By Laura (DiLiberto) Klinkon

Objective as an adjective can be confusing for those who understand poetry primarily as expressing emotions, and yet, with the adoption of free verse as the “modern” way to write poetry, some poets have felt the need to highlight devices other than traditional rhyme and meter as ways to explain the new forms. One group of these mid-twentieth century poets became known as Objectivists.

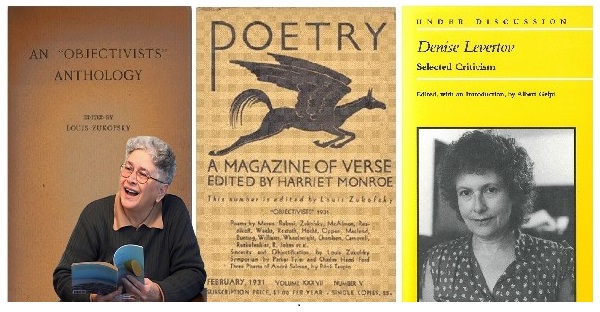

Having more familiarity with traditional forms, I have chosen to explore the Objectivist theory of poetry, in part to better understand modern free verse poetry. My main source is Denise Levertov,* who closely associated herself over her lifetime with the Objectivist poet William Carlos Williams and, indirectly through him, with Louis Zukofsky. In the present article, my quotations from Levertov’s essays are simplified to bring out her main premises. Please also note that the theories presented have no affinity with Ayn Rand’s philosophy of Objectivism.

Free verse poetry that does not have end-rhyme or regular meter has its official American origin in Imagism, a movement that began in about 1913 by Ezra Pound. To these important developments, Imagism added the requirements of clarity and condensed language. Objectivism, which grew from Imagism, supported these requirements but added others, especially ideas regarding the “thing,” a redefinition of the poetic “foot,” and a re-explication of the “line.” As for its ideas on content and pathos, it legitimized history as content but rejected mythology, and emphasized musicality as a vehicle for emotions that was dependent on the poem’s inner and outer “voices.”

The main originators of Objectivism are Louis Zukofsky, who as a 27-year-old, guest-edited the 1931 Objectivist issue of the Chicago-based magazine Poetry, William Carlos Williams a doctor and highly engaged poet who in 1928 had befriended Zukofsky though the latter was 21 years his junior, and Denise Levertov, a poet who arrived from England in the late ’40s as a 24-year-old and remained a long-time protégée of Williams. Though in addition to Zukofsky and Williams, other poets appeared in the original Objectivist issue of Poetry and in the 1932 Objectivist Anthology, these two poets, with Levertov, who I am mainly citing, form a core group of theorists.

One persuasive Levertov concept is that moderns do not think in absolute terms, so that the modern free-verse poem, as a mirror of the poet’s thought process, is not likely to reflect conclusive “answers” as was typical in traditional poems; truth today being more relative, modern poetry is inevitably written without pat conclusions, as may occur, for example, in the final couplet of a sonnet.

Yet, the Objectivists, despite modern relativity and the “freedom” implied in “free verse,” expressed a serious insistence on form, craft, and technique. Zukofsky, as its earliest proponent, emphasized that modern poets should be “sincere” craftsmen in their art, should pursue clarity through precise use of common language, and should “sing” about the real world.

Williams, who is said to have perfected his craft after life-long exploration, stated as his most important but apparently misunderstood theory: “There are no ideas but in things.” which seems to address the “objective” in Objectivism. With the word “thing” he was referring to the concrete object, yet “objectivity” by another Objectivist poet, George Oppen, was understood as an attitude toward the “thing,” that is, toward the poem itself or the object of interest in the poem. Thus, there were from the start, differences of opinion among the Objectivist poets. Levertov, meanwhile, elaborates on the way Williams’ idea should, in her mind, be understood.

She begins her essay, “The Ideas in the Things,” with the statement, “There are many more ‘ideas’ in William Carlos Williams’ ‘things’ than he is commonly credited with.” She then explains that “… for much of his life Williams [favored the] objective [as a way to]…free poetry…of…sentimental intellectualism which…scorns the literal [object] …” If one misinterprets the importance of ideas in Williams’ “thing,” he or she “denies the equipoise [or the balance between] … the thing and idea… [and dismisses the] … concrete image as the very incarnation of thought.” She adds: “Readers who come to Williams … with the expectation of … a … single-visioned objectivity … [tend to] miss the resonances … or sense of discovering … an unnamed but intensely intuited whole ….”

To a significant degree, Levertov minimizes the very “concreteness” that Williams is popularly known for. In her essay, “Some Notes on Organic Form,” Levertov suggests how her application of Gerard Manley Hopkins’ “inscape” concept can help a reader to understand the dynamics of objective free verse poetry; readers should be looking for “the pattern of essential characteristics both in single objects and … in objects that … relate to each other … [including] intellectual and emotional experience [in the form of] … analogies, resemblances, [or] natural allegories ….”

With statements such as these, Levertov seems to lift us out of the realm of concreteness into the realm of simile, metaphor, and allegory that we typically identify with traditional poetry—devices readers of poetry generally understand. The way “things” appear together in a poem to elicit a “feeling” about the poem rather than a mere intellectual understanding, according to Levertov, depends on our intuitive grasp.

And it appears that musicality may assist intuition; Levertov and Williams, as well as Zukofsky, emphasize musicality as a tool for the careful crafting of the poem and its emotional reception by the reader. Williams, in particular, is known for two key devices relevant to musicality: the “variable foot” and the “triadic line,” which as Levertov points out, he spent much of his life perfecting—the triadic line consisting of three parts of equal duration.

Her essay entitled “On Williams’ Triadic Line, or How to Dance on Variable Feet,” explains the “variable foot,” by emphasizing its duration as the important aspect, rather than the syllable or stress count typical of the traditional poetic “foot.” She also explains that a polysyllabic foot will be read faster than one with fewer syllables so as to result in three triadic feet of equal duration. This part of Williams’ theory causes some skepticism because determining where one foot ends and the next begins has to be determined by the subjective understanding of the individual reader. Levertov solves this problem to some degree, by saying that the natural stress in the words used indicate the intended pace and emotional tone of the triad.

With regard to musicality in any free verse line, Levertov’s essay “On the Function of the Line,” emphasizes the efficacy of line breaks, indentations, punctuation, and stanza spaces that, she says, function like notes on a musical score—the value of the break at the end of a line, she adds, signifies approximately half the duration of a comma. In Williams’ triadic line, the musical pace of the poem is typically established by its first variable foot.

In the same essay, Levertov points to an inner voice of the poem that follows the thinking process or the singing voice of the poet. There may be, moreover, an outer voice—heard when the poem is read aloud, potentially producing a musical counterpoint similar to the counterpoint in musical performances.

Levertov does complain that readers of poetry can, in encountering Objectivist free verse poetry, miss its nuances. They may consider that “free verse” allows uncalculated freedom, that “things” may be nothing more than poetic starting points, that the “things” referred to simply make good images, while breaks and spaces are mere substitutes for commas, etc. But Objective poetry as Levertov, Williams, and Zukofsky explain it has more depth than immediately accounted for, depending as it does on the poet’s inner voice and the reader’s intuitive grasp, both of which are based on “sincere” attention, as all of these originators have attested.

* Levertov, Denise. New & Selected Essays, New Directions Publishing Corp,, New York, NY, 1965-1992

A related video presentation by the author was shown at the UNESCO World Day of Philosophy in Rochester, New York, on Nov. 18, 2021.