Interview by Tiziano Thomas Dossena

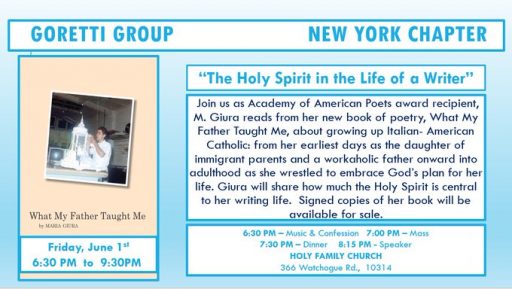

Maria Giura PhD is the author of Celibate: A Memoir (Apprentice House), which won a 2020 Independent Press Award, and What My Father Taught Me (Bordighera Press), which was a finalist for the Paterson Poetry Book Prize. Her writing has appeared in several journals including Prime Number, Presence, Italian Americana, Lips, VIA, Ovunque Siamo, Brooklyn Film & Arts Festival and Tiferet. She has won awards from the Academy of American Poets and the Center for Women Writers and was selected to judge the Lauria/ Frasca Poetry Award. She has taught Literature and Writing at St. John’s University, Montclair State University, and Binghamton University where she earned her doctorate in English. She lives in NYC.

Maria Giura PhD is the author of Celibate: A Memoir (Apprentice House), which won a 2020 Independent Press Award, and What My Father Taught Me (Bordighera Press), which was a finalist for the Paterson Poetry Book Prize. Her writing has appeared in several journals including Prime Number, Presence, Italian Americana, Lips, VIA, Ovunque Siamo, Brooklyn Film & Arts Festival and Tiferet. She has won awards from the Academy of American Poets and the Center for Women Writers and was selected to judge the Lauria/ Frasca Poetry Award. She has taught Literature and Writing at St. John’s University, Montclair State University, and Binghamton University where she earned her doctorate in English. She lives in NYC.

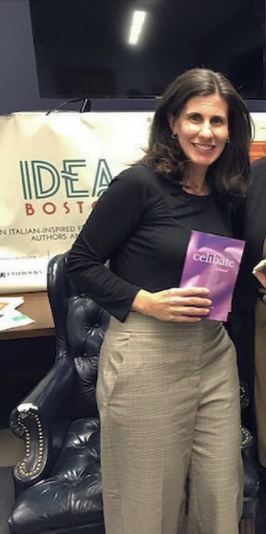

L’Idea Magazine: Your book “What My Father Taught Me,” a collection of memory poems, was a finalist for the Paterson Book Prize. Are these poems all about your experience at home?

Maria Giura: The first half of the book includes poems about the home I grew up in Dyker Heights, Brooklyn, and the second half includes poems about searching to feel at home in the world. Several of the poems were inspired by the business that my mother and father owned and managed together for sixteen years, Savarese Pastry Shoppe. The business was all-encompassing, and my father especially was almost never home.

After many years of grappling with his emotional absence, the title poem of the collection came to me: while my father hadn’t been around enough to teach me what I needed to know, he gave bread the way he knew how. Many of the poems walk the tightrope between loss and longing, acceptance, and love. There are also several poems that I would classify as love poems—love poems to the Divine and also love poems to Brooklyn. I cherished growing up in a neighborhood where the church and the stores were named after legends like St. Bernadette’s Shrine Church, Joe Torre’s Sports Shop, and Mona Lisa Bakery, and where, by the time I was eight, I could walk everywhere by myself—to school, to Ciulla’s Salumeria where I picked up Italian and American bread, and to the Brooklyn Public Library where, in part, my love of stories began (see poem at end of interview).

After many years of grappling with his emotional absence, the title poem of the collection came to me: while my father hadn’t been around enough to teach me what I needed to know, he gave bread the way he knew how. Many of the poems walk the tightrope between loss and longing, acceptance, and love. There are also several poems that I would classify as love poems—love poems to the Divine and also love poems to Brooklyn. I cherished growing up in a neighborhood where the church and the stores were named after legends like St. Bernadette’s Shrine Church, Joe Torre’s Sports Shop, and Mona Lisa Bakery, and where, by the time I was eight, I could walk everywhere by myself—to school, to Ciulla’s Salumeria where I picked up Italian and American bread, and to the Brooklyn Public Library where, in part, my love of stories began (see poem at end of interview).

L’Idea Magazine: “Celibate: A Memoir” is your most recent book. The core of it touches a very delicate subject, your past relationship with a priest, but that is not really the main subject, is it?

Maria Giura: My past relationship with the priest is one of the main subjects and actually dominates much of the book, but you’re right that the subject matter goes deeper than this. The book is ultimately about my struggle to trust God, to understand Him as a loving Parent, who loves each of us unconditionally and cares about every aspect of our lives. For many years, I didn’t realize it, but I was walking around with an image of God as distant and detached. At times I even thought Him a cruel taskmaster. I struggled with being a single woman and thought God loved me less than He did other [women], that in some kind of way He was playing favorites. My image of God the Father was not unconnected to the characteristics I saw in my natural father who worked himself to the bone and had a complicated relationship with my mom.

So, the book is ultimately about this trifecta of fathers—my father, priest-father, and God the Father—and my struggle and drama with all three, as well as my shifting relationships and understanding of each of them. I could say a lot more, but I don’t want to give the book away.

L’Idea Magazine: I believe it shows a lot of bravery on your part to tell the world your story. Have you had any negative feedback on the memoir?

Maria Giura: A few family members were very upset with me. They thought I was too detailed about my past relationship with the priest but also about my family’s life when I was growing up. Judith Barrington, the author of Writing the Memoir, explains, “Autobiography is the story of a life; memoir is the story from a life.” I didn’t tell the story of my whole childhood. I focused mostly on the shadow side because it connected thematically to the rest of the story. From most of my extended family, there has been a good deal of silence around the book. They’ve said very little if anything to me about it. By living and writing my past, I had already processed it, but my extended family, and some acquaintances who were not aware of my story, were startled and uncomfortable by the degree of my candor and struggle. While I understand that it must have been difficult for them to read on a couple of different levels, the silence has been painful since, as authors, our books are our metaphorical “kids” who we pour our love into, who we’d like to be celebrated.

With this said, there have been more readers and reviewers than not who have been captivated and moved by the memoir and some who have even greatly related to it. A number of people commented on how it made them think more deeply about their relationship with God, which is the very best feedback I could possibly get. One of the best critical reviews the book has received thus far is from editor Michelle Reale: “Celibate not only captures a personal history but plumbs the depths of the question, ‘To whom do we really belong?’ I can’t put too fine a point on just how stunning, life-giving, and expertly written this memoir is.”

The lesson is: when you publish a highly revealing memoir, try not to have expectations about how your family, and others close to the story, will react; it could be too much for them.

L’Idea Magazine: You won awards for poetry from the Academy of American Poets, the Paterson Literary Review, and the Center for Women Writers. Do you define yourself as a poet or as a writer who also writes poetry?

Maria Giura: Tough question. I’d say I’d define myself more as a writer who also writes poetry. Yet, I’ve been writing poetry since I’m thirteen, and it’s the genre I keep coming back to, the one that brings me the most joy. If I publish a third book, it will likely be another book of poetry.

L’Idea Magazine: You also wrote for television. What did you write about? Do you have a major theme that you follow in your screenplays?

Maria Giura: I wrote profile segments for TV shows like New Morning, produced by Lightworks, Christopher Closeup (TV and radio), and Telecare TV, now Catholic Faith Network. I also did some writing for CBS Newspath. All three programs focused on individuals—sometimes celebrities—and organizations who were making a difference in a variety of fields. I loved researching and writing for these programs, which focused on inspiring, positive, and successful guests and/or messages. Writing for TV also really helped me become a better, more concise writer. Interview scripts can’t be long-winded; you have to get to the heart of the matter quickly. I’m really grateful for the writing lessons I learned in TV. A major theme that follows in all my writing—not just the writing I did for television—is spirituality and faith.

L’Idea Magazine: You taught Literature and Writing at various Universities. How rewarding is teaching these subjects? Is there a writer who you prefer and why?

Maria Giura: It was very rewarding, especially the upper-level writing courses. I really enjoyed helping students tap into their own stories and truth. We looked at the works of many creative nonfiction authors and memoirists to “listen” to their voices and study how they told/showed their stories. I met several good writing students whose stories truly moved and humbled me. What was most rewarding was that for some of my students, writing their stories was healing for them.

A few of the authors I prefer are Joann Beard, A. Mannette Ansay, Esmeralda Santiago, Louise DeSalvo, Mario Puzo, and the poets Mary Oliver, Maria Mazziotti Gillan, Richard Blanco, and Marie Howe; I’m sorry that I can’t narrow it down more! I tend to enjoy writers and poets who use their own past and youth to tell stories and who accomplish this without any sentimentality. I admire Mary Oliver and Marie Howe for their subject matters and sparse style; there is something sacred in nearly every one of their poems.

L’Idea Magazine: How much did being Italian American influence your life decisions? And your writing?

L’Idea Magazine: How much did being Italian American influence your life decisions? And your writing?

Maria Giura: My parents and their families immigrated from southern Italy, and both parents, especially my mother, believe that what happens in a family should stay in a family. She is a very private person, and, ironically I am too, but I had to depart from this Italian ideology in order to write Celibate and, to a lesser degree, What My Father Taught Me. I carry my family’s voices in my head, but I put them aside in order to write my story and tell my truth. Yet, I am deeply grateful for that same sense of privacy and modesty that my mother has always lived and has always taught my sisters and me to live. For one, it influenced how I wrote the revealing parts of Celibate, and it also affected my motivations and intentions for writing it. My purpose was not to scandalize or to hurt; it was to show on the page to the best of my ability the story that would not have left me alone if I had not figured it out on the page. Being an Italian-American (and practicing Catholic) woman has also affected my decisions regarding the promotion of my memoir. It has taken me this whole first year since Celibate has been published for me to become somewhat more comfortable with sharing and promoting it. I am still careful as to how and to whom I promote it.

It was also very important to me to show my and my characters’ “Italianness” on the page. Being Italian (American) is such a big part of my and many of my characters’ identities; it’s almost as close to my skin as my being a woman. I am so grateful to my grandparents, my mother, and my father for their nerve, their perseverance, and their labor to make life better for themselves and their children. It’s a legacy and a culture I’m so proud and thankful to be part of.

L’Idea Magazine: Do you have any new projects in the work?

L’Idea Magazine: Do you have any new projects in the work?

Maria Giura: I am sporadically working on a third book, which will be my second book of poetry. I am close to halfway done, but I suspect the second half will take me quite some time. I spent so many years and so many words writing Celibate that at the moment I feel a little tapped out. I’d also like to grow more as a poet before I put another book of poetry out, and I’d possibly like to experiment with some different subject matter than I have in the past.

L’Idea Magazine: If you had the opportunity to go back in your life to when you were a kid and re-live it, is there one decision that you would like to change?

Maria Giura: I don’t think I’d re-live any part of my childhood over again if given the opportunity. I really believe that everything that happened or didn’t happen helped shape me and gave me the joys and struggles that were supposed to be my joys and struggles. But I would go back to junior and senior years in high school and perhaps make some different decisions about higher education. I think in some ways being an Italian-American girl in Brooklyn in the 1980s helped me to play it a little too safe. I don’t think a lot of girls like me at the time were encouraged to choose from a wide range of colleges or to go away to college at all or to think more outside the box. I’m not positive that I would have listened to a guidance counselor or relative encouraging me to spread my wings, but at the very least it would have been good for me to hear. If I were to do it all over again, I would have looked at colleges out of state, especially Jesuit colleges. I would have challenged myself with more rigorous coursework and also classes I didn’t “need.” I think I was a little too practical for my own good.

L’Idea Magazine: Do you believe writers can be more useful than ever right now during this Covid19 crisis? If so, how?

Maria Giura: I do, because the pandemic has forced—and allowed—some of us to slow down and take stock. Some people have had more time and inclination to read and to watch programs and movies. I think COVID 19 has also given us the opportunity to be “deepened” by life. If we’ve taken to heart what has happened in the world and in our cities this year, then I think we’re living a little less on the surface. Good writing has the potential to move and urge someone in a way that simply telling them the “message” cannot. I also think we need many different writers, voices, and genres to help document and give a compassionate and wise testimony. I just watched the season premiere of a show, and they addressed both the racial murders and Black Lives Matter as well as the pandemic. They showed how some families—even interracial families—find it difficult to talk about race. I don’t think a writer can, or should, write a story about something taking place in 2020 and not acknowledge both.

L’Idea Magazine: Is there an unachieved goal at this stage of your life that you feel you could eventually accomplish? Any dreams?

Maria Giura: One of my biggest dreams is that Celibate gets its legs and reaches many more people. It’s not something, though, that I can accomplish entirely on my own. It would need divine intervention. I feel that the story has something in it for so many people and that it would translate beautifully to the “big” screen.

L’Idea Magazine: A message for our readers?

Maria Giura: Do not give up on your labor of love. It can potentially take a very long time for your vision to materialize, and people may not understand, but if something is supposed to be born through you, in the end the reward of seeing it through outweighs the frustration and sacrifice of having stayed the course to make it happen. My memoir took me more than thirteen years to finish. There were days when I didn’t think I could finish it or whether it’d be worth it, but I know that if I had let it slip through my hands, if I had taken the easy way out, it would have been the biggest regret of my life and that would have been a very unpeaceful, unhappy thing. Make what you’re supposed to make; finish what you’re supposed to finish. It may not gain you money or friends, but you will have made what only you—you—could make, and there is big peace in that.

What My Father Taught Me

My father never taught me

how to fish or play ball or dance,

how to do repairs in the house

or talk to a repair man

so I wouldn’t get taken for a fool.

He never taught me how to change oil

or a tire or even windshield wiper fluid.

He never read me a bedtime story

or asked me about school.In the morning when I sat on his lap

he’d kiss my hair and call me Bella,

but when I tried to tell him something,

he’d look at the clock,

jump up and nearly drop me.

After he and my mother separated,

when it was his day to take me and Annie

he’d sometimes cancel,

leaving us in our dresses and barrettes,

holding hands.I’m not sure I can finish this poem.

What do fathers teach their daughters?He gave what he could: headlock kisses,

18 karat gold,

the newest electronic gadgets.

He wrote to us on layered birthday cakes

he made with his hands,

our names in delicate pink icing

in his squared European handwriting.

He held me high in his arms

on that one vacation to Italy with my mother

when I was four and clung to him

in St. Mark’s Square

afraid of the pigeons;

held his hand on my leg

when I was atop an elephant at the zoo,

my lips pursed with fear.Years later, whenever I visit him

and my step-mother, he always asks me,

“How’s the car running?

How many miles?”

To this day, he brings my mother

sfingi and zeppole on her name day,

loaves of bread and seven-layers

anytime he’s in the neighborhood,

asks me when I speak to him on the phone,

“How’s Mamma?”The same bakery that stole my father from us

gave me a man

who could pay attention long enough

to make something beautiful,

who helped me to

grow upand write about him.

(From “What My Father Taught Me”, Bordighera Press, 2018)