Interview by Tiziano Thomas Dossena

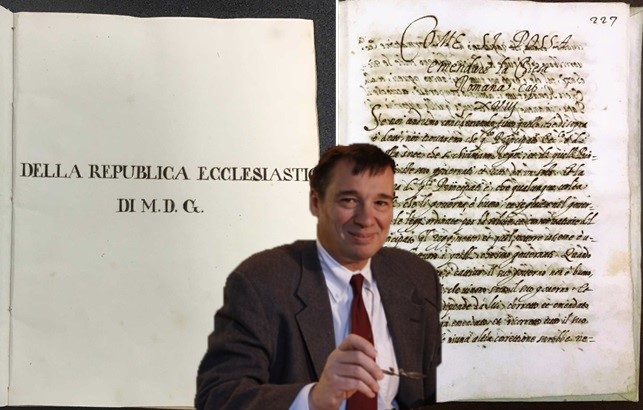

William Connell is a historian who holds the La Motta Endowed Chair in Italian Studies at Seton Hall University. He has devoted much of his career to the historical study of Italy and Italian Americans. Recently he was awarded a prestigious Andrew Carnegie Fellowship. In June 2023 the comprehensive Routledge History of Italian Americans, which he co-edited with Stanislao Pugliese, won the 75th Anniversary Prize of the Italy-USA Fulbright Commission.

Connell received his BA from Yale University and his PhD from the University of California at Berkeley. He taught at Reed College and Rutgers University before coming to Seton Hall, where he was Founding Director of Seton Hall’s Alberto Italian Studies Institute, which has become New Jersey’s pre-eminent center for the study of Italian culture. He has been a Harvard/I Tatti Fellow and a Member of the Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton. For 25 years he was Secretary of the Journal of the History of Ideas. His books and articles have been published in Italian, French, Spanish, Russian, Romanian and Farsi. He frequently lectures on Italian history at the universities of Turin, Milan, Pisa, Florence, Rome, Naples, and Bari.

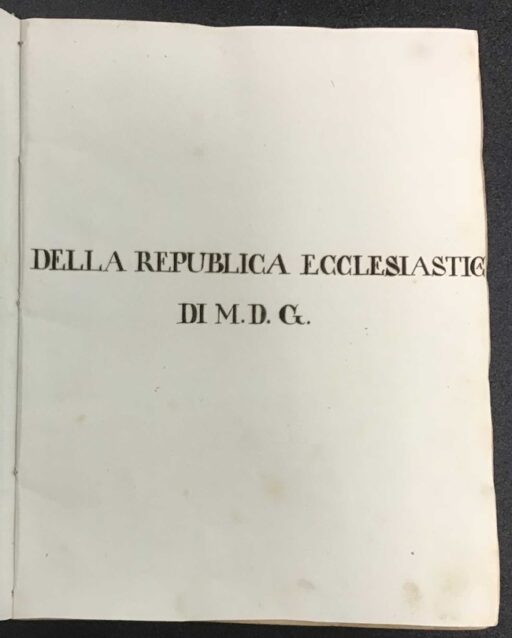

Last May, Dr. Connell published with the Italian editor Einaudi the book “Della Republica Ecclesiastica” [On the Ecclesiastical Republic], but Donato Giannotti, a book that everyone thought was never to be found, though there had been a few historical references to it, such as the one from Gian Vincenzo Pinelli. I previously interviewed Dr. Connell, 10 years ago, in April of 2013, when he had just published his translation of “The Prince” by Niccolò Macchiavelli. We were able to obtain another interview with him relating to this fantastic discovery.

L’Idea Magazine: Einaudi published “Della Republica Ecclesiastica” di Donato Giannotti, which you edited. Could you tell our readers why Donato Giannotti’s book, “Della Republica Ecclesiastica,” is so important?

William Connell: It’s quite remarkable, but, believe it or not, this is the first history of the Church ever to have been written by a learned layperson. All of the previous histories—and there weren’t all that many—were written by clergy or monks. This book, written in 1541, begins with St. Peter and ends with the papacy of Paul III, was able to draw on the many ancient and medieval sources recovered during the revival of learning in the Renaissance, and the author was able to study and compare them with a critical eye. It’s a history that focuses on Church governance, and it aims to correct the growing corruption the author perceived in ecclesiastical administration. So, it’s not a history of saints and miracles, but instead, it treats the growth of papal power and its abuses. Although he wrote at the time of the Protestant Reformation, the author was staunchly on the Catholic side. Yet his suggestion for reforming the Church was radical: he proposed that bishops be elected by the clergy and laity of each diocese, that the papal monarchy be abolished, and that the Church be ruled by a senate of virtuous cardinals who would make their decisions by majority vote after open debate. That such a book was never published and remained in manuscript out of circulation for almost 500 years is not surprising. During the 16th century, the papacy was instead strengthened, and the year after this history was written the Roman Inquisition was established to investigate and prosecute, among other subjects, challenges to papal primacy.

William Connell: It’s quite remarkable, but, believe it or not, this is the first history of the Church ever to have been written by a learned layperson. All of the previous histories—and there weren’t all that many—were written by clergy or monks. This book, written in 1541, begins with St. Peter and ends with the papacy of Paul III, was able to draw on the many ancient and medieval sources recovered during the revival of learning in the Renaissance, and the author was able to study and compare them with a critical eye. It’s a history that focuses on Church governance, and it aims to correct the growing corruption the author perceived in ecclesiastical administration. So, it’s not a history of saints and miracles, but instead, it treats the growth of papal power and its abuses. Although he wrote at the time of the Protestant Reformation, the author was staunchly on the Catholic side. Yet his suggestion for reforming the Church was radical: he proposed that bishops be elected by the clergy and laity of each diocese, that the papal monarchy be abolished, and that the Church be ruled by a senate of virtuous cardinals who would make their decisions by majority vote after open debate. That such a book was never published and remained in manuscript out of circulation for almost 500 years is not surprising. During the 16th century, the papacy was instead strengthened, and the year after this history was written the Roman Inquisition was established to investigate and prosecute, among other subjects, challenges to papal primacy.

L’Idea Magazine: Where and how did you find the original manuscript?

William Connell: It was a fun adventure, really. In June of 2018, I was invited to present the large history of Italian Americans I had co-directed at the annual literary festival in Salerno. I had never been to Salerno, and when I arrived, I discovered there was a ferry up the coast to Amalfi, which I had always wanted to visit. So, I toured Amalfi’s Duomo, hiked above the town, and found a trattoria where they served a delightful Fiano di Avellino. When I returned to the ferry dock, there was a substantial wait, so, to pass the time, I wandered into one of those antique shops of a kind known to most travelers—the sort of store that sells nice, small things that tourists can fit in their suitcases: pottery, prints, watercolors, figurines, paperweights. Toward the back, on a side shelf, I noticed a row of old books. Looking them over, I discovered four that were bound manuscripts rather than printed volumes. Two were from the sixteenth century! Little time remained if I was to catch the ferry, so I found the owner and asked the price for the four books. He said he would sell them to me for 500 euros each, and since I know something of the trade, I considered this a bargain, so although there was no time to read them, I bought them for the library at Seton Hall University, where I teach.

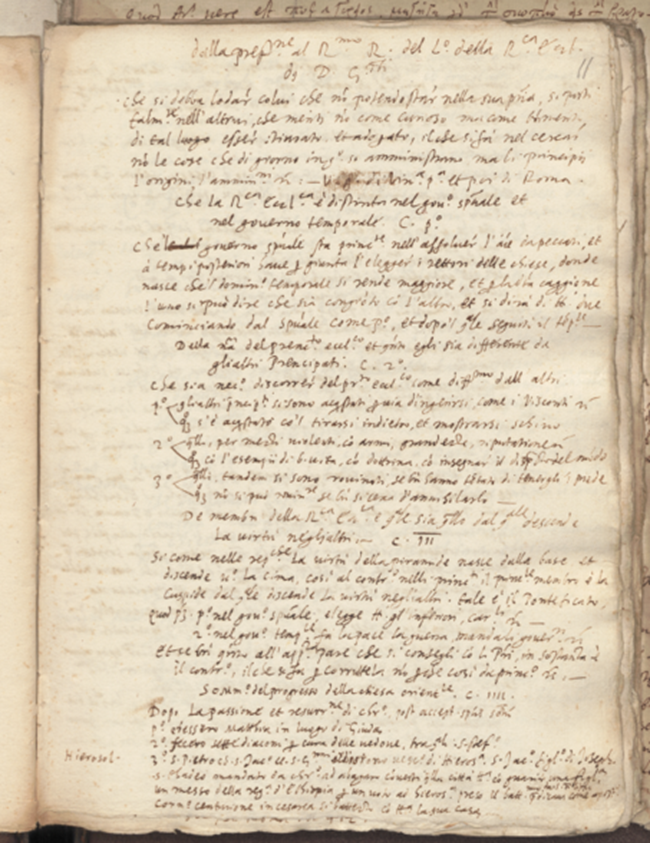

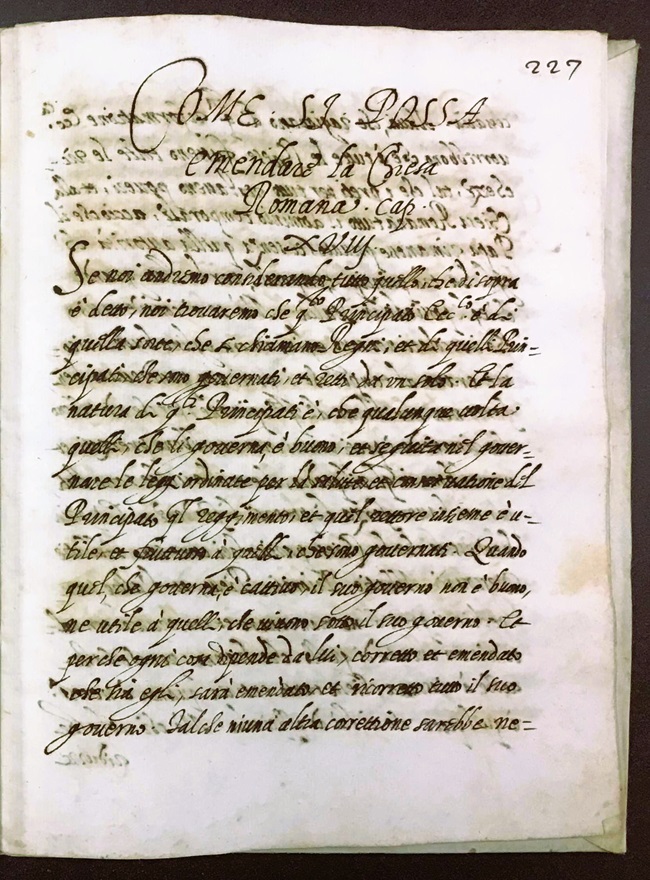

Each of the four manuscripts was interesting in its own way, but the one that stood out had a title page that read: “DELLA REPUBLICA ECCLESIASTICA DI M.D.G.”. The text was long–233 folio pages, recto and verso—written in a neat sixteenth-century hand in the Italian language. The fact that the author was identified only with the initials “M.D.G.” suggested an attempt to mask his name. But what was most striking was the final chapter, titled “Come si possa emendare la Chiesa Romana” [How the Roman Church might be reformed], that proposed stripping the pope of all his powers and passing them to the College of Cardinals!

L’Idea Magazine: Since it was signed only with the initials MDG, what made you suspect it was the missing manuscript by Giannotti?

L’Idea Magazine: Since it was signed only with the initials MDG, what made you suspect it was the missing manuscript by Giannotti?

William Connell: In the late fifteenth and sixteenth century there were a number of important political theorists who made a sharp distinction between governments that were monarchies (and ruled by one person) and republics (ruled by magistracies consisting of citizens). The republicans saw that monarchs often became tyrannical, and they saw wisdom in rule by consensus through deliberative bodies. Donato Giannotti was a leading republican, still today well-known to scholars on account of books he wrote about the republics of Florence and Venice. The idea that the Church could be turned into a republic was indeed surprising, but the idea must necessarily have come from a republican. The initials MDG stood for “Messer Donato Giannotti”. “Messer” [My Lord] was an honorific title for people who had doctorates, and early in his career, Giannotti had been a professor at the University of Pisa.

Portrait in the Corridoio Vasariano (painted after 1658)

William Connell: It turned out to be easier than expected. By happy coincidence, when I began studying at Berkeley for my PhD in the 1980s, one of my professors, Randolph Starn, had published 10 years before then a book of letters that this same Donato Giannotti had written in Latin. Since I happened to own a copy of that book of letters it took only a few minutes to follow up on my hunch. In one of these letters, dated 1541, Giannotti stated that he “expected soon to finish his book On the Ecclesiastical Republic”. Randy Starn, who still lives in Berkeley, remains a good friend, and I correspond with him often.

In this case, so as to surprise him, I remained silent about the discovery. Only when the book was in proofs with the publisher did I let him know about it. Needless to say, he’s been pleased.

L’Idea Magazine: Who was Donato Giannotti and why did he define himself as a “foreigner in the Church?”

William Connell: Giannotti had a long career, most of it in exile from his native Florence. In the 1520s he left his professorial position and began to be involved in Florentine politics. In 1527, he became a chancellor of what would prove to be the last republican government in Florence, which ended in 1530 when rule passed to the dynasty of Medici princes. Giannotti was first imprisoned and then went into opposition as an exile, finding a home in Rome and the patronage of a Florentine Cardinal, Niccolò Ridolfi, who like him was a republican opponent of the Medici. As an exile from Florence, Giannotti was a “foreigner” in Rome. But he was also a kind of ‘stranger’ as someone employed by the Church, even though he was on the best of terms with Cardinal Ridolfi. Giannotti was proud of his lay identity, and he made it clear to friends that he did not want to become one of the clergy. After Ridolfi died he went into the service of a French Cardinal, but again he remained a layman. Only at the very end of his life, when Pius V asked him to become a papal secretary, did he relent and don the robes of a clergyman, something a close friend said he thought would be “impossible”. I think the best way to explain this is to say Giannotti thought the Church was essential to the ordering of European society. He wanted it to be strong and a force for the good. Yet personally he cared little for theological questions, and he wanted to preserve a measure of critical distance from the Church.

William Connell: Giannotti had a long career, most of it in exile from his native Florence. In the 1520s he left his professorial position and began to be involved in Florentine politics. In 1527, he became a chancellor of what would prove to be the last republican government in Florence, which ended in 1530 when rule passed to the dynasty of Medici princes. Giannotti was first imprisoned and then went into opposition as an exile, finding a home in Rome and the patronage of a Florentine Cardinal, Niccolò Ridolfi, who like him was a republican opponent of the Medici. As an exile from Florence, Giannotti was a “foreigner” in Rome. But he was also a kind of ‘stranger’ as someone employed by the Church, even though he was on the best of terms with Cardinal Ridolfi. Giannotti was proud of his lay identity, and he made it clear to friends that he did not want to become one of the clergy. After Ridolfi died he went into the service of a French Cardinal, but again he remained a layman. Only at the very end of his life, when Pius V asked him to become a papal secretary, did he relent and don the robes of a clergyman, something a close friend said he thought would be “impossible”. I think the best way to explain this is to say Giannotti thought the Church was essential to the ordering of European society. He wanted it to be strong and a force for the good. Yet personally he cared little for theological questions, and he wanted to preserve a measure of critical distance from the Church.

L’Idea Magazine: How would you place Giannotti in reference to the contemporary reform movements?

William Connell: To begin with he was anti-Protestant. He opposed Martin Luther. He thought disputes among theologians about doctrinal issues resulted in unnecessary chaos that enabled tyrannical monarchs, like the Habsburg Emperor Charles V, to enlarge their realms, while weakening Europe in confronting the ongoing invasions of the Islamic Ottoman Empire. There were Catholics within the Church who thought that to reform abuses within the Church what was needed was a spiritual reformation focused on the imitation of Christ that would bring for the blossoming of a truer and deeper Christian faith. This, too, seems not to have made an impression on him. Giannotti approached the Church with something of the manner of a modern-day management consultant. His goal was to change the constitutional form of the Church in such a way that it would not suffer tyranny at the hands of its own leaders, which is to say the popes, and so that it would be organized effectively and justly, with the approval of its subjects, which is to say all Christians, and thus remain fiercely independent and avoid falling under the political control of external tyrants. He saw the political goal of independence as far more important than the doctrinal and spiritual issues that were motivating other reformers.

L’Idea Magazine: Why is it that Giannotti’s account represents something new for his times in reference to the history of the Church?

William Connell: No one, to my knowledge, had offered in writing a program of constitutional reform that would have ended the papal monarchy. This republican vision was absolutely new. And it was so radical that it had to be “kept under wraps”. Thus, the book never circulated beyond a few friends and was never published. But it was also new in that it was a study of the Church from a purely institutional angle. As I said earlier, this is a history of the Church that does not discuss saints, missionaries, miracles or devotional practices. Nor does it focus on the personalities of the different popes, as some previous writers had done. It is instead a history of how the Church was administered, how its power grew, and how it interacted with secular powers while acquiring its own set of prerogatives in the secular world.

L’Idea Magazine: What were the sources used by Giannotti in the writing of his book?

William Connell: Giannotti was fortunate in that Renaissance humanists of the 15th century had collected relevant ancient and medieval texts from cathedral libraries and monasteries throughout Europe, and from the Eastern Roman Empire that was falling under the control of the Ottoman Turks. Moreover, with the invention of the printing press, these accounts became easily available. One of the most valuable sources was a huge collection of Church documents, published in approximately 3000 pages, that was made by a Flemish Franciscan friar, Pierre Crabbe. No one previously had thought to write a careful history from these sources.

L’Idea Magazine: What were the views of Giannotti on republics versus principates?

William Connell: As mentioned earlier, Giannotti, like some other contemporary republicans, thought that monarchies (or “principates”) gave too much power to a single person, so that society and its government could easily fall under the sway of a tyrant. Hereditary rule meant that a ruler of uncertain quality might ascend the throne. But even election (as with the papacy) could result in a ruler who proved tyrannical once in place. Giannotti uses the metaphor of a pyramid to describe the two types of government. In a monarchy, the particular character of the regime descends from the apex and is dependent on a single person, for good or for ill. In a republic, the particular virtue of the regime ascends from the people, who give it a firm foundation and restrain any improper impulses of those at the summit.

L’Idea Magazine: What was the role of Giannotti in the failed candidacy of Cardinal Ridolfi at the Conclave of 1549-1550?

William Connell: So, this book was written at the request of Giannotti’s patron, Cardinal Ridolfi. Giannotti ends the book by saying that his reform could only be achieved under a newly elected pope who was exceptionally virtuous and well-intentioned. This pope would have to be ready to use the extensive monarchical powers of the papacy to put in place, essentially “to found” a republic, and he would then have to surrender his monarchical powers to that republic. The man he says he thinks can do this is none other than Cardinal Ridolfi. The extent to which either man truly believed this was possible is not clear. But at the next Conclave, after the death of Paul III, in 1549-50, Cardinal Ridolfi was nearly elected pope. When the candidacy of the preliminary favorite, Reginald Pole of England, collapsed after several months, Ridolfi looked to be the one who would be elected.

And Giannotti was there with him in the Sistine Chapel as his “conclavist”—the campaign manager or lobbyist who was there to lobby the other cardinals and to keep a running tally of votes for or against. But with Ridolfi on the verge of being voted in as pope, the man fell unexpectedly ill. He had to leave the Conclave and a few days later, after a day in which he had been expected to return, there was a relapse and he suddenly expired. Immediately poisoning was expected. The remaining cardinals were put on ‘poison alert’, and they soon after elected Cardinal Del Monte as Julius III. And meanwhile, an autopsy was performed on Ridolfi by an illustrious surgeon, who declared that Ridolfi had indeed died from poison. So here we have one of history’s what-ifs… If Ridolfi had lived and been elected pope, would he have instituted a reform that would have had bishops elected locally, ended the papal monarchy, and transferred all power to the College of Cardinals…?

L’Idea Magazine: Do you believe the changes proposed by Giannotti could have been realized or were they too idealistic?

William Connell: To be honest, I think they were too idealistic. Too idealistic for the 16th century and too idealistic to be realized even today. But they pointed toward a more democratic direction in Church governance that, long after, at the Second Vatican Council, the Roman Church would indeed begin to experiment with, as it continues to do today.

L’Idea Magazine: Do you think there will be a translation of this book in the near future?

William Connell: It’s been important to publish the original Italian text, so that scholars and theologians can study with care the precise wording, the author’s ideas, and the context in which it was written. That was the goal of this first edition with Einaudi, an illustrious Italian publishing house. I must say that they did an excellent job in producing it. A translation into English will follow soon, but first, though, the original Italian version–of a text that has been completely unknown until now–needs to circulate in the most authoritative fashion possible.

L’Idea Magazine: We thank you for your time and your explanations. Do you have a message for our readers?

William Connell: Above all a word of thanks to L’Idea and its splendid editorial director, Tiziano Dossena. Our discussions have always been ones from which I take away from him as he could ever take away from me.