Interview by Tiziano Thomas Dossena

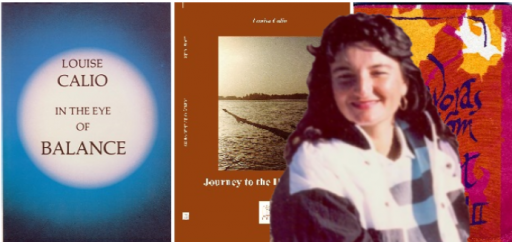

Director, author, and performer of multi-media performances set to dance and music by jazz composers, Oliver Lake and Leo Waddah Smith, she was Founding member and first Executive Director of City Spirit Artists, Inc. (1976-1981). She has a BA in literature, Magna Cum Laude with Special Honors in English from SUNY at Albany and a Masters from Temple University and is a Certified English and Yoga Instructor. Louisa was the Director of the Poets and Writers Piazza for Hofstra’s Italian Experience for 2001–2013.

Her writings appeared in numerous anthologies & journals. She has traveled to East and West Africa, Europe, and lived in the Caribbean, exhibiting her photos with her poems in a “Passion for Africa” and “Art of the Word, A Passion for Jamaica I and II.”

L’Idea Magazine: Louisa, what inspired you to get involved in the artistic world in general, and in poetry in particular?

Louisa Calio: What an interesting question. My first piece of art was a drawing of a boy on a bicycle that won a citywide competition in Brooklyn, New York, when I was 5 years old. I attended PS 95 for one year before being sent to parochial school. That drawing at the time seemed to come to me out of the blue, until I later learned when I was 1, my mother left the house with me in her arms, fell on the steps and a boy on a bicycle hit us. My head hit the concrete fracturing my skull. I now believe, this was the way I processed a trauma, transforming a destructive experience into a creative one, as art can do.

Later on that year, I was transferred to Catholic School. My nun asked me to do the introduction to the Christmas play as well as dance. I can recall the first waves of love I felt as I looked at the audience searching for my parents before beginning my speech. You could say these two events prefigured my journey. I loved dancing, especially in my grandfather’s garden, where I sometimes heard and saw fairies. I read avidly, even as a child, and made little plays with neighborhood friends, as well as rituals to the sun. Catholic school could feel oppressive and confining. In third grade, I had a terrible experience with a sister who seemed to love to torment children. To comfort myself, I memorized John Donne’s poem, “No Man Is an Island” and found the words of poets were healing, musical, and profound. I lived around opinionated philosophers in our family and was already serious enough to question the need for human suffering. At 8 years old, I confessed to being a heretic…a long story which is all included in my novel Lucia Means Light.

My Grandparent’s duplex was a hotbed of divergent and passionate political and social opinions as well as profound silences. The main character in my novel is associated with Santa Lucia, the symbol of illumination and compassion. I called our family a “tribe” In many ways, it operated on a tribal structure with extended family living upstairs and next door and down the street. When there was a financial problem, Grandfather was relied upon. He was highly disciplined and financially stable even in the depression, because he made fine furniture for the wealthy, a job he did not relish, later opening his own business with his sons. A communal energy pervaded the household where elders came and went. I felt free to offer opinions with absolute authority too even when ignored.

However, the old hierarchy of respect for a single chief or male shaman was crumbling. My mother came from a generation of women who were not satisfied with the role of householder. She seemed to sense it was time to seek power from another base beyond mothering. I had many talented aunts as well. My Aunt Anne, actually I had two, both gave me books to read since I can remember. My mother’s half-sister Anne encouraged my creativity and sense of adventure. She had no children and traveled the world. My paternal Grandmother played piano and her daughter sang opera. My parents loved music and we had quite a record collection. When I wasn’t making up a musical or reading poems, I found the voice of poets spoke to me beyond the surface offering a depth I longed for. Yet, it was my mother Rosa who was the storyteller and a primary inspiration. Rose Calio born Rosa Marchesani, May 23, 1922 in Brooklyn, NY was my confidant. Being the eldest, she treated me like her best friend. She shared her fantasies and romantic dreams of lost loves and possibilities. She shared with great feeling. I sensed my mother’s hunger for life. She never lacked for an opinion or the facility with which to express it. Unlike most of our family, she was at ease with sharing intimate details and feelings in the English language and openly expressed her thoughts on most topics sometimes much to the dismay of others. She loved to read and point out lessons. This gave her a certain power over me as I willingly offered my ear and empathy to what I would later call her feminine bias. Yet, despite Rosa’s verbal bravery and aptitude, when a real struggle or confrontation ensued, she could be reduced to tears. Later those tears turned to sadness, depression, and illness.

In the opening pages of my manuscript Lucia Means Light the heroine of my novel expresses her mother’s influence as well as what she sees is a pattern manifesting in her lifetime:

“Like many women of my generation, I was destined to be my mother’s ambassador to the larger world, and although I’ve never been able to get her to admit this openly, I feel I am my mother’s prodigy. She, along with my maternal grandmother, raised me, while my father and grandfather spent the larger portion of their time working, sometimes late into the evenings. Although I do not in any way feel this diminished their deep imprint on me, I believe it gave my mother an ability to understand and forgive some of my choices and excesses. I am the only one of her three children who strayed so far from the nest, and being first, grew up during the early part of her married life when she most longed for freedom and adventure, which her role as an Italian American wife and mother did not allow for.”

Poetry is a way of knowing, much like dreaming, and a poet/artist often lives at the borders of internal experience and outer revelation. She values the inner and the imaginary because it is the source of creativity and a greater more universal truth. I needed a broader vision to bring the seeming impossible polarities I lived around in my life. Poetry explores the far reaches of the psyche, a depth of feeling in a heightened language carried by the breath. At its best, we can call poetry a language of the soul. Many women wrestled with issues of soul proportion in our time. After two thousand years of patriarchy, a history marked with periods of persecution, witch burnings, torture, severe punishment and repression of women and all dark others, the silence of repression was about to be broken wide open.

L’Idea Magazine: You appear to stand by your Italian American heritage while developing at the same time interests in other cultures. How strong was the influence of your Italian family on your work and career choices?

Louisa Calio: My Italian-Sicilian heritage was the cauldron from which my life and work emerged. I came from both an artistic and practical family, who like many Italians arrived in America to make a better life. They worked hard to do so and often had to overcome great losses. Both my maternal Grandparents lost their spouses in the 1918 pandemic, before meeting and marrying. Each had children from the previous marriage. Coming to America meant they had left some of their family behind. My Grandfather left his parents at age 14. He left the land he knew, the language, and a language of feeling repressed in order to survive and fit into a foreign culture with a complex history of slavery, Native American abuse, and British roots. Sometimes those stuffed feelings erupted in terror or rage. I believe poetry was my way of exploring and reclaiming those lost feelings and parts of the self and sometimes transforming them.

Although my father wanted me to be a lawyer and my mother Rose hoped I would be a teacher, I was drawn to the literature and the creative. I grew up with the sound of opera, thanks to my Grandfather Rocco Marchesani’s passion for it. We lived in my Grandparents’ home filled with art work, fine furniture and sculpture he created, until I was 7 years old. Grandfather was sub-contracted by D.H. Lavezzo & Sons, a well-known antique dealer in Manhattan and several interior designers before opening his own business. As a result, his works are in Vizcaya, the Rockefeller collection, churches, and the homes of some famous stars. He created a bed-head for Marilyn Monroe, the new Mrs. Arthur Miller, before having a stroke. People joked that it was meeting the diva that caused it. Pop, as they called him, taught himself to draw and sculpt all over again with his left hand. I was by his side when he died at Coney Island Hospital. I heard him say to the young doctor who wanted to revive him, “I have worked since I was 9 years old, go save somebody else!”.

My maternal Grandmother Angelina, known as Angie, nourished us with more than food. She had a wisdom, a joy and worldliness that was rare. She was a suffragette and raised in the Protestant faith, when her father, disillusioned with how Italians were treated by the Catholic Church, converted and joined the mission of the Salvation Army. Those years with our family in Brooklyn were the happiest days of my life. The melting pot of Italians from all over Italy and Sicily as well as many others who visited around our kitchen table in Gravesend, offered my eager and open mind a rich array of opinions, ideas, and thoughts. People who likely would never have met in Italy, met and married in America. Debates about world affairs, concerns for the poor and oppressed were often a regular meal there. In a recently published essay in the anthology edited by Mark Hehl, Ameri-Sicula, I put it this way:

“I like to think of my American self, the persona born and raised in Brooklyn, New York, as a metaphor for my spirit, while the part of me that lived at home was my soul. Growing up in Brooklyn, in the 1950s in my Grandparents’ Italian home was quite a mix. While my intimate world had many Italian customs, beliefs, and traditions, I also had Howdy Doody, Davy Crockett, Mickey Mouse, and all the dreams of post World War II American children. To boot, I was born on the 4th of July, which many in my family considered a good omen. I lived near the Statue of Liberty and loved the American hero, Superman. I sang songs my father brought home, like “Old Soldiers Never Die” and “Jimmy Crack Corn”. I owned the first Howdy Doody Puppet in my neighborhood and felt part of an old frontier I had never seen with a Davy Crockett coonskin cap, as well as battles for and against an England I did not know. Not until I was in college in the late 1960s and grad school in early 1970s, did I feel the need to explore and actualize a part of my being that had little connection with this frontier tale. It identified with darker others, their struggles, rituals, with the ways of people like Native Americans and African Americans, as well as journeys to the African continent.”

My Father Joseph Calio, whose parents left Sicily for New York in 1910, grew up without his father, Antonino, who died suddenly from pneumonia when my father was 12 years old. My Grandmother Luigia went to work in the clothing industry in Manhattan after his death. She was a pattern maker and did designs for women’s lingerie. My father joined the clothing industry after he returned from serving in War II. It was a fierce and difficult industry. His road wasn’t easy. He began as a contractor, lost his business during a downturn, and had to start over. He worked his way up the ladder with top designers like Patty Capelli, Vera Maxwell finally becoming vice president of Ralph Lauren’s Women’s wear until he died suddenly at 66. He worked his whole adult life, provided us with a comfortable life and many beautiful things. He was committed to our heritage and served on many boards, was VP for AID (Americans of Italian Descent) with Senator Fred Santangelo and. often present at my productions, even bringing audiences from New York to Philadelphia and New Haven. I believe I got my production skills from him.

There was also a numinous dimension throughout my life since childhood, telling me things, offering comfort when needed, speaking or “channeling” voices and memories of my ancestors, my ancient bones, the DNA, which may best be expressed as “the dark mother” defined by the works of women writers in SHE IS EVERYWHERE gathered by Dr. Lucia Chiavola Birnbaum, a Sicilian American author I would meet and befriend. Sometimes a sprite appeared in my Grandfather’s garden to my mind’s eye when I was a child and played among the basil plants and mint leaves. She told me about nature and became the voice in many of my poems including “Signifyin Woman” and Isis. My mother’s half-sister Aunt Anne was the only one who knew about my experiences and never discouraged or scoffed at them. They were our little secret.

The dark mother was a large enough container to encompass all of our stories and sources that go beneath the surface to our roots and the archetypal patterns we interact with as we create our lives. I wanted to write about those patterns and the redemptive aspects of our stories, and not just repeat the past which was so painful sometimes. I sought to examine the deeper causes and meanings behind the outer play and dramas. I traveled to California to study with Brugh Joy MD a teacher, healer, and spiritualist who worked with groups in a way I am yet to fully describe. He and David Spangler and Robert A. Monroe were teachers of consciousness and offered tools to help harness and channel some of the energies unleashed in my journey.

My paternal Sicilian roots were shaped and penetrated by 16 nationalities, as scholar Gaetano Cipolla wrote in What Makes a Sicilian? Those aspects offered me untold wealth to drawn upon often unconsciously, as well as huge conflicts within. Sometimes I could feel the Greek woman performing in the amphitheater when I did a ritual, or another aspect who wanted me to keep silent, remember omertà and the danger of a woman showing herself. Sometimes this conflict held me down and back. I can’t separate my choices from all that nourished them. I feel I was blessed by a complex household and luckily didn’t end up skitzo. My Grandfather was a radical agnostic, naturalist, but very traditional in gender politics. My Grandmother a pagan of sorts whose father converted to Protestantism. My father’s family were strict Catholics.

L’Idea Magazine: Louisa, you are first of all a poet. Your first book was in 1978, your second one in 2014. I read that you have appeared in many anthologies and magazines. Why so much time between these two poetry books?

Louisa Calio: To be honest my life of adventure, soul searching, travel and spontaneity, didn’t leave much room for making publishing contacts, especially for books of poetry which were often accompanied by photos I took. At one point, I considered getting a Ph.D. to be in a community of scholars, but I felt after due consideration, that might stifle my own creative work and freedom to travel. I was fortunate to live a few blocks from Yale and had many good friends who were artists and scholars there, like Rudolph Byrd, Robert Stepto, and mentors Robert Farris Thompson and Henry Louis Gates, Jr. & others. There were many artists and educators that I hired and worked with in New Haven at the time. Sometimes I would send my work out to contests, but that was like trying to win the lotto. For many women writers and writers of Italian descent, getting published in the mainstream was difficult. To this day some of my favorite contemporary writers, like Sardinian Lina Unali, author of Somali Queen Somali King, can’t get her book republished or reprinted. Lucia Chiavola Birnbaum an outstanding scholar and writer also relied on small feminist presses for her works to come out. With the recent emergence of many small presses, opportunities are improving, but the age of the great editors like Max Perkins who worked with literary writers seems to be over. I was fortunate to have my play The Venus Sanctuary and other works published by Mago Press, both on the web and in hard copy, thanks to Helen Hwang Ph.D., a Korean scholar who has gathered hundreds of women writers and scholars on Facebook and on the website Mago, to share, explore and publish their works as well as Legas Press and the now-defunct Paradiso Press.

L’Idea Magazine: Your first book, “In the Eye of Balance,” won many praises and it turned into a traveling performance. Could you tell us about it?

Louisa Calio: This collection of poetry in many ways traces my “initiation” in the most ancient and traditional sense into a more conscious understanding of myself as a woman, an artist, and an individual with a strong interest and love for foreign cultures and world affairs. The “Isis” theme in this collection is not chosen for pure literary allusion but rather emerged from my personal search to understand my girlhood dreams and hopes for a double/a mate; as well as my repeated thoughts and visions of desert landscapes, Egyptian scenes, and island seas. In learning to understand and accept my love for African and Indian culture, despite the difficulties this sometimes caused me, I found books to be a key to comprehending these personal questions in a larger context.

In my youth, I idealized the power of the intellect and believed all the serious questions could be resolved through education. Yet, I was repeatedly disappointed to meet very scholarly and well-educated people who remained ignorant at the core: racist, intolerant, and unenlightened. Education was not enough to penetrate the deeper layers, and only after years of struggle and despair, did I find a glimmer that life was indeed changing for the better, but not in the progression I had expected and hoped for. Patterns seemed a better way to describe the means of discerning the changes in my life and the world I saw around us. A subtle, more elusive order that we affected and reflected was there. This level I found was more readily tapped through mediation and dance and better articulated in African and Indian culture as well as abstract physics and mathematics. I studied Jung, Tantra, Taoism, and most deeply, the Dogon, whose cosmology seemed to clearly reflect the means and purpose of human evolution and a process of unifying the oppositions we lived in. As the ancients saw, we are the microcosm of this macrocosm; and if we do not change ourselves and our most personal relationships, we cannot change what is outside of us in a lasting and desirable way.

The poems about women celebrate and critically probe this driving feminine force that was often feared by those who did not understand it. The women are real and in my life. Their search for love has sometimes nearly destroyed them, but as we all learn to understand and handle this power, we will (as the Dogon say) be the force that brings about a better world.

Isis II

(For My Beloved & Ogotemmeli)

I come as Isis

Again, again, again, …

Up from pyramidal smoke

That rises

From distant fires

That once lit my shrine

Where I was worshipped

In ancient Egyptian enigmas

Far and wide;

I was loved in Greece

Adored in Sicily

For my words, words, words

Words of Power!

Healing words

Ancient herbal words

That save men and restore them to life.

I took the sun’s very eye

To make myself goddess

To rebuild humanity to lead it to sanity.

I walked across all the great waters of every Nile

For I am bold, bold as love.

I speak words made of flesh…

L’Idea Magazine: In 1985, you had another project of this kind, “Sacred Rites.” What was it about? What does it mean to you to be a performance artist?

Louisa Calio: “Sacred Rites” was a chapbook and performances with the intention of renewing the stagnant images women carried in their psyche and the materialism consuming our western society. Rather than identify with the fallen Eve, the sinner, a woman could now be “An Amazon Goddess Warrior” who speaks from an inner, true power derived from love and knowledge. The poems revealed some of the mystical body and symbols associated with renewal in ancient civilizations.

As a ritual act, the poems are meant to ground our ideas in sound, in movement, and energy, literally connecting us with the living earth. What comes through us can move and affect the world in a healing way. I did this production with friend Cheri Miller and her Tapestry Dance Co.

When the old ones, the shamans, and the village people performed sacred rites and the old mothers in Sicily and Italy said their prayers and novenas for their loved ones, this wasn’t entertainment. Entertainment is wonderful and uplifts us, but to create sacred space, a space that allows in spirit and growth for uplifting and improving the world for the better. Women and vulnerable others have been deeply wounded over 2000 years of patriarchy. Self-healing and development are central to our evolution, both personally and for our planet. Here we are whirling in the new world. I saw something very similar at the amphitheater in Sicily just a few years ago. The word being made flesh as in total theater is the best way I can describe the intention of Sacred Rite as performance.

“Signifiyin Woman”, the poem that won first prize in Canicatti, Sicily in 2017, Il Parnasso International Competition Angelo Vecchio, not only was a deep honor and reconnection with my Sicilian ancestry, it was perhaps the best expression of who I felt I was and am.

“Signifyin Woman: an Italian American Jazz Poem”

Rumor has it she was born a gypsy on the streets of Palermo, Sicily

Then again, some say it was on the bay of Naples

While others claim she was made in New Orleans

under one of those giant trees

with roots that go down so deep

they reach into the earth’s center. Trees with arms

so long, high and wide, they come out and grab you

like the Great Mama.

The dark bark betrays our true origins.

Straight from the core she‘s come

with silvery lips, wide hips, menstrual blood and Oracular Vision.

Part witch and bewitching,

she refuses to be from one place or one race.

SHE travels… in any skins, many skins,

spotted like the leopard, black as the panther

white as the milk in her mama’s rosy-red breasts.

She is red tongues licking fire

a bold soul, an old soul

backyard worshipper and gypsy wanderer.

Sicilian queen,

a dew’s drop on mint green

pure, liquid, mercury,

the sharp in turns,

the quick in glances,

a grain of sand in the Sahara

& between cracks of concrete.

She is the wave length Green, a fish-bellied, crab-crawling, moon-child

secret reptile, Virgin &Mean…the final curtain

the call before the Great Silencing….a Global-eye, spy

the rhythm and the drum-beat of eternity

the curse of blessedness

all female feminine woman

Madonna- puttana, the funneling that germinates

Seeeeedzzzz.

The veiling revealed!

unsettling, rumbling, pulsating speech

earthquaking, rumbling and shaking like she do

when she walks and sways her hips.

YOU got to admit she is Bee-loved

by everything and everyone.

Life’ssssssssssssss

final, exhausting, suffering moment,

when the word is made flesh.

I hate to admit it, but I’m one of her devotees

this Evocateur of Haitian lore

a day’s last ray of sun,

the light, a fright, forbidden fruit, Jew and jewel,

A pure love that instructs, rising from the cavity of womb,

instinctual patterning, dancer prototype, woman

goddess- be damned and man-made manifest …sting……

Earthworm creeper, digger of holes, deeper

The Holiest One, collector of insects and pets

the source of intrigue, the rage in rivers

and all that flows…

is Oh, soooo BEAUTY –Filled

an instrument of divine…

“mercy, mercy, mercy /me /

mus i cal gal, pal

Louis Prima’s sista

signifying woman!

Louisa Calio: Brooklyn and New York City as well as our migration to the suburbs of Long Island did split up our tribe. Yet indelible imprints remained: a deep appreciation of nature, love of our roots, the arts, and a longing for community. Being able to travel to Manhattan to study dance and enjoy theater, music, and museums also had an influence. It was my family again who would bring me to Jamaica. In the 1960s, my Uncle and Aunt left their home on Staten Island to resettle in Montego Bay after tragically losing their son in a car accident. Uncle Val and Christina LoBianco were Sicilian. They fell in love island’s beauty and so did I. An idyllic setting for restoring one’s natural rhythms and health, it was also an excellent opportunity for business. My Uncle opened a garment factory and eventually bought out Ruth Claridge, an outlet of fine women’s wear that later made hotel uniforms and ceramics. They welcomed my family and I to their newfound home in Great River, overlooking the sea, which felt a lot closer to our roots in the Mediterranean than New York ever had.

I had always been drawn to places of great light, perhaps as a result of the many stories I heard my Grandparents tell about the beauty of moonlight on the Bay of Naples and the sunlit fragrant gardens of Sicily which I visited recently. My bones ached for warmth and light, something New England’s long winters did not provide. When I first arrived in the late ’60s, I felt at home at once and found a source of inspiration. Here was the light I had longed for, a light that filled one’s spirit. Philosophers say that the Soul dwells in light, and this environ was the closest expression of my soul I’d discovered with the exception of Sicily and Africa. After living in an era that seems to be suffering from a type of soul loss, in the hurried pace of a high-tech world, computers, tv, fast foods, and lanes, I discovered that Jamaica’s sunshine, clear skies, turquoise sea, an incredible variety of intense color and varied lush landscape, made it easy for me to get in touch with my deeper nature, the poet within me. Each return to Montego Bay became my re-member-ing or the coming together of lost parts of myself within the greater whole. Jamaica’s generous bounty filled me with a rush of exquisite color at every turn, blossoms, scented-flowers, greenery, hillsides, ocean vistas, rivers, waterfalls, lagoon views, mountains almost as high as those in Ethiopia, and a fertile garden of exotic fruit trees, plants, herbs and vegetables that all seemed to call, “Come and walk with me, get to know your true nature that you may treasure it and keep it sacred.” Surrounded by water and sunlight’s shifting play, I need only awaken and look outside at the beauty of the dawn to remember who I was. Here, my writing flourished and my creativity overflowed. This may also account for the many fine artists, painters, and sculptors who are Jamaicans. I wrote poems and stories to express what happened each time I visited and experienced an expanded awareness without any effort on my part. Over time my work would include photos which I have exhibited in “A Passion for Jamaica” at Round Hill Resort and Villas.

L’Idea Magazine: You traveled a lot. Where exactly? What did you acquire from these experiences and how do they contrast with each other?

Louisa Calio: I have traveled throughout Europe, to Sicily, Italy, Norway, Denmark, Spain, France, Belgium, England, Germany, East and West Africa, and through my yoga practice, India. Culture is a delicious prism from which and through which we explore ourselves and others. This is different from reading about a place. We are moved in a way that is palpable, physical, living and at times it touches on what is larger within us. If I was Indian, I would say it awakens our past lives, those strands alive in us that call us to like or dislike a place almost instantly. This may explain why we certain affinities beyond reason. When I traveled to Europe, I felt a balance that existed there. The passionate countries like Italy and Spain evoked a sense of creative energy and chaos, and they were balanced by the more rigid and orderly lands of Germany and England. France seemed familiar and Paris like home. Each has gifts and challenges and when experienced together gives one a greater sense of their own wholeness within the many parts. Culture is not who we are, but more like the clothes we wear. Some we try on for a while and quickly discard, others we explore longer and some we adopt. Travel enables us to see with fresh eyes, keep the spirit of adventure alive and compare and contrast our many aspects both within and outside. Sometimes we find a perfect fit and feel at home as I did with Jamaica and Eritrea.

Henry Louis Gates, Jr. demonstrates in Finding Your Roots, we are more connected than we realize. So too are we becoming whatever if we believe we are not. My poem “Foreign Affairs” was inspired by the realization, that our oppositions are linked more than we can know on the surface. Like many of my poems, this is a long one. I will just excerpt a few stanzas.

Foreign Affairs

In our differences we are made more alike

Your jungles are so like mine

From a common sea

We come we meet we find

Doubles ironies abound

You-exile

Me-child of exiles

Meet on this strange and impure shore

Home of captives-slaves-outcasts and braves

A place of mixings….

Here we are

You who I was taught was different and the dark

Are and are not

But more like me I find in you

Than many who share appearances.

Exchanging gifts

We make new kinds of nourishment

The source of trade-moving the world together

Giving and taking-taking and giving

We make a pact-poet and politician

The labor of generations

Brings us to this spot

“As cultivation spreads impurity recedes.” (Ogotemmeli) Dogon Elder

Louisa Calio: When one is awakened by a soul call, we may find ourselves going to faraway places, and in my case, making a second journey to Africa. My first journey with Educators to Africa took me to the West and Ghana where I stayed with a family and was initiated by two women. My journey to Sudan in 1978 was essential. At the time, I had no idea my Sicilian Aunt, Mariann Calio, had made a similar journey to Libya at the same age (29 years old) or how close Sicily was to Africa historically, as well as geographically. My father’s sister went to visit hers and a part of our family who lived in Libya, then called Tripoli in 1929. They had worked as translators for the Italian government and for the Bank of Sicily in Libya. I learned many Sicilians were also sent to Eritrea in the late 1870s as cheap labor after Italian Unification. These laborers would help develop the railways of Eritrea and eventually help to build Asmara, its famed capital, which looks like an Italian city, Palermo, which has a boulevard named for Asmara, the capital of Eritrea.

“I had come to the place of the long view of history,” where one seeks to better know herself and the causes of her story. I was immediately made more aware of my feminine struggle and its sources on arrival in Khartoum. The sense that women are not seen as fully human, becomes quite palpable in a place where women were chaperoned wherever they went and would later be forced back into being covered from head to toe, to be made invisible both figuratively and literally.

Journey to the Heart Waters is divided into three sections: Part1, Poems of The Arrival: Khartoum 1978 when I am almost barred from entering and possibly worse, by immigration, Part 2, the memory of what inspired the journey, and Part 3, the actual journey which involved stopping over in London where I was guided and prepared for the trip by 3 women mystics.

The experiences in Sudan would open me to a higher vision, beyond the confinements of ordinary time and limiting duality. Each poem exists within this narrative context. Several like “Sky Openings” and “Bhari” have won awards in Sicily. The call to East Africa began unconsciously in my youth with childhood images of the great eye of Horus and dreams of the desert. The trip was inspired by matters of heart, a profound alchemical passion that would evoke what Jung refers to as matters of soul proportion, where the seemingly impossible splits that come with conflicting opposites, seek reconciliation. With love, also came loss and separation, introspection, and finally clear guidance and understanding.

In Sudan, prompted by these highly charged environs: the desert, the blue and white Niles, the cultures of Nubia and Eritrea, I would recognize the archetypal nature of my trip and its ties to Sicily, the land of my paternal ancestors. Going to Sudan also brought me face to face with many families seeking a better life as mine had, and a need to escape from refugee camps, the horrors of war, the pain of separation and the confusion of cultural clashes which I carried in my own DNA. This book is a poetic expression of these experiences.

As author, historian Stanislao Pugliese puts it: “Louisa Calio’s Journey to the Heart Waters is a searing personal work of eternal return and transformation. Calio sets out on a quest that unites southern Italy and east Africa through the image and bodies of the black madonnas who encourage her to seek, to question, to love, to grieve, to revel, and to dance. These poems are a profoundly poignant and well-earned liberation from all that is oppressive in the modern world.”

Bhari- the meeting place of the Blue and white Niles

I stand beside the ancient waters, Nile waters

in the old kingdoms of Nubia, Auxum and Kush

an American woman artist wandering

in distant regions far from my home.Why do I roam?

Is it only to seek a lover from another culture

or is there a greater mystery at work

a modern-day miracle play, a tribal genesis I am to follow

a labyrinth-like route to my ancient, ancestral roots?It wasn’t as easy as was thought to transform

in one brush stroke an Italian to an American.

I had to return to the deeper roots of origin

before Rome or Greece.I have come to the place of the long view of history

a well crossed route, the Sahara,

witness to many civilizations’ comings and goings,

a twilight land where edges blur

into vast sacred emptiness.Land helps give shape to us.

A desert cannot be owned or possessed

in this respect she is closest to our essence.There are many unanswered questions

in the north of Sudan, a desert land

cut by two lines

One blue and tame

One white and wild

Cool are the waters of the two Niles

blending to one

as two lovers might.

L’Idea Magazine: But you are also a photographer…

Louisa Calio: Living in Montego Bay, Jamaica, presented me with a different approach to sharing my work since I lived far from Kingston, the intellectual hub of the island. I was fortunate to have been asked by Josef Forstmayr Managing Director of Round Hill Hotel and Villas to arrange an exhibition. I began with “A Passion for Africa” using my photos from my journey to Sudan and often blending the images with poems. Later on, I did “Passion for Jamaica I & II.” I met a Jamaican photographer Robin Farquharson who also knew my mentor, Robert F. Thompson; we began putting together our Passion for Africa and then Passion for Jamaica. I also had a friend Ann DeLisser who went on many safaris to Tanzania and she joined us and her safari guide Sean Lues who actually sent his images from Tanzania for the exhibition. A Jamaican visual artist, Cecil Ward who also done a series of drawings inspired by Lamu joined. I read poems and we had African music play all throughout the event.

Previously I had shown my photos with the Arts league in Mo Bay and in Florida, but this allowed me to invite other artists, curate, and read. For “Passion for Jamaica”, my husband who is also a photographer added his amazing photos of the ’50s-’70s of Jamaica to Robin’s work. We had a live mento band to create a more total experience with my poetry. Skip (Henry Louis Gates, Jr.) my old friend happened to be there and helped open the show for me. It doesn’t get much better than that and talk show host David Gregory who was staying at Round Hill bought several of our photos. I have merged some of the photos with poems in a series I hope will one day be a coffee table book. The vistas on this island, nature, brimming with beauty, color, and life, as Jamaica’s people continue to inspire.

As I said, on my journey, grounding or sharing in a physical way, not only by intellect alone took on great significance over time. I had learned more of traditions like those of Native Americans and the villagers of Sicily and Italy that took the word and made it flesh by actions in the community for the sake of the greater good and healing purposes. They did so in rituals that acknowledged the relationship of what is above, in between and below. At the time, I had come out of the spell of my history and the story of Eve, the woman as the sin maker and discovered a more ancient feminine upon which I could rebuild myself or “Make Myself, Make Myself/ Shedding the yoke of Centuries, she begins anew” the voice of Isis said in my poems and she was the new “Rites of Isis” At the same time I was meeting visual and theater artists and musicians to collaborate with. I got a grant from ECA in New Haven to do the stage production of “In the Eye of Balance” which was a dream come true.

L’Idea Magazine: You taught English and Creative Writing for a while. What made you stop and channel yourself back into the Arts?

Louisa Calio: Being in a classroom full time, felt too confining. I love being outdoors and free to meet people from all walks of life and backgrounds, to follow my heart, my call, wherever it took me. The arts and my explorations in consciousness took me to California to work with Brugh Joy MD, an incredible physician turned mystic, in the high desert. I went to Ghana and attended rituals where I was initiated by two Ghanaian women. I went to lectures on African Art and literature at Yale. Traveled to the Niles of Nubia and to my ancestral homeland Italy and Sicily. I was on a quest. Yet, I did keep teaching even while I was involved with City Spirit Artists, Inc. I taught creative writing in jails, senior centers, schools and organized performances whenever possible, especially after I was able to become a consultant rather than a full-time Executive Director, which entailed a lot of fund-raising admin and grant writing.

L’Idea Magazine: Louisa, your teaching experiences seem to be quite numerous. You taught drama and dance. How did that come about? You are also a certified Yoga instructor. Do you teach Yoga too?

Louisa Calio: I liked the way a colleague and friend, Chickie Farella, characterizes herself as an Independent Scholar on a quest of self-discovery. I certainly loved learning and never stopped seeking and inquiry. I shared whatever I could wherever I happened to be at the time. When I graduated from College in Literature, I considered a career in academia, but it was the late 1960’s and I wanted to “change the world.” I thought of joining the peace corps. I had become close friends with several Ethiopian, Eritrean, and Sudanese students at SUNY. We were passionate about making the world a better, more egalitarian place. However, war was looming in the region and they suggested the Peace Corps was not a good idea. Instead, I took a job teaching at a State Mental Hospital and then landed a full-time position in Philadelphia, where I was hired because of my participation in a program at SUNY called The Institute for problems dealing with Desegregation. I was in the first programs in African American Studies with scholars like John Reilly who introduced me to Jean Toomer, Richard Wright, Ralph Ellison, James Baldwin, Langston Hughes, etc. and I loved their work. Jean Toomer, a mystic who lived in many skins, would influence my own path and confidence in it. I still own a copy of the then-unpublished manuscript Essentials, which spoke in a language of the soul, a visionary language poet writes in. His book Cane was dog eared from my readings of it.

In Philadelphia, where I taught in the early 1970s, we had The Scholastic Black Literature Series as tools. I had a chance to introduce Langston Hughes, Sterling Brown, Gwendolyn Brooks, etc. wonderful black writers to my students for a few years, until all this was dropped and the old curriculum forced back in. The race wars continue. Teaching there at the time was dangerous. Gang wars in West and South Philly never stopped. I took classes in Temple about the Philadelphia gangs and learned I was living in a war zone. One of my best students was shot and another fatally stabbed. After five years, I needed to move away and regroup. When I did, I realized all those pieces of paper with poems scribbled on them was where I longed to be. So, In New Haven, after being an arts administrator and auditing classes at Yale, I began doing performances of my own work, I found the artist within, and “I loved her fiercely.” I again had a chance to earn another degree and was asked to apply to American Studies at Yale, but that would mean giving up my flexibility and freedom. I would not be writing my own work but writing about others. At the same time, I was drawn to practice yoga, meditation, and a continue with soul guides, Brugh Joy and Robert A. Monroe who offered retreats designed to help open one to numinous experiences that break down the walls of ego and the more limited self. I decided to attend and began a 20-year journey with this work and the poems you have seen flowed and continue to flow when I get in touch with this Self.

Another essential realization came, which was, in order to do this work, I needed a grounded and healthy body. While I swam and did dance to keep fit, yoga offered me a connection with body, mind, and spirit. I had what mystics describe as a kundalini experience in 1975, which changed me in ways I have done my best to write about and express. Books guided me to and through it. One such book was Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras; it changed my life. After this experience, I was given a hatha yoga book written by Swami Vishnudevanada. I began to do yoga from it and would eventually do my teacher training at his ashram in the Laurentian mountains. I returned to Jamaica. In Montego Bay, I taught yoga, meditation, and did the types of workshops I had been flying all over to attend. I again wanted to share it all with the world. The 1980s offered me a chance to go back and forth to New Haven and Jamaica a wonderful balance for a writer.

L’Idea Magazine: You founded and were for quite a few years the Executive Director of “City Spirits Arts Inc,” a non-profit arts organization. What was the trigger for doing so and what is City Spirits about?

Louisa Calio: City Spirit Artists began as a Bicentennial project of the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) in 1976. I was hired to coordinate a grant awarded to New Haven, Connecticut—one of 76 cities chosen by President Jimmy Carter, to celebrate our nation’s birthday—by bringing the arts and the community together in a variety of ways. I was in a major life transition at the time, after 5 years of teaching English and Dance in the Philadelphia inner-city schools, involved with urban outreach in the arts there, while getting a Masters degree at night at Temple I moved to New Haven, Ct. for personal reasons, where I would start my life over. Writing became my major commitment. Living near Yale allowed me to sit in on classes offered by Robert Thompson, Professor of African Art and religion, and build friendships with exciting scholars like Henry Louisa Gates, Jerry Ward, Robert Stepto, etc. I needed to look for work again and my housemate Terry Lennox, a painting student at Yale Graduate School and future collaborator opened up the newspaper and said, “look this job sounds like you!” The job description fit my patchwork life with my journeys to West Africa, work in the arts, teaching, creative, and community commitments all in one. The competition was fierce. I was interviewed by 13 people from all walks of life, social workers, arts affiliates, lawyers, teachers, never expecting to get the job. But I was born on the 4th of July and seemed to feel at home among the committee who did finally hire me.

We chose to do several events, as well as arts programs in halfway houses, women’s shelters, senior centers, jails, and schools. The program was so successful that the original board decided we could expand and keep it going. We applied to the NEA (National Endowment for the Arts) which gave us a grant and the New Haven Foundation to continue our budding programs. Then our greatest breakthrough additional funding—thru the city and CETA, (the Comprehensive Employment Training Act). allowing me to hire artists both full and part-time artists to direct and paint murals, offer arts programs of all types to prisoners, Hospice patients, seniors; children, etc.

My career went from coordinator to first Executive Director and founding member the following year. City Spirit Artists Inc. was a story of the struggles artists had and have to sustain funding, keep creating, and trying to make a living. We also had a battle with our initial pass-through organization. Through it all, I was again blessed with two incredible women, our President Elizabeth Kubler, an artist and community activist and dramatist-educator Mary Hunter Wolf now a legend, along with committed board members like Congresswoman Rosa DeLauro, Louise Endel, etc. a few local bankers and lawyers. While it could be daunting to work with all these people, I felt this was worth the effort. To “Discover the Artist in Yourself” our focus, and a more idealistic aim, artist inclusion on the board as decision-makers; that however, was very challenging. We brought artists of all races and ethnicities together with business people to do it all. City Spirit served the greater New Haven community for 25 years! Over those years we hired hundreds of artists to paint hospitals, teach, perform, write, sing, dance, in hundreds of settings, reaching the hearts of thousands. It helped grow my dual career as an artist/poet and administrator.

Many of the people in City Spirit remain in the arts, managing as best as we can, juggling jobs and lives. City Spirit Artists Benefit Dance Concert at Educational Center for the Arts with Willie Ruff, Yale School of music and many performance and visual artists who created the set and shared their gifts.

Louisa Calio: The new feminine rising, nature, both human and planetary, the need for balance, harmony, and compassion both internally and externally. The poems are personal because they come from inner revelation and are also universal because they are tied to current issues of war, gender, societal imbalances, and ultimately the survival of us on our planet. Some are inspired by love and relationship and others by family.

When we are fortunate enough to stop and take stock of our lives, enter the silence of our true being, and rediscover who we really are, the purpose of our earth-walk on this beautiful planet that offers a remarkable opportunity and mirror to the natural wondrous patterns within as well as externally. The poems are a celebration of these realizations that came as a result of my personal journey, inward and outward, beyond my fears and limiting beliefs about myself, the earth, love, and the feminine. The inward journey became a call to heal the splits within myself that the outer world was mirroring, as well as a realization that the outward world also held up a mirror to my intrinsic wholeness. The wonders of the galaxies, the stars, the enchantments of the forest, the powerful currents that flow are also within me. I too am electricity. The poems are designed to express moments of revelation, reflection, ecstasy, and just plain play, that come to us daily when we are open to them.

In recent years, I have been fortunate to have several Italian women scholars interested in my work who have written about it. Prof Elisabetta Marino of University of Rome Tor Vergata and Cinzia Marongiu from the University of Gutenberg Germany. Cinzia, an Italian/Sardinian who presented at an IASA conference in Rome, summed up my intentions beautifully in her paper when she wrote,

“Louisa Calio is eclectic and sometimes difficult to label neatly within one genre; her poetry draws on a vast array of transnational texts and influences, for she never felt part of a monolithic or homogeneous culture, as she recently asserted, “my soul seemed to come from many places and many of them had both a rich history and a history of feminism.” Calio’s work mirrors “a sensitivity to multiculturalism and ethnic diversity that is sometimes lacking in Italian American culture” as Stanislao Pugliese poses it. Certainly, proud of her Italian American roots, Louisa Calio situates herself within a wider literary tradition. Her works can be associated with what Estrella Lauter sees as a widespread revision by women artists of “key elements of Western mythology,” especially as they concern women’s relation to nature (172). With reference to the work of Susan Griffin, Marge Piercy, and Audre Lorde, among others, Lauter finds “a degree of identification with nature, without fear and without loss of consciousness” which occurs in the works of “surprising number of women.” “Cassandra’s Visions” a visionary poem over 100 lines and 20 stanzas sees the future as a choice and one where contemporary problems and ecological issues are to be faced.

“I know the horrors of the wasteland

Yet to come

The feminine spoken of

I thought I was bound to them.

Yet, the Sybil Cassandra doesn’t see only doom. She invites with hope

“To see you

To see you clearly

I see you at the crossroads…

We may become scorched earth

If you deny the forces of water…

The sources of moisture…Come Eat My Roses

Dive into the face of love

Touch the blood of passion as it drips from the cup.”

She, however, reminds us we are the story and we can through love change the outcome.

L’Idea Magazine: Your work has been translated into Korean, Russian, Italian, Sicilian, and Tigrinya. I can easily understand Italian, and maybe Sicilian, but what about these other languages. What prompted an interest in your writing in the countries where these languages are spoken?

Louisa Calio: Some of these translations as a result of my readings for Arba Sicula, an organization dedicated to the study and preservation of Sicilian language and Culture, where I currently serve on the advisory board and well as Cross Cultural Communications, a press established by poet Stanley H. Barkan, 50 years ago, that brings writers and translators together. My friendship with poets and writers in Europe, our common themes and concerns, and participation in international competitions, have expanded the opportunity to have my work translated. After the poem “Sky Openings” won words of gold in Sicily, poet Marina Akmadova asked if she could translate it into Russian. I was deeply honored. Meeting gifted translators like Elisabetta Marino and Nino Provenzano, gave me the chance to reach others, Italians and Sicilians, as well as Koreans, Russians, and author Amanuel Sahel known widely in the Eritrean community, have translated some of my poems. Elisabetta Marino has translated many and we hope to do a bi-lingual edition of my book once we find a willing publisher.

Angie’s hands have Seasoning (inspired by my maternal Grandmother, Angelina Consolmagno)

Angie’s hands have seasoning

the neighbors and relatives would say

when they got to partake in one of her home-made meals.

Her hands would go through each tomato or vegetable

sorting the good from the bad

the freshly picked garden varieties

delicately, as though she was touching a bit of eternity

or the cosmic web lined with ancient secrets.

She could sense the life force in the greens or reds

the messages of love carried from the ancestors

which seemed mirrored in her warn and well worn hands.Without any ego driven desire

she took her medium of expression

and laid it out perfectly on the table

like an artist preparing her tools

for an object of great beauty.

She worked with focus and intention

to shape her creation.

Then before cooking the ingredients of any dish

whether a complex pastry, homemade ravioli

or a simple soup she mixed,

Angie placed her hands a few inches

above the contents

the way a healer does

when he scans the human energy field

and moved them around

not like a magician to distract the viewer

but with tenderness, sensitivity,

an awareness of the mysteryShe knew the greatness within the small

the secrets of how to nourish us all

with what she created through nature

and those well seasoned hands.Italian Translation by Elisabetta Marino

Le mani di Angie davano sapore

(per mia nonna Angelina Consolmagno Marchesani)Le mani di Angie danno sapore

dicevano vicini e parenti

quando partecipavano a uno dei suoi pranzi fatti in casa.

Le mani passavano in rassegna ogni pomodoro o verdura

separando i buoni dai cattivi

le varietà dell’orto, appena colte,

con delicatezza, come se stesse toccando un granello d’eternità

o l’intreccio del cosmo, orlato di segreti antichi.

sapeva percepire l’energia vitale negli ortaggi verdi e in quelli rossi

i messaggi d’amore dei predecessori

che sembravano riflessi nelle sue mani calde e consumate.Senza desiderio alcuno di farsi notare

prendeva il suo mezzo d’espression

e lo disponeva, impeccabile, sul tavolo

come un artista che prepara i suoi strumenti

per realizzare un oggetto di grande bellezza.

Lavorava concentrata e attenta

per dare forma alla sua creazione.

Poi, prima di mischiare gli ingredienti di qualsiasi piatto

sia che fosse un dolce elaborato, ravioli fatti in casa

o una semplice zuppa,

Angie vi poneva sopra le sue mani,

a qualche centimetro,

come un guaritore

quando scruta il campo d’energia nell’uomo

e le muoveva

non come fa il mago, per distrarre l’attenzione

di chi guarda, ma con dolcezza, sensibilità,

e consapevolezza del mistero.Conosceva la grandezza in ciò che è piccolo

i segreti di come nutrirci tutti

con quello che creava attraverso la natura

e quel sapore dalle sue mani antiche.

L’Idea Magazine: You were also the Director of the “Poets and Writers Piazza for Hofstra’s Italian Experience.” What did that entail?

Louisa Calio: This was a labor of love and came after an accidental discovery of an organization called AIHA now IASA created by Italian American scholars, who, like Dean Anthony J. Tamburri and Fred L. Gardaphe offered a conference in Ohio called Shades of Black and White, Africa Italy and the USA in 1997. I felt I finally came home and found an inclusive community of Italian American writers who could speak my inclusive language. At that first conference, I met Dr. Lucia Chiavola Birnbaum, Chickie Farella, Mary Beth Moser, Elisabetta Marino and Lina Unali, women I would befriend and collaborate with to this day. I had been part of a loose feminist and African American community of writers who offered me a better understanding of where my work emerged from, but here it was the Italian American diaspora of writers and scholars who offered that mirrored the work, inclusive of former African colonies as well as Sicily, Malta and Sardinia. We were all affected by our American Identity too. I attended many conferences and met exciting authors like Marisa Labozetta, Karen Tintori, Paola Corso, etc. who I wrote about and who wrote about me or invited me to submit.

At one conference, I met an Italian American radio show host who wanted to interview me; he mentioned that Hofstra had an annual Italian Festival, but had never included literature. In 2000 Vito and Carolyn DeSimone with the help of Robert Spiotto helped us organize the first poet’s piazza. Frank Ingrasciotta, a gifted Sicilian American playwright performed sketches from his one may play: Blood Type Ragu. It was brilliant. For the next twelve years, I invited writers to this annual event learning of a broader community of them through Professor Robert Viscusi of Brooklyn College then-president IAWA and Gaetano Cipolla President of Arba Sicula. A host of authors, Nino Provenzano, Michael Palma, Peter Covino, Maria Gillian, Maria Fama, etc very fine writers gathered annually and shared their work. I did their bios, samples of their work and put the event together with my Jamaican husband without whose help both my career and this event could not have progressed. Not only did he do the setup and photograph the event, but he also continues to help in my itinerant life as poet, performer and photographer contributing his amazing photos of Jamaican life. After each reading, we would gather Italian style to break bread, dine, and drink wine. Eventually, we included Sicilian singers, a Calabrian musician Dom Enico who played goat skins beautifully, and the larger Italian American Community. Professor of History at Hofstra and author Stanislao Pugliese was a delight to work with. He invited me, along with two outstanding Eritrean scholars, Tesfatsion Medhanie, and publisher Kassahun Checole to present my book Journey to the Heart Waters within the context of Italian colonialism, a much under-discussed topic that I hope will be further explored by Italian, Italian American and African scholars together.

L’Idea Magazine: Are you working on any new projects at this time?

Louisa Calio: Oh yes, I have several: a collection of poems and essays with photos tentatively entitled: A Passion for Jamaica which is nearly finished; a collection of poetry and stories about family and other journeys called, Brooklyn and Other Migrations, and the Hope for the publication of my novel, Lucia Means Light, an Italian American woman’s journey to consciousness.

L’Idea Magazine: Any particular dream that you long for to be fulfilled?

Louisa Calio: Yes. To see all my writings published before I die and the publication of my novel by a mainstream publisher & then to have it become an Oprah Pick. I have made several dream boards with that in mind. I would love to have one of those pajama parties Oprah arranged for authors in the beginning of her commitment to literature and soul work. I even wrote her an imaginary letter with that hope. She has done so much for writers, especially women writers and writers who talk about our soul.

L’Idea Magazine: If you could meet a person from any historical period and ask them questions, who would that person be and what would you ask them? Several

Louisa Calio: My initial response is the following list: Anais Nin, Virginia Woolf, Sylvia Plath, Socrates, Rilke, Dante, James Merrill, Coleridge, Paramahansa Yogananda, Patanjali, and Rumi. If I had to choose one, which would be very difficult, I guess it would be the Sufi poet Jalāl ad-Dīn Rumi with the hope of learning about his path to enlightenment and amazing ability to express his ecstatic experiences in a language of love and poetry.

L’Idea Magazine: A message for our readers?

Louisa Calio: I want to begin by thanking my readers and the scholars especially those who write to me and about me as well as all readers of literature. You make this possible. I have been so moved by your presence at my readings and the time you take to respond to the work. Last year when Idea Boston happened at the Dante Center thanks to the wonderful Nicola Oricha and I AM BOOKS of Boston, I presented my book, and a young woman appeared. She told me how she read all my work and followed me on Facebook and found my work an inspiration and how that helped her gain confidence in her dreams. I was truly moved.

Learn to listen to and follow your heart, develop the tools that enable you to know what your heart says as compared to your habits, intellect and outside influences. Don’t be afraid to dream and seek your own path. You are a unique individual as well as part of a community and ultimately part of our whole planet that so needs your efforts to balance now. Many thanks to you for this opportunity.