Interview by Tiziano Thomas Dossena

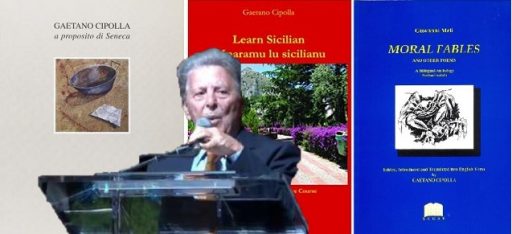

The volume “Siciliana: Essays on the Sicilian Ethos”, 2005 represents the most important contribution of Gaetano Cipolla to the study of Sicily and Sicilian culture. The work contains various essays already published and many other unpublished ones aimed at defining Sicilianity through a study of Sicilian history and literature.

His interest in Sicily and the Sicilian language led him to collaborate with J.K Bonner for the “Introduction to Sicilian Grammar”, which represents the first work of its kind in America. Professor Cipolla edited the volume and published it in 2002.

Gaetano Cipolla: Before devoting myself to Sicilian culture, I had already reached the rank of Associate Professor at St. John’s University and I was interested in topics that had nothing to do with Sicily. The book Labyrinth: Studies on an Archetype contains essays of literary criticism based on the writings of C.G. Jung, E. Neumann, and other scholars of Depth Psychology. My Ph.D. degree was entitled “The Archetype of the Labyrinth and Its Manifestations in Petrarch”. The essays published in that book derive in part from the dissertation, but I also added other studies of Jungian criticism on the figure of Ulysses in Dante’s Inferno and on the presence of the labyrinth in Pirandello and Calvino.

L’Idea Magazine: While collaborating with various Italian magazines, in 1978 you were co-editor of “La Parola del Popolo,” the oldest Italian language magazine in America. How did this adventure of yours, which lasted a good six years, come about? What happened to the magazine?

Gaetano Cipolla: I worked with Egidio Clemente, an old trade unionist who worked as a typographer. La Parola del Popolo (The Word of the People) was the official organ of the American Socialist Party, founded in 1907. I wrote literary articles, some editorials, and helped Egidio with proofreading. The magazine lasted until 1984 when Egidio, who was the soul of the magazine, passed away.

Gaetano Cipolla: Italian Journal was an important magazine on Italy edited by Vittorio Tesoro. My responsibility was to compose the Journal typographically, although I also wrote some articles and reviews. It was the time when we began to use the computer to layout and design magazines and having acquired a certain skill with composition programs such as the old “Ventura Publisher”, I designed and composed the journal typographically and wrote some articles and reviews of books.

The brochure What Italy Has Given to the World was born as a presentation to the students of the Italian club at the University. I asked myself the following question: “What would be missing from the world today if the Italian peninsula had not emerged from the Mediterranean Sea?” The answers between joking and serious offer readers the vast contributions to Western civilization made by the peoples who have inhabited the Italian peninsula. For example, America would lose its name, a thousand American cities bearing Latin or Italian names would disappear. The booklet, which was first published in the Italian Journal was printed as a booklet later and was very successful. NIAF ordered two thousand and five hundred copies. In fact, they used it as an incentive to motivate people to join NIAF by offering the book for free to new members. Other associations, such as “The Sons of Italy”, have ordered thousands of copies. The brochure still sells. The other day the Garibaldi and Meucci Museum ordered 25 copies. In all, we have sold more than 25,000 copies.

Gaetano Cipolla: I wanted to go back to my Sicilian roots and realized that as an immigrant at a certain point you are neither Italian nor American. Going back to Sicily I was regarded as American and in America was not really American. I wanted to reclaim my identity as a Sicilian. My interest in Meli was natural. He was not only the greatest Sicilian poet, but he expressed the essence of the spirit of Sicilians in his works. Meli, as Giuseppe Pitrè said, “was the most perfect embodiment of the ideals and aspirations of the upper and middle class of the eighteenth century, and also the most outspoken painter of the customs of the time … who deplores the miseries of the times.” In his works, he expresses the permanent contrast in his spirit between idealism and skepticism. His Don Chisciotti and Sanciu Panza is, in fact, a projection of the dilemma that raged inside of him. It embodies the idealism of Don Chisciotti who hoped for a better world for the poor Sicilians, who carved on a tree trunk his ideas for a more equitable distribution of wealth, a better application of justice, a need for universal peace, but it also embodies the skepticism of Sanciu Panza, who believed only what he could touch with his hands, who knew from experience that the Sicilian status quo would not change. The contrast between the two tendencies of the Melian spirit was ultimately won by Sanciu, who was the true protagonist of the poem, not Don Chisciotti, whose praiseworthy ideals are ridiculed by the squire as the delusions of a madman. Sanciu wrote the following epitaph on his master’s tomb:

La cinniri ch’è sutta sta balata

Fu spogghia d’un eroi di desideriu;

chi mai sappi cunsari na nzalata,

non ostanti pritisi in tonu seriu

di cunsari lu munnu…

The ashes that lie under the slab of stone

Are the remains of one who would be hero

Who never knew how to fix a salad

And yet pretended he could fix the world.

In the afterlife, for his folly, Don Chisciotti is condemned to gather the wind with a net for six months and as a reward for his saintly ideals spend the other six months in the Elysian Fields, while Sanciu earned a place among the philosophers. The Don Chisciotti and Sanciu Panza is different from Cervantes’ Spanish model. In this work, we see how times have changed and how eighteenth-century Sicily is different from Cervantes’ Spain. It is a work of twelve Cantos and a Vision that I tried to re-evaluate even from a critical point of view in the introduction.

L’Idea Magazine: Your first work of translation into English was L’origini di lu munnu, (1985) by Giovanni Meli, published by Arba Sicula. Why did you choose this book to translate?

Gaetano Cipolla: L’origini di lu munnu is a delightful, satirical masterpiece in which the poet imagines Jove, the father of the gods, in conversation with his children while exploring how to create the world that did not exist “at the time when time was yet not time”. The Olympians offer their opinions on how to create the world, but Jove ridicules them. In the end, he understood that the only substance that existed was himself and he asked his children to tear him apart and use his body parts to create the world. Thus, one of his legs becomes the Italian peninsula and the head becomes Sicily!

Gaetano Cipolla: According to some, Favuli morali is Meli’s masterpiece. The fables are the fruit of a scientist who knows the world deeply. By making the animals speak, Meli could say what he thought without fear of the social repercussions he would have been exposed to if he had said them in the first person. Meli did not moralize as La Fontaine does, for example, but through what animals do and say, the moral lesson becomes transparent, like the case of the crab who wants to teach his children to walk straight while he cannot teach them by example.

I translated the 89 fables using the metric scheme of the originals. This requires great efforts to find the right rhymes without damaging the fluency of the language. In some cases, the fables are written in terza rima, like Dante‘s Divine Comedy, requiring even greater effort. These fables are little masterpieces that fully convey Meli’s wisdom.

Gaetano Cipolla: This anthology contains Meli’s most important works in bilingual format. I also included a chapter of nearly one hundred octaves of the Don Chisciotti and Sanciu Panza. It is a large volume that gives the reader the most beautiful pages of this brilliant Sicilian poet who deserves to be better known in America. Meli was a scientist (he was a doctor) and professor of chemistry at the University of Palermo as well as being an exquisite poet. Many consider him an Arcadian who was interested in shepherds and shepherdesses, while he was actually a man of science who knew how to evaluate reality. Pirandello, who knew Meli’s work very well, rejected the view that is fellow Sicilian was an Arcadian, adding that Meli possessed all the instruments of poetry in his hand and not just the shepherds’ flute.

Gaetano Cipolla: Knowing that I was interested in Sicilian literature, the editors of the Dictionary asked me to write a profile on the plays of Martoglio and Brancati. In the case of Martoglio, I had already published The Poetry of Nino Martoglio, an anthology from his popular collection Centona.

I founded a series of books entitled “Pueti d’Arba Sicula / Poets of Arba Sicula”, whose objective is to make known the best of poetry written in Sicilian because I am convinced that poets are actually the best ambassadors of a country. I’d like to point out that for this series the introductions and translations into English are almost all mine. (In addition to Italian language and literature, I also taught courses on the art of translation at St. John’s University.)

You asked me why I chose Veneziano. Antonio Veneziano was the greatest Sicilian poet of the Renaissance and was known as the Sicilian Petrarch. When people heard a particularly beautiful poem and did not know who the author was, they automatically attributed it to Veneziano. He was a great defender of the Sicilian language, saying that being Sicilian he did not want to become a parrot by repeating the language of others. And so he wrote in Sicilian even though he knew how to write in Latin and Italian. An extraordinary character for many reasons!

Gaetano Cipolla: Arba Sicula was founded in 1979 by a group of Sicilian-Americans such as Joseph Polisi, Gaetano Giacchi, and Alissandru Caldiero, who wanted to give a different image of Sicily and Sicilians from the stereotypes seen on American TV and cinema, and to rediscover truer cultural values shared by Sicilians, as well as to highlight the island’s contributions to Western civilization. At first, my role was marginal, but I participated in the activities promoted by the group. Then, as my interest in the Sicilian language and culture grew, I began to contribute more consistently and in 1976-7, when the association was in crisis, I agreed to become Editor of its publications, and then President.

Arba Sicula published the first and only English-Sicilian-English Dictionary (by Joseph Bellestri), the first Sicilian grammars by Joseph Privitera and Kirk Bonner, and then my Learn Sicilian / Mparamu lu sicilian, conceived as a textbook that uses modern pedagogy for teaching foreign languages. The success of this volume convinced me to write Learn Sicilian II, just published. This volume is written in Sicilian because it assumes that students have already acquired a basic knowledge of the language. It is equivalent to the second year of study at the university level. On November 30, 2021, I will present the book to the Columbus Foundation.

Gaetano Cipolla: In this country, there are many Sicilians. I would say that 40% of the Italian-American population has its origins in Sicily. The first generations of emigrants have now disappeared, but the children and grandchildren have a great interest in discovering and understanding the culture in which they participate because of their grandparents and great-grandparents. Unknowingly, they live that culture they have absorbed by osmosis by living in a Sicilian environment in the family. The same for the language they must have heard growing up. Arba Sicula offers them the opportunity to explore why they act in a certain way. Reading my pamphlet What Makes a Sicilian? an American woman married to a Sicilian once told me verbatim, “Now that I’ve read your book, I understand my husband much better.”

Arba Sicula plays an important role for Sicilian immigrants, introducing them to Sicily. It sounds strange but it is true. The emigrants of the past two centuries, leaving for America, did not know Sicily. They knew their town and perhaps the neighboring ones, but not Sicily. Once, an immigrant from the Bronx who came with us on one of the first tours of the island, said to me, “Thank you for showing me the beauty of our island that I did not know at all!” Every year he returned to Casteldaccia near Palermo and stayed there for a month without visiting other towns. Another Sicilian tourist from California, after taking the tour, gave me a small silver sailing ship bought in Taormina, saying, “Thank you, I learned to understand who I am by reading your books.” Appreciations of this kind usually embarrass me, but I accept them because they are sincere. Almost all those who send me the check to renew their subscription write phrases like this: “Thank you for defending and keeping up the Sicilian language and culture!”

There is, evidently, a great deal of interest in this topic …

Gaetano Cipolla: The booklet is offered to all new members of Arba Sicula. I tried to explain to myself what it means to be Sicilian. Obviously, a booklet of just thirty-two pages cannot hope to define a people that has three thousand years of complex history behind it, a people that has suffered the presence of many foreign peoples attracted by the beauty and wealth of the island. Seventeen different dominations have left visible traces in the Sicilian DNA and on their behavior; the Greeks, the Romans, the Arabs, the Normans, and the Spaniards. Everyone left something, but without altering the physiognomy of Sicilians that much. Already in 424 BC, Hermocrates of Gela claimed the Sicilian character of the island’s inhabitants, who had by then emancipated themselves from Greece by saying, “We are neither Doric nor Ionians, we are Sicilians!” The booklet is more my personal view of the Sicilians, but apparently shared by many since many order it. The booklet is also included in the volume Siciliana: Studies on the Sicilian Ethos, which contains chapters on the relationship between Greece and Sicily, the drama of the Jews in Sicily, a history that few know, the Arabs and their importance, and other essays.

L’Idea Magazine: You founded an international publishing house (“Legas”) whose main purpose, at its inception, was to publish books that have a link with Sicily and its people. When did you come up with this idea? In those years in which you made this decision, did you imagine that you would be so successful in such a limited editorial niche?

Gaetano Cipolla: With this series, I wanted to give Sicilian writers the opportunity to tell their story, instead of reading non-Sicilian writers who write about Sicily. The latest book published was published by Mark Hehl and is called Ameri-Sicula: Sicilian Culture in America. In it, about thirty Sicilian-American writers tell their experiences.

The Idea Magazine: “Learn Sicilian / Mparamu lu Sicilianu” is a university textbook written by you. How was it received?

Gaetano Cipolla: The book has been very successful in the United States. We are already at the third reprint. It has also been translated into Italian by prof. Alfonso Campisi, who is using it in his courses at the University of La Manouba in Tunis, where there is a large colony of Sicilians. Learn Sicilian / Mparamu lu Sicilianu is also used in America as a textbook at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia. Italian Charities of America has adopted it for its courses on Sicilian.

Gaetano Cipolla: I had never written anything in Sicilian before Andrew Liotta asked me to write a libretto using the plot of Giovanni Verga’s short story “La Lupa” as a basis. I wrote it in one evening, naturally returning to polish it and make it consistent with the composer’s needs. Liotta set the opera to music and we were able to present some arias in concert at St. John’s University. Unfortunately, Liotta passed away and I don’t know if I will ever have the pleasure of seeing it performed in the theater.

L’Idea Magazine: Certainly all the awards received are pleasing, but of the numerous awards they have conferred on you, which one was the most significant for you as a Sicilian? And as a teacher?

Gaetano Cipolla: I have received many awards for my work in favor of Sicily and for teaching, but I don’t want to identify them so as not to show off. The greatest reward I retain is the affection and esteem of my students who are happy to see me when I meet someone at an event.

L’Idea Magazine: You conduct an annual tour of Sicily for 35-40 members of Arba Sicula, which the virus has clearly not allowed you to do in the last two years. What does it consist of? A rediscovery of their region for Sicilian-Americans?

Gaetano Cipolla: Sicily is the best-kept secret in the world. That is, Sicily has so many beauties that, due to the continuous negative campaigns on the island, have remained unknown. Arba Sicula has tried all these years to give its members the opportunity to discover and become aware of the variety and natural, architectural and cultural richness of the island, and I am proud to say that all those who have taken the tour with us have become little ambassadors, multiplying among their acquaintances the positive feeling they had personally felt. Obviously, I don’t want to say that the credit for the increase in tourism in Sicily belongs to Arba Sicula, but we certainly contributed to the discovery of the treasures of Sicily. On our first tour, there was only one bus in the Segesta parking lot: ours. In recent years, the bus has to stop on the road because there is no more space for the bus to park.

L’Idea Magazine: Could you define the term Sicilianity?

Gaetano Cipolla: The term “Sicilianity” is by no means easy to define. If it were, I wouldn’t have written thirty-two pages to try and explain it to myself. Sicilians are complex people and when one believes that he has found the key to uncover the mystery, situations arise in which the key no longer works. Try reading What Makes a Sicilian? You will have an idea of the things that Sicilians consider important in social behavior, but all without categorical or prescriptive claims.

L’Idea Magazine: Could you tell us about “Casa Sicilia”?

Gaetano Cipolla: It was a good initiative that unfortunately ended badly.

Gaetano Cipolla: The publisher of Nuova Ipsa in Palermo had begun a project to publish critical editions of the work of Giovanni Meli (1740-1815) in eleven volumes. My task was to edit the three volumes dedicated to his Lyrical Poems. Lirica I has already been published, Lirica II is waiting to be printed. The complete text is already in the hands of the publisher, but unfortunately, he died last month. Now I don’t know if the project will be continued or not by his successor. We will see. In any case, I hope to be able to complete the work begun by publishing the third volume of the Lirica as well.

L’Idea Magazine: If you could meet any character from the past or present, who would it be and what would you like to ask him (or her)?

Gaetano Cipolla: The authors that I care about have already spoken at length through their books. Everything they had to say they have already said.

L’Idea Magazine: Do you have any other literary works in progress at the moment?

Gaetano Cipolla: It is a project that unfortunately is very difficult if not impossible. Last week I spoke via Zoom at a conference organized by the Sicilian Academy of Palermo on my efforts to restore the Sicilian language to the texts of the Sicilian School that flourished under Emperor Frederick II. As you know, the original lyrics have all disappeared except one song by Stefano Protonotaro. We are left with only some codes transcribed by Tuscan scribes who have made not a simple transcription but a real translation from Sicilian to Tuscan, changing the rhymes, often altering the meanings. Since we cannot go back to the original texts, I decided to do what the copyists did, that is, to retranslate their translation. I made three experiments with texts by Giacomo da Lentini, the inventor of the sonnet. I include a beautiful song by Giacomo in the new Sicilian guise and my English translation. Since space is not a problem, I include my translation as well:

Miravigghiusamenti

Miravigghiusamenti

‘n amuri mi distrinci

e mi teni ad ogn’ura.

Com’omu poni menti

in àutru esempiu e pinci

la simili pintura,

cussì, bedda, facc’eu,

ca ’nfra lu cori meu

portu la to figura.

‘N cor pari ch’eu vi porti,

pinta comu pariti,

e non pari di fori.

Deu, com’ mi pari forti

non so si lu sapiti,

com’ v’amu di bon cori;

ch’eu sù sì virgugnusu

ca pur vi guardu ascusu

e non vi mustru amori.

Avennu gran disiju

dipinsi na pintura,

bedda, vui sumigghianti,

e quannu vui non viju

guardu nni dda figura,

pari ch’eu v’aggia avanti:

comu chiddu chi cridi

salvarisi pir fidi,

ancor non vija inanti.

In cori m’ardi dogghia,

com’om chi teni focu

nni lu so senu ascusu,

e quannu chiù lu ’nvogghia,

allura ardi chiù ddocu

e non pò stari nchiusu:

similementi eu ardu

quannu pass’e non guardu

a vui, vis’amurusu.

S’eu guardu, quannu passu,

inversu a vui no giru,

bedda, pir risguardari;

annannu, ad ogni passu

e jettu un gran suspiru

ca facimi ancusciari;

e certu beni ancusciu,

c’a pena mi canusciu,

tantu bedda mi pari.

Assai v’aggiu laudatu,

madonna, in tutti parti,

di biddizzi c’aviti.

Non so si v’è cuntatu

ch’eu fazza zo pir arti,

pir cui vi nni duliti:

sacciatilu pir singa

zocch’eu no dicu a linga,

quannu vui mi viditi.

Canzunedda nuvella,

và canta nova cosa;

lèvati di maitinu

davanti a la chiù bedda,

ciuri d’ogn’amurusa,

biunna chiù c’auru finu:

«Lu vostru amuri caru,

dunatilu ô Nutaru

ch’è natu di Lentinu».

Extraordinarily

Extraordinarily

A love constrains me so

it never lets me go.

Like one who puts his mind

to paint a likeness of

a model he can view,

that’s all I do, my love,

I carry in my heart

an effigy of you.

I bear you in my heart

painted as you appear

but this outside won’t show.

God, it is harsh, severe,

not knowing if you know

that my love is sincere.

However, I’m so shy

I watch you on the sly

and hide the love I bear.

Moved by a strong desire

I drew a lovely portrait

that close resembled you

and when you’re not in view

that image I admire

and think I’m seeing you.

Like someone who believes

his faith can save his soul

though he can’t see that goal.

There’s burning in my heart

like one who has a fire

that’s hidden in his breast,

and when incitement soars

the flame grows even higher

so he can’t take much more.

That is the way I burn

when I pass by and turn

away from you, my love.

If when I pass, you’re there,

I do not turn to stare,

my love, to better see,

but with each step I try

I breathe a heavy sigh

that takes my breath away.

I feel then so unsteady,

who I am I can’t say,

so fair you seem, my Lady.

Much praise did I accord,

Lady, to you for all

the beauties you possess.

I know not if you’ve heard

it’s done with craftiness

that’s why you hide from view,

but take this as a clue

of what I’ll say to you

when you and I will meet.

My little novel song,

go sing of something new.

Rise early in the morn

and seek the fairest one

among the best in love,

whose hair is fine-spun gold.

“Your love that is so rare

give to the Notary

who’s from Lentini born.”

L’Idea Magazine: A message for our readers?

Gaetano Cipolla: I hope they can appreciate Sicily for what it really is: an island to love. I conclude with a little gem from Giovanni Meli, which gives an idea of the lightness of his verses and the difficulty that translation entails:

LA VUCCA

Ssi capiddi e biundi trizzi

sù jardini di biddizzi,

cussì vaghi, cussì rari,

chi li pari nun ci sù.

Ma la vucca cu li fini

soi dintuzzi alabastrini,

trizzi d’oru, chi abbagghiati,

perdonati, è bedda chiù:

Nun lu negu, amati gigghia,

siti beddi a meravigghia;

siti beddi a signu tali

chi l’uguali nun ci sù.

Ma la vucca ’nzuccarata

quannu parra, quannu ciata,

gigghia beddi, gigghia amati,

perdonati, è bedda chiù.

Occhi, in vui fa pompa Amuri

di l’immensu so valuri,

vostri moti, vostri sguardi

ciammi e dardi d’iddu sù.

Ma la vucca, quannu duci

s apri, e modula la vuci,

occhi… Ah vui mi taliati!…

Pirdunati, ’un parru chiù.

The Mouth

Oh, those braids of golden hair

are a garden sweet and fair;

they’re so beauteous and rare

none comparison will dare.

But the mouth with eburnine,

pearly teeth so neat, so fine,

Golden Braids that all outshine,

please don’t mind, ’tis more divine.

My dear brows, I can’t deny

you’re as lovely as the sky,

you’re so lovely to the eye,

all who see you simply sigh.

But the mouth’s a sugar beet

when she opens it to greet,

lovely brows that love entreat,

please forgive me, ’tis more sweet.

Love has chosen you, dear eyes,

just to flaunt his greatest prize.

All your actions, all your sighs

represent his flames, his guise.

But the mouth I so adore

when her words begin to pour.

Lovely eyes, why do you stare?

Please forbear … I’ll say no more.