alfieri (Michael Gould) informs the audience. “This is the gullet of New York swallowing the tonnage of the world.”

In other words, this bleak perspective ironically contradicts every rosy New York City real estate ad you’ve ever seen espousing the charms of “6 Rms Riv Vu.” The vista in Miller’s 1955 drama is of rough-and-tumble Red Hook, populated by dock workers, laborers, and hustlers. It will be the temporary home of two Sicilian immigrants, men who entered the United States illegally by boat, seeking employment and better wages than their homeland could offer. Thirty-two-year-old Marco (Michael Zegen), dark of hair and demeanor, is married with three youngsters — — the oldest “sick in his chest” — — and eager to send money home. In contrast, his brother Rodolfo (Russell Tovey), a light-hearted blond bachelor, loves to sing and have fun. “When you have no wife,” Marco says of him, “you have dreams.”

In other words, this bleak perspective ironically contradicts every rosy New York City real estate ad you’ve ever seen espousing the charms of “6 Rms Riv Vu.” The vista in Miller’s 1955 drama is of rough-and-tumble Red Hook, populated by dock workers, laborers, and hustlers. It will be the temporary home of two Sicilian immigrants, men who entered the United States illegally by boat, seeking employment and better wages than their homeland could offer. Thirty-two-year-old Marco (Michael Zegen), dark of hair and demeanor, is married with three youngsters — — the oldest “sick in his chest” — — and eager to send money home. In contrast, his brother Rodolfo (Russell Tovey), a light-hearted blond bachelor, loves to sing and have fun. “When you have no wife,” Marco says of him, “you have dreams.”

A reference to dreams calls to mind Puccini’s Rodolfo, the poet and dreamer of “La Boheme,” who sings this to Mimi: In poverta mia lieta/ scialo da gran signore/ rimi ed inni d’amore,/ Per sogni e per chimere/ e per castelli in aria/ l’anima ho milionaria. Bohemian Rodolfo and his Brooklyn namesake have put their faith in dreams of love and castles in the air. This trait causes an uneasy feeling in serious men such as Marco and Eddie Carbone, especially when Eddie’s orphaned niece Catherine (Phoebe Fox) smartens up her appearance for the newcomers by donning black pumps.

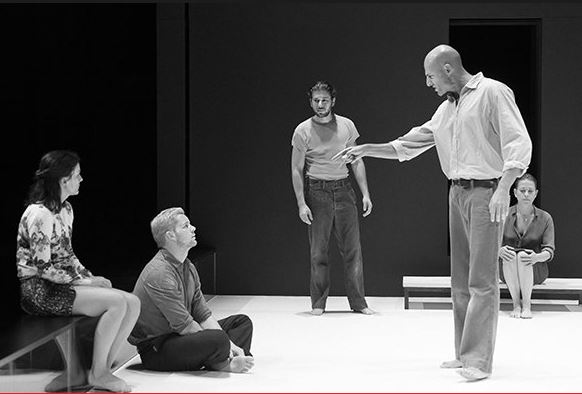

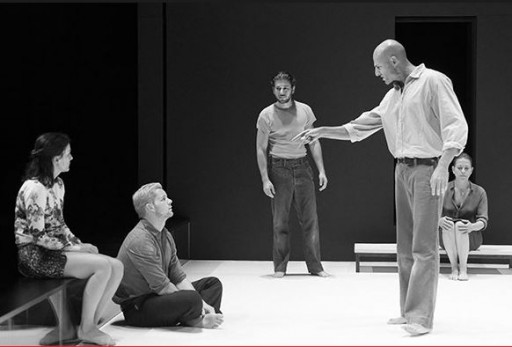

“What’s the high heels for, Garbo?” asks Eddie. Angry, embarrassed, Catherine retreats to the bedroom to change. And this is one of many incidents director Ivo Van Hove seizes upon to ratchet up the tension. Since the entire cast is barefoot, Catherine’s brief strut in stilettos is even more striking. Earlier in Act I, Eddie notices his niece’s short skirt and comments: “I don’t like the looks they’re givin’ you. The heads are turnin’ like windmills.” In other words, showing off has consequences. Rodolfo also reveals he enjoys sunning himself in the spotlight. He performs a song about a lover jilted by his girlfriend, “Paper Doll,” impressing Catherine but drawing a rebuke from Eddie, who disguises his jealousy as a precaution. “Look, kid; you don’t want to be picked up, do ya? Because we never had no singers here. . . and all of a sudden there’s a singer in the house, y’know what I mean?”

It’s obvious that Eddie Carbone (whose surname means coal or carbon in Italian) hears the music of misrule disrupting his domain. His niece was just hired by a plumbing company, a job that will bring her a salary and freedom from his control. Now his buoyant blond boarder is talking about buying a motorcycle and “thousand-lire notes” tourists threw after he performed a suite of Italian arias in a hotel. A new world order is emerging, a universe where young women go to business and youthful immigrants supplant older Americans in the workplace.

Eddie is a stubborn, old school type of guy, a real “capa tosta,” but he’s denied our sympathy because his incestuous fixation on his teenage niece has violated the natural order of things. When Beatrice (Nicola Walker) presses, “When am I gonna be a wife again, Eddie?,” he claims he doesn’t feel well. “It’s almost three months you don’t feel good, Eddie,” his skeptical spouse reminds him. Even before it’s clear to the audience that Eddie’s been avoiding conjugal relations, it is obvious he’s paying improper attention to Catherine, thereby establishing the unsavory dynamics that will spiral out of control and lead to violence.

As Arthur Miller said: “My way of writing plays involves the birds coming home to roost. It’s also the Greek way, and Ibsen’s way. It’s about challenges that were not met when they came up and so those challenges return and haunt people. History is of the essence in that form.”

When I discovered that the Olivier Award-winning Young Vic Production of this play would be opening in November on Broadway at the Lyceum Theater, I read every article I could find. Rebecca Mead’s feature for The New Yorker was the most startling. She writes: “When David Lan, the Artistic Director of the Young Vic, first suggested to [Ivo] van Hove that he might direct ‘A View from the Bridge,’ he resisted. As Versweyveld recalls it, van Hove said, ‘It’s a well-made play. I hate it. There is little room for any roller-coaster ride.’” Despite his initial resistance, van Hove helmed a gripping two hour tragedy of the common man that was masterfully cast. Though Eddie Carbone is described as “a husky, slightly overweight longshoreman,” tall, sleek, taut Mark Strong brought him to life along with the simmering sexual ragù smoking between him and Phoebe Fox as Catherine.

The Belgian director eliminated the props and pared down the players (from sixteen to seven) and the set. Miller’s cluttered 1950s Brooklyn living room became a stark white box that weeps at the beginning of Act I with a faux-baptism of overhead water, as the laborers wash up, and concludes with a rage-filled red rain soaking all the players. Scenic and lighting designer Jan Verswyveld recreated the same intimate setting that the production generated in London’s West End, mimicking an ancient Greek theater set.

As if Arthur Miller’s stern morality play wasn’t intense enough, the tension was also heightened by Tom Gibbons, the sound designer who introduced “Drumming,” a minimalist piece by composer Steve Reich in between dialogues.

In every way possible, the production unmoors itself from the McCarthy Era. The costumes by An D’Huys are neutral and almost institutionally drab except for Catherine’s tacky flowered top and mismatched mini skirt. And despite an occasional nod to the local patois (“So what kinda work did yiz do?”), for the most part the actors’ speech patterns are far from Gowanus. Be prepared for the array of non-Brooklyn accents and the unreality of Sicilian laborers who hop off the boat and converse in perfect English.

In his introduction, the playwright noted how a London production’s “new conditions created new solutions.” Miller explained, “The British actors could not reproduce the Brooklyn argot and had to create one that was never heard on heaven or earth. Already naturalism was evaporated by this much: the characters were slightly strange beings in a world of their own.” Given the opportunity to watch the play from a limited number of on-stage seats, I encourage everyone to see it from such a privileged perch. I often felt more like a voyeur, looking into a neighbor’s apartment, than a theatre-goer. It was an intimate and thoroughly unforgettable theatrical experience. Bravissimo. “A View from the Bridge” runs through February 21, 2016 at the Lyceum Theater, 149 West 45th Street, NYC. Link: http://lct.org.