by Laura Klinkon

As a student in a college poetry class I had asked myself and written a poem reflecting a certain desperation as to how to approach a poem. It went like this:

One Way to Read a Poem

Zero in

Close

Bend

The right brow

Over the right corner

The other over the left

Grip

The lower right

With the right jaw

The left with

The left now

Inhale.

It was, of course, facetious, but, even now, I don’t know if I have as yet, really solved the problem. One probable reason is that there are many different kinds of poems, but another is that reading poems is not the same as reading other types of literature. Even the desire to read poetry is different.

In our day and age, one’s choice of reading matter often depends on how easily and speedily satisfaction may be had from it. Recently I heard in a video talk a thoroughly cultivated man, confessing that he especially likes short stories, because he can finish reading one or two in the midst of his being involved in some other activity. And since short stories, to be successful, need to capture the reader’s attention quickly and continue chronologically, they also tend to be relatively easy to follow. In addition, a short story is complete in itself, whereas a poem often requires or invites several readings.

As for the novel, since the novelist needs to set the stage for often complicated events to come he or she may take longer to capture the reader’s attention, but the reader actually expects to sit down to a more relaxed, extended experience. The novelist, moreover, accompanies the reader gradually through the intricacies of his story; unlike the poet who more often than not depends on the reader to guess, intuit, or unravel his or her meaning or intent.

One is tempted to call attention to “entertainment value” as a criterion for one’s choice of reading matter, but the definition of ‘entertainment” can vary from reader to reader, from genre to genre, and from one work of literature to another. An article or essay, for example, may be more straightforward in its objectives; it is expected mainly to inform or to explain a point of view, yet, it is more casually chosen as reading material, because not only is it shorter than a full-length treatise, but its content is more given to a desultory reading. To be read mainly for information or perspective, its sub-topics are most likely flagged in each paragraph, so that parts less relevant to the reader may be skipped. In poetry, skipping is likely fatal to an adequate understanding or appreciation.

Within the poetic genre, there is a great variety of content, form, and appeal, and while the decision to read may depend on all of these aspects, it may simply have to do with the reader’s familiarity with or curiosity about the author. Moreover, it would seem that especially in modern times, poetry has become so personal that reading it is not so much a matter of entertainment, as it is of connection. That is to say that, as a reader, you are likely to prefer a poet and/or a poem you can relate to, while its aesthetic or entertainment appeal simply makes re-reading more likely.

In this day of instant email correspondence and personal video exchanges that are conveniently scheduled, ease of access along with speed of understanding and relatability, become important values. For this reason I am attempting here, to formulate a way to approach poems that might be read without the frustration that may attend an initial foray.

My approach is by no means revolutionary; it merely intends to open a window to reading poems and lead to a fuller understanding and enjoyment of the work of art. Poems, for the most part, are not something you can grab and run with or from; rather they have to be savored on their own terms, if they are in any way to become friends.

My premise is that there are six elements in every poem that could be fairly quickly identified just to “get into it.” You are probably aware of all of them, but, to identify them quickly for each poem, takes practice. The first three are related enough that they may be encapsulated in a single sentence. The three elements are: The Speaker, The Listener, and what the Speaker Intends to Say.

Usually, the Speaker can be ascertained from the first few lines of a poem, while the Listener and Intent may be initially guessed at by the Speaker’s tone.

Here is the first quatrain of Shakespeare’s Sonnet 73, for example:

That time of year thou mayest in me behold

When yellow leaves or none or few do hang

Upon those boughs which shake against the cold,

Bare ruined choirs where late the sweet birds sang.

Obviously, The Speaker, who is comparing himself to late autumn, is an elderly man. The Listener, directly addressed as “thou,” could be identified, due to this pronoun, as a friend based on Elizabethan usage. Nevertheless, the fact that the Speaker is sharing personal observations about himself, also indicates that the Listener is a friend. Our preliminary sentence then might be: The elderly man observes to his friend some feelings about his old age. (A more precise statement may be formulated as the poem proceeds.)

Most often neither the Speaker nor the Listener are precisely identified, but the reader should expect to be given strong clues. The Speaker, also, may not be the poet him or herself but rather, a persona or a character part that the poet assumes. Take, for example, the dramatic first lines of the Fatal Interview “Sonnet XXIV” by Edna St. Vincent Millay*:

Whereas at morning in a Jeweled Crown

I bit my fingers and was hard to please,

Because Millay is a poet writing in the 1920’s, we can guess from these lines that the Speaker is a persona of royal blood, who, as indicated by nail biting, has a nervous or capricious personality. Since the Speaker does not address anyone directly, we can guess that the Listener, because she is speaking of personal feelings, is, as in Shakespeare’s sonnet, a close friend or it could simply be that the “princess” is talking to herself or to the reader as a friend.

To determine what the Speaker is wanting to say to the Listener, we will probably have to read to the end of the poem, but we can make a tentative guess from the phrase “Whereas at morning”, that she wants to tell about her day.

Millay’s first quatrain goes on to indicate how her day might have progressed:

Having shook disaster till the fruit fell down

I feel tonight more happy and at ease:

In other words, the “princess” intends to tell how a “disaster” she has caused, has led to her feeling “happy and at ease.”

We have only to read in the next quatrain, to learn what apparently is the “fruit” or the effect of the “disaster:”

Feet running in the corridors, men quick—

Buckling their sword-belts, bumping down the stair,

Challenge, and rattling bridge-chain, and the click

Of hooves on pavement—this will clear the air.

In Shakespeare’s second quatrain,

In me thou see’st the twilight of such day

As after sunset fadeth in the west;

Which by and by black night doth take away,

Death’s second self, that seals up all in rest.

we see that the poem proceeds, not according to the day’s events, but by a series of comparisons to himself: he was, at first, like a tree, he is now like the twilight, and in the third quatrain, he compares himself to a dying fire:

In me thou see’st the glowing of such fire,

That on the ashes of his youth doth lie,

As the deathbed whereon it must expire,

Consumed with that which it was nourished by.

Thus, we see that the progression is by comparison, but also, if we consider a bit more closely, by intensification: a tree in autumn is a relatively mild comparison, a twilight that ends in death-like sleep is more serious, and a burning fire quite tragic.

Millay’s third quatrain, instead, does not intensify, but returns to a quieter atmosphere, with the “princess” alone in her room and resting:

Private this chamber as it has not been

In many a month of muffled hours; almost,

Lulled by the uproar, I could lie serene

And sleep, until all’s won, until all’s lost,

We could say that Millay’s sonnet proceeds by swinging contrasts: private feelings change to harsh military sounds, then, again, to private feelings.

The last couplets of the poems finally make clear what each wanted to say; Shakespeare’s Speaker who has been repeating to his friend all along, “In me thou see’st”, now reveals outright:

This thou perceiv’st, which makes thy love more strong,

To love that well which thou must leave ere long.

Millay’s couplet reveals yet more contrast: once again she leaves the private setting, to emerge into a public one, and again brings to bear extreme contrasts:

And the door’s opened and the issue shown,

And I walk forth Hell’s Mistress—or my own.

In these sonnets we have already seen how the devices of comparison, repetition, and the juxtaposition of contrasts can move a poem forward to its climax or conclusion. We could also point to other devices they share, the sonnet form being the most obvious, with its fourteen lines, its regular rhyme scheme, and iambic pentameter meter; chances are, on closer examination we could find other devices.

Generally speaking, devices are the nuts and bolts of the poem that contribute to its structure and special effects regarding the way the poem is read and heard. Examples are the use of repeated similar sounds such as vowels and consonants, the use of different kinds of diction, formal or slang, contemporary or old-fashioned, vulgar or academic. But there is also the use of allusion or references to historical, mythological, literary, cinematic, or contemporary personalities or events that indirectly offer innuendo to the poem’s meaning. Lewis Turco’s widely used Handbook of Poetics includes a ten-page double-column index in 8 point type that constitutes essentially a list of devices. However, the general reader of poetry need not have at hand the names of all the “tools” a poet uses, but only an interest in discovering the way that poems acquire their meanings and effects.

Most poems, in the meantime, use a limited number of devices, which facilitates to some degree the reader’s understanding and appreciation of the poem’s artistry.

In some listings Imagery is included as a poetic “device,” but Imagery by itself, is in many people’s minds, the life-blood of poetry, in that it drives the sensual impressions it creates. Though imagery in traditional poetry has tended to be more concrete or based on the five senses, in modern poetry other kinds of imagery have been identified, such as, for example, kinetic or procedural or even abstract imagery; in these instances the impression could be seen as more mental.

In Sonnet 73, Shakespeare uses concrete images from nature that leave a visual impression in the reader’s mind, yet its Speaker suggests that the images describe himself. In so doing, he flags the image as a simile or metaphor, which adds something more to the meaning than just the visual impression. In this sonnet, we are presented with a sense of what old age may feel like.

In Millay’s more modern sonnet, the images are visual and auditory, but also allusive and symbolic: the “Jeweled Crown” alludes to and is symbolic of royalty, the ‘biting of nails’ alludes to an anxious state of mind, the tree of “disaster” is symbolic of some shattering event caused by the Speaker, and the images of “sword-belts” and “bridge-chain” allude to medieval warfare. These images bring to mind not only pictures and sounds, but refer to fairy-tale-like events symbolic of a critical stage in the “princess'” life. Dressed in these “costumes,” the impression created sparks the reader’s imagination and draws on his or her experience.

Images are, indeed, the life-blood of poetry, but in modern poetry, the reader may encounter new kinds of images and more complex effects, as in the following two contemporary and subtly humorous examples, which are again sonnets, chosen for the relative brevity and recognizability of this form.

I am going to describe the poems according to the six major elements I’ve suggested, but will leave it up to you the reader to decide if you agree with my description and to think a bit more in terms of how the poems achieve their artistic effect. The first modern sonnet is entitled “Sonnet” by the 2001-03 U.S. Poet Laureate, Billy Collins; the other, “Library Lovers,” is a formally traditional sonnet by Austin MacRae, contemporary poet, musician, and songwriter.

Sonnet by Billy Collins

All we need is fourteen lines, well, thirteen now,

and after this next one just a dozen

to launch a little ship on love’s storm-tossed seas,

then only ten more left like rows of beans.

How easily it goes unless you get Elizabethan

and insist the iambic bongos must be played

and rhymes positioned at the ends of lines,

one for every station of the cross.

But hang on here while we make the turn

into the final six where all will be resolved,

where longing and heartache will find an end,

where Laura will tell Petrarch to put down his pen,

take off those crazy medieval tights,

blow out the lights, and come at last to bed.

Permission by Chris Calhoun Agency, © Billy Collins.

Speaker – Listener – Intention

A writing coach explains to initiates how to write a modern sonnet.

Progression: General to specific pointers:

General length and topic, what is NOT needed, what IS needed.

Devices: Allusion, informal speech. sonnet form

Alludes to sonnet form, length and subject, Elizabethan form, Petrarch and his love

Informal speech: rows of beans, bongos, hang on there, crazy, blow out the lights

Imagery is mostly Situational:

A poetry workshop, poet making choices, lover and poet going to bed.

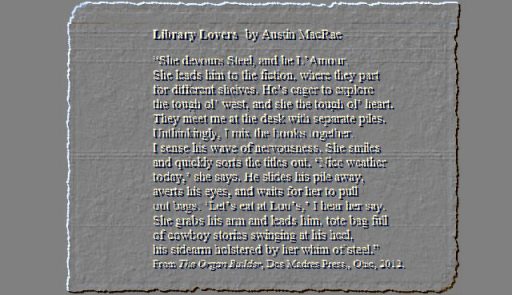

Library Lovers by Austin MacRae

“She devours Steel, and he L’Amour.

She leads him to the fiction, where they part

for different shelves. He’s eager to explore

the tough ol’ west, and she the tough ol’ heart.

They meet me at the desk with separate piles.

Unthinkingly, I mix the books together.

I sense his wave of nervousness. She smiles

and quickly sorts the titles out. ‘Nice weather

today,’ she says. He slides his pile away,

averts his eyes, and waits for her to pull

out bags. ‘Let’s eat at Lou’s,’ I hear her say.

She grabs his arm and leads him, tote bag full

of cowboy stories swinging at his heel,

his sidearm holstered by her whim of steel.”

From The Organ Builder, Dos Madres Press,, Ohio, 2012.

Speaker – Listener – Intention

An observer or librarian tells (the reader) an anecdote about a couple visiting the library.

Progression: dramatic action

Couple enters library, meets at check-out, sorts books. go to lunch, she leading.

Devices: Allusion, dramatic presentation, diction, puns

Alludes to two novelists, western and romance

Dialogue: Nice weather…, Let’s eat at Lou’s

“Cowboy” diction ‘ol west/ol’ heart

Puns: sidearm, holstered

Imagery : Behavioral

Key behaviors: devours, leads, meet, mix, nervousness, smiles, sorts, averts his eyes, grabs

Hopefully, the present approach to reading poems will help readers in seeking out and discovering poems and poets that speak to them, regardless of the variety of voices, paths, and tools they display.

Read also the review (in Italian) of La Lira Silente, Primi Sonetti Di Edna St.Vincent Millay.