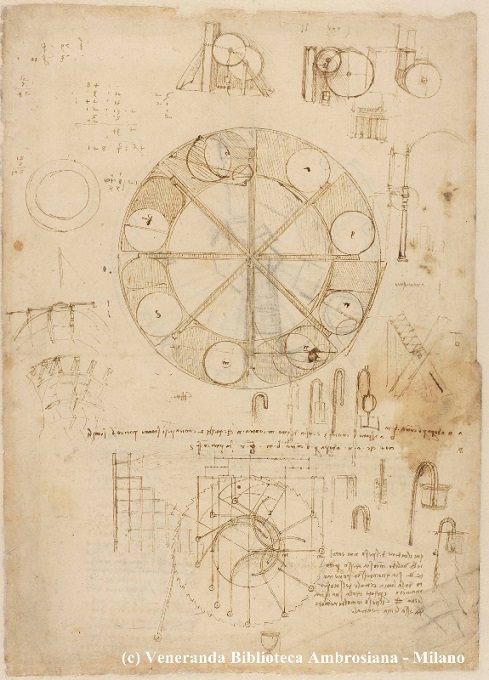

The Codex Atlanticus consists of 1119 sheets and was donated in 1637 to the Biblioteca Ambrosiana, founded by Cardinal Federico Borromeo in 1609 and one of the first public libraries in the world. Basically Leonardo’s entire life as an artist and a scientist appears in this extraordinary collection, which covers a time frame that goes from 1478, when Leonardo was still working in his native Tuscany, to 1519, when he died in France. The folios deal with various subjects ranging from mechanics to hydraulics, from studies and sketches for paintings to mathematics and astronomy, from philosophical meditations to fables, all the way to curious inventions such as parachutes, war machineries and hydraulic pumps.

In his will Leonardo donated his writings to his loyal disciple Francesco Melzi who followed the master to France during the years he spent at the court of King Francis I.

Melzi was very aware of the inestimable value of this legacy and of the the enormous trust that his Master put in him and he jealously kept the folios in his villa in Vaprio D’Adda near Milan, until his death in 1570. Unfortunately, his descendants did not prove equally zealous and let the huge heritage become prey of unscrupulous art dealers.

At the end of the sixteenth century the sculptor Pompeo Leoni managed to retrieve some of Leonardo’s folios from Melzi’s heirs, and set out to mount them onto large sheets, used at the time for making atlases: that’s why the Codex would be named from then on “Atlanticus”. Leoni did not follow a precise ordering criteria though, privileging the overall aesthetic effect of the volume and creating a collection destined more for an admiring audience than for scholars.

The Codex was then sold by one of Leoni’s heirs to Marquis Galeazzo Arconati, who understood its real value and in 1637 decided to donate it to the Biblioteca Ambrosiana, which would be able to ensure the Codex’conservation and transmission to future generations in virtue of its mission, devoted to culture and study.

Such a treasure, however, did not escape to the experts who drafted the list of the works to be transferred to Paris after the conquest of Milan by Napoleon Bonaparte in 1796. For 17 years it was kept in the Louvre Museum and then in 1815, when the Congress of Vienna ratified the return of all artworks stolen by Napoleon to their countries of origin, it was given back to the Ambrosiana, where it is still jealously conserved.

A curious anecdote tells that the commissioner engaged by the Austrian Empire (under which Lombardy fell) to reclaim their artworks was an elderly baron, almost ignorant of science and art. He was about to leave the entire Codex Atlaticus in Paris as he had mistaken it for a manuscript in Chinese, because of the Master’s well-known reversed handwriting. It was Antonio Canova, the commissioner for the Pope, who realized the mistake and firmly asked him to bring the Codex back to the Ambrosiana.

In 1968 the Codex underwent an impressive restoration work at the monastery of Grottaferrata in Lazio, during which it was bound in 12 massive volumes while maintaining the original sequence ofsheets set by Leoni. This choice led to many problems of conservation and study, since in order to make comparative analysis of the folios it was necessary to consult more volumes at once, or to consider drawings placed in very different points of the same tome.

In 2008 the “Collegio dei Dottori” chaired by the Prefect Monsignor Franco Buzzi, in cooperation with the “Cardinale Federico Borromeo Foundation“, decided to solve this serious difficulties and to start anepoch – making disassembling of the 12 volumes of the Codex. Each sheet has then been positioned within “passe-partouts” cases, designed specifically to ensure the best conservation and to facilitate their exhibition at the same time.

From September 2009 until 2015, the year of the EXPO, the sheets have been displayed in different themes and rotated every 3 months. With the aim of creating an ideal tour of the most important works of this great Master still remaining in Milan, two exclusive venues were chosen: the Bramante Sacristy, jewel of Renaissance architecture, and the ancient Federiciana Room of the Biblioteca Ambrosiana, open to the public for this exceptional occasion.

Sala Federiciana

The Federiciana Room of the Ambrosiana is the ancient reading room of the Library. It was projected at the beginnings of the 17th century by architect Lelio Buzzi and then completed by Fabio Mangone.

The room still appears as the Cardinal wanted it to do. Together with his architects, he certainly examined Europe’s most modern libraries’projects with care, taking particular inspiration from Philippe II’s library at the Escorial in Madrid, introducing important innovations at the same time. As at the Escorial, in the Federiciana the reader’s desks were not separated, with an own window each, nor were the books locked to the desks. This allowed to have much more space for the bookshelves, which were running continuously along the walls. In order to optimize the available space, Federico chose to put a balcony half way of the walls, which was reachable using the stairs and which allowed to get to the higher shelves. At the same time he abolished the space for the windows at the ground floor. The illumination was assured by two big windows at the two sides of the big vault, so to keep the direct light away from the readers’desks. The vault itself, plastered in white, contributed to spread the light evenly into the room.

The Cardinal wanted to place a gallery of portraits of notable men at the base of the vault and on the balcony, so to prove the roots and the continuity of the catholic tradition. It is a series of portraits of saints and ecclesiastic people mainly, with a good presence of lay people too.

When the Ambrosiana was inaugurated, its collection consisted of around 15.000 manuscripts and 30.000 print art works, surpassing even older libraries: for example, the Biblioteca Vaticana’s printed texts collection was seven times smaller than the Ambrosiana’s one.

In a few years the Ambrosiana became a real point of reference for the whole Europe’s scholars, as the French writer and librarian Gabriel Naudè wrote in 1627: «Talking about the Biblioteca Ambrosiana…it surpasses all of the others [libraries] in size and greatness. Nothing is more extraordinary than [the thing that] everyone could enter the library at any reasonable time and remain there for all the time he wants to, consulting the documents of every author he is interested about. With no other difficulties, the visitor can get there during the normal working day’s opening hours, and ask the librarian, or one of his three assistants, for the books he wants to read. The librarians are well paid and well treated, so that they are always careful of what belongs to the Biblioteca and of the people who get there every day…».

Unfortunately in 1943 the Federiciana, together with other rooms of the Ambrosiana, was heavily damaged by the bombings: lots of fire bombs’ pieces pierced the room’s shields causing the collapse of the walls and of the bookshelves, and the consequent books’ incineration. It was then brought back to its splendour in the postwar years, but it remained usually closed until 2009, when it was chosen as the main exhibition hall for the Codex Atlanticus.

The Bramante Sacristy

The suggestive Bramante Sacristy in the convent of Santa Maria delle Grazie has been the exhibition venue of the Codex Atlanticus exhibition project since 2009, alongside the Federiciana Room of the Biblioteca Ambrosiana.

The monumental complex of the Sacristy, which also includes the cloister, is certainly one of Milan’s most fascinating hidden corners, still almost unknown to the great public.

In the early nineties of the 15th century, Ludovico il Moro, Duke of Milan, decided to launch an ambitious expansion and renovation project of the convent of Santa Maria delle Grazie, which was intended to become the mausoleum of the Sforza family. For this purpose, Ludovico relied on two of the greatest artists of those times, who were already serving at his court: Bramante, to whom he entrusted the task of building the lantern of the basilica and a new sacristy, and Leonardo, who was commissioned to paint the Last Supper on the north wall of the refectory.

The poor space available and the necessity to highlight the impressive lantern of the basilica, forced Bramante to build the new sacristy quite far from the church, so he connected the two parts with a small cloister of perfect Renaissance proportions that is still considered one of the most suggestive in Milan.

In 1947 the duchess of Milan, Beatrice d’Este, died prematurely and was buried in the choir of the “Grazie” basilica. This sad event made the completion of the renovation project even more urgent: by the end of the same year the little cloister and the sacristy are reported to be nearly complete, even though in 1499 the remaining expansion plans stopped suddenly after the fall of Ludovico’s Signoria.

The Sacristy, a large rectangular hall closed by a semicircular apse, hides many artworks and curiosities which cannot be missed. On the barrel vault Leonardo’s followers painted a suggestive blue sky, sprinkled with stars executed in pine resin and gold foil. This motif had been previously used for the ceiling of the hall of the Last Supper, which was unfortunately destroyed during World War II, whereas the two series of cabinets that run continuously along the side walls of the Sacristy were made at the end of the fifteenth century to keep the precious liturgical furnishings donated by the Moro to the convent after the death of Beatrice d’Este, now unfortunately lost.

The oral tradition says that along the left wall of the hall, where today you can admire a rare example of nocturnal clock, there was a secret passage connecting the Convent to the Sforza Castle, which was also destroyed during World War II.

Finally, the cloister is a real oasis of peace and harmony right in the centre of Milan and it is commonly known as “cloister of the frogs” because of the four frogs statues decorating the central fountain. The surrounding flowerbeds are adorned by wonderful specimens of star magnolias: their white flowers bloom in the month of March and stand out beautifully on the baked-clay decorations of the lantern and of the arcades.