Interview by Tiziano Thomas Dossena

A Guggenheim and Berlin Prize Fellow, a recipient of the Dorothea Lange/Paul Taylor Prize from Duke University’s Center for Documentary Studies, and the Bechtel Prize for Educating the Imagination from Teachers and Writers Collaborative, Mary Cappello is a former Fulbright Lecturer at the Gorky Literary Institute (Moscow, Russia) and currently Professor of English and creative writing at the University of Rhode Island. She is the author of six books and co-author of one, and she has numerous essays and articles published in professional and literary magazines, and anthologies. She kindly accepted to share her thoughts about her books and lifework with us…

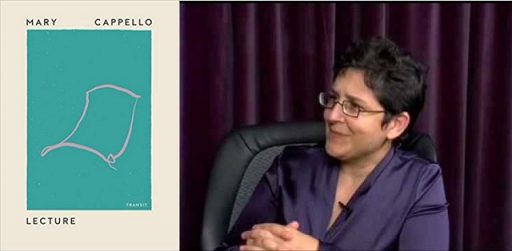

Her most recent book, “Lecture,” which appeared this October, has enjoyed a warm reception with features in such places as The Atlantic and The Los Angeles Review of Books. In September, she carried out a discussion of the project with novelist, essayist, and scholar, Namwali Serpell, hosted by Brooklyn’s Community Bookstore.

Mary Cappello: There’s a statement I find useful on the website of Columbia University’s Institute for Ideas and Imagination where they write that the purpose of the Institute is “to question the established ways in which knowledge is defined, produced, and taught.” That’s pretty much the point of my latest book. I’m very interested in what might be called “re-mediations of knowledge”—I want to pause to consider why we adhere unquestioningly to the forms that shape how and what we learn, how and what we convey or perform as writers or scholars, this includes everything from re-thinking the traditional panel presentation, to the public reading, from the conference to the syllabus. Each of these forms deserves a book in my opinion (or many books), at the least, a curiosity-imbued genealogy that might bring to the fore each mode’s historic, educational, and ideological supports. What purpose did these forms originally serve and how are they serving us (or failing to serve us) now? What might incite their re-invention, and how do the challenges of our current moment suggest the need for new ways to think about knowledge and understanding?

” …essayism seems to have capaciousness and curiosity hard-wired into its DNA.”

Mary Cappello: I think of each of my books as a different type of thought experiment—an approach inspired by Gertrude Stein’s life’s work, though my writing does not begin to approximate the radically experimental purview of hers.

The cultivation of wonder is very important to me, as is the pursuit of a kind of strange beauty.

I remember many years ago hearing the current Nobel Laureate, the poet, Louise Glück, say in an interview that with each new book that she wrote, she identified a habit that she sought self-consciously to break. While I doubt that I can claim to have succeeded in doing this with each new book that I have written, I have always been inspired by that directive, and I try to keep it nearby. I take a somewhat related approach with my students as well, suggesting that we treat each problem or question that compels us as demanding its own new relationship to form. I have also tried to take seriously something that a graduate school mentor of mine, Martin Pops, once wrote about Herman Melville. That, in Melville’s novel, Redburn, he “was doing what he could do easily rather than chancing what he could not.” If we have been working for many years at our trade, we know what we can do well. I do try to give myself over to compositional approaches that are foreign to me, or in which I have little confidence, even though I know that this could lead to failure.

As for wide-ranging subject matter, essayism seems to have capaciousness and curiosity hard-wired into its DNA. Everything is interesting! And there’s not enough time in any one writer’s life to tap even a tiny morsel of the infinite, but, still, we try.

“I was aware of the power and beauty of my mother’s voice from a very early age…”

Mary Cappello: I was aware of the power and beauty of my mother’s voice from a very early age, and, beyond that, of the role that reading and writing played quite literally in her survival. A certain relation to language, a reverence for the power of words, a love of the transformative potential of literature was bequeathed to me by people like my mother, Rosemary Petracca Cappello, a deep reader and a poet, and her father, a shoemaker-writer from Teano, John Petracca.

Night Bloom emerged out of an essay I had written ostensibly for a panel on autobiography at a Modern Language Association convention over 20 years ago. At the time, I was hopeful to create a form that could bring my poetic practice together with a scholarly ethos. I composed an essay that was rather unconventional given the protocols of academic panels. It was a personal essay on the subject of my mother’s having used letter-writing as a means of leaving the house during a period of my childhood in which she suffered from agoraphobia.

“…awkwardness was a wholly pervasive but woefully undertheorized and under-described condition.”

L’Idea Magazine: Your second book, “Awkward: A Detour” (Bellevue Literary Press), a Los Angeles Times bestseller, ranges across various subjects. Could you tell us more about that and what prompted you to write it?

Mary Cappello: I couldn’t have told that, by the end of a semester teaching a seminar in Documentary Discourse and Immigrant Subjectivity, “awkwardness” would appear before me as a subject and a form begging for a book. My experiences abroad in 2001-2002, in Russia and Italy respectively, in many ways served as a foundation for my pursuit of awkwardness, most especially because of a feeling of an inability to adjust to life in the United States upon my return, particularly in the year following the events of September 11th (I was teaching and researching in Moscow in Fall of 2001, and in Italy and Sicily in the Spring and Summer of 2002). Originally in search of a conceptual center around which a book set in Italy and Russia could cohere, I found in awkwardness this possibility but much more: a book-length essay that moves out from and returns to forms of national (and global) displacement, but that also follows awkwardness toward unexpected areas of investigation: a complex braid of conceptual kin overlaid with implications for how we live in our bodies, how we manage our souls, and what is at stake in an over-valuation of balance, fit, adjustment and calm. Talking about the book with people from all walks, stations, and classes of life, I realized immediately that awkwardness was a wholly pervasive but woefully undertheorized and under-described condition. Our inability to dwell in uncertainty following the events of September 11th, and our embrace, instead, of xenophobic reaction formations served as the political ground of the book.

In time, I would come to see awkwardness as the result of our desperate attempts to control chaos or our futile attempts to order things when they insist on falling apart. I’d become interested in the awkwardness of escaping feeling: you might try to numb yourself, but you’re left with a feeling, and the “feeling” is a feeling of awkwardness. And I would come to think of awkwardness as fundamental to our human-ness insofar as ‘being’ depends upon a great many inconsistencies and gaps that we daily try to avoid acknowledging. The gap between being alive and not understanding what it means to be alive is a kind of fundamental awkwardness. There’s no escaping it; we need to embrace it.

Mary Cappello: I like to say that Called Back is not “about” breast cancer but is written from it. Here are the things that cancer at the turn of the century was asking me to notice and here is what it didn’t want me to notice. Here is the thinking that becomes necessary and possible in the context of treatment for breast cancer. Educators in a variety of fields have taught the book—from classes in feminist memoir to courses in Medical Humanities, and it seems to speak to people at every level of the curriculum, as well as to physicians-in-training and of course fellow patients. The book is a cultural critique in the tradition of Sontag, Lorde, Ehrenreich, and Rose, and it’s also a kind of love song to my partner, Jean Walton, and my surgeon, Dr. Maureen Chung. I love to give readings from it and to discuss it, so I’m looking forward to its renewed life, especially in these dire pandemic times, and with gratitude to Fordham University Press’ choosing it for re-print.

Mary Cappello: Swallow is based on one of the most compelling collections in Philadelphia’s Mütter Museum—over 2,000 foreign bodies that a pioneering laryngologist named Chevalier Jackson extracted nonsurgically from people’s airways and stomachs in the early part of the 20th century. My encounter with this cabinet of curiosities was accidental, and originally I imagined simply writing an essay about the peculiar nature of the collection and its objects’ aura. But then I discovered that Jackson had written a best-selling autobiography in 1938, and once I read it, I was seduced by him, his life story, and my sense of him as an inventor, an artist, a writer, and humanitarian. He was an eccentric genius who saved thousands of people’s lives. I came to understand the collection as haunted by the stories that it could not tell on its own, and this led me down uncharted paths at the National Library of Medicine where a great many of the case studies attached to this collection reside. The book is a psychobiography of Jackson but it’s also an attempt to re-humanize the collection—which I subsequently played a role in re-curating and re-contextualizing. It’s a meditation on the fine line between that which we marvel at and that which disgusts us. Along the way, it tries to find a language for the complex bio-dynamics of the human swallow, and the mouth as the site of appetite, desire, aggression, and language itself.

Mary Cappello: I think of Buffalo as the city that tutored me in the importance of interiors and interiority, and SUNY/Buffalo’s English Department as the place where I came to know the extreme pleasure of thinking, not just alone and on one’s own, but with others—the relationship between thinking and sociality. The place was a cauldron of new ideas, and it was dedicated to a kind of radical originality, a quirkiness that helped me feel validated in my own odd turns of thought and imagination. No two professors in Buffalo’s English department thought alike, which might seem like an obvious thing to say, but it was very much the case that the professors I had the privilege to learn from were not much interested in orthodoxy, so even if a seminar represented a shared, new vanguard, which might seem, on the surface, predictable, what happened in these seminars never was. It was a place where the creative was never severed from the critical. A place where it wasn’t just ok but absolutely essential to think of oneself as a thinker-composer, or an artist-intellectual. Buffalo and the department were the places where I met James Morrison and Jean Walton, life-changers, forever. With both of them, I experienced “love at first sight.” Together, we wrote Buffalo Trace: A Threefold Vibration.

Mary Cappello: Many of my favorite books to emerge from a queer sensibility are books of three, from Gertrude Stein’s Three Lives to David Plante’s Difficult Women, to Hilton Als’ The Women to Roland Barthes’ Sade, Fourier, Loyola. Our contribution to this tradition is A Threefold Vibration. As a reader, there is something elegant and inviting about a book made up of three parts to me, and there’s also something tantalizingly asymmetrical about any collection of three. I have an abiding interest in the off-kilter or the questionably balanced.

The book is about the separate but overlapping routes we took to coming into consciousness as queer intellectuals in 1980s Buffalo. There are numerous themes that recur in the essays, but always from a different angle, and we hope that is the beauty of this project. These include the limits of expression, the gender of ambition, secrecy, eroticism, academic time, and snow. We also each inadvertently created portraits of one another, and especially first encounters. One of my favorite texts is an interview that the French philosopher Michel Foucault carried out in which he proposes that homosexuality’s real threat to the social order has to do with the new forms of friendship it makes possible. I hope that readers experience an uncommon kinship in the book not just between the three of us, but between themselves and us or the stories that we bring to the page in these essays.

One of the high points of bringing it out was the chance to have a conversation with the incomparable Michael Silverblatt for KCRW’s bookworm. Silverblatt’s own relationship to Buffalo’s English Department emerges in the interview as well.

Mary Cappello: Life Breaks In is probably my most ambitious book thus far, formally and thematically. I conceived of it as a collection of essays and other prose experiments. The book has numerous premises: for example, that mood is the basis for a lucrative pharmacology even though there is no agreement either in the hard or social sciences on what mood IS. That mood is one of those subjects that is everywhere apparent but under-thought. That mood appears to be an ineffable yet essential core of who we are. That in the US, mood is grossly de-delimited by the shrunken lexicon of depression. An article appearing in Salmagundi in which the great writer, JM Coetzee called for a psychology for our times that would take mood seriously spurred me on, as did the sudden, burgeoning interest in mood in the academy in literary and cultural studies (the work of Hans Gumbrecht, for example). My book aims to contribute to these discussions though it is not an academic book. First and foremost, I wanted to see if I could create a literary form that could do justice to mood. To test the boundaries of new nonfiction forms, the elasticity of the essay, the short form, the aphorism, all in the name of a subject that asks for its own form: mood. “Cloud-writing” might be the answer the book provides. The main point of the book is to create a vast repertoire of zones that readers can enter and exit as they please, and to spark a multi-disciplinary conversation, performative as well as meditative, on the subject of atmospheres, personal and political, psychological and aesthetic, real and imagined that govern or liberate us, by turns. In the process, I found myself unexpectedly bringing to light some undiscovered spaces where mood has done interesting work in the world (specifically, the picture books of Margaret Wise Brown; the habitat dioramas of Charles D. Hubbard in the LC Bates Museum; and Florence Thomas’ fairytale Viewmasters; a major through-line of the book is mood’s kinship with sound). In the end, I considered that the major point of the book might be to offer a form of strange beauty in mood’s name.

The book is not directly related to my doctoral studies except insofar as I have always maintained an interest in the workings of the human mind, encouraged by my study at Buffalo’s Center for the Psychoanalytic Study of the Arts. And, it is probably the case that I was drawn to the unique habitat dioramas of Charles Hubbard—a forgotten American impressionist—thanks to some of my formative training in Visual Culture under Martin Pops.

Mary Cappello: I’m working on a book-length essay along the order of my earlier book, Awkward: A Detour, but this time with a focus on dormancy, on all that sleeps and what stirs something to wake, psychologically, physiologically, and culturally/socially.

I’m also working slowly on a collection of short-form prose pieces that I am calling “studies” or literary études inspired by what feels like a diminishing ability to study anything at all in the digital age.

Meanwhile, I’ve been writing a series of long-form essays on the subject of intimacy between strangers, that includes, most recently, an essay on the many meanings of the word, “keep,” after seeing a sign on a house in my neighborhood saying “keep out,” considering what a strange command that is, and wondering what it could possibly mean, especially to a non-native speaker of English.

I recently curated a collection of e-mails of my mother’s, Rosemary Petracca Cappello, for Ninth Letter, called “The Dearest Mary Project”; and I had the privilege of composing a new Afterword to my third book, Called Back, in anticipation of its re-issue from Fordham University Press in Spring of 2021.

“This is what writing is to me—a humble, ethical act that I carry out in a workshop, largely in solitude.”

L’Idea Magazine: Could you tell about one or two of your essays that have been published in various magazines and why you felt compelled to write on those topics?

Mary Cappello: I think I’d like to draw your attention to two of my earlier essays, “Losing Consciousness to a Lost Art,” which appeared in Michigan Quarterly Review in 2008, and “Moscow, 9/11,” which appeared in Raritan in 2002. “Losing Consciousness to a Lost Art” materialized for me during screenings of silent film and the very special atmosphere that is created annually at Le Giornate del Cinema Muto in Pordenone, Italy. I have had the good fortune to attend the festival twice in my lifetime, and this essay emerged on the occasion of my first sublime experience of this week-long extravaganza. I was re-visiting the essay recently and realizing that it treats the very subject that is at the heart of my next book project. We think that we are moving on to new and different territory when we write, and hopefully in some ways we are, but this essay shows my abiding interest in how we sleep and dream and what we wake to, an interest that is at the heart of my next book project on dormancy and dormant states. The essay earned a Notable Essay of the Year citation in Best American Essays that year. “Moscow, 9/11” speaks to my experience living in Moscow, Russia, at the time of September 11th. I was teaching on a Fulbright fellowship at the Gorky Literary Institute and studying Russian at the time, and the piece is my attempt to offer a glimpse of what it was like to experience that historical cataclysm at a far distance from my homeland.

L’Idea Magazine: Is the teacher in you influencing the writer in you or vice versa?

Mary Cappello: The teaching and the writing always go hand in hand. Teaching is an art, and often enough I learn from my students; the classroom is often a cauldron for the testing of ideas, or for working through something I’m writing about, and things that arise unexpectedly in the classroom often directly feed my writing. My teaching career has enabled me to be present to and inspired by the truly great writing that many of my students have produced, both undergraduate and graduate, and, in some cases, to witness the meteoric blossoming of their own careers. This includes, perhaps most notably, the Pulitzer Prize winning playwright, Ayad Akhtar, who studied with me at the University of Rochester. At the time that we met, I was 29 and he was 19! It was so many years ago. His recent novel, Homeland Elegies, includes a character based on me and a fictionalized homage to our relationship.

“…the gardens I grew up in stood for willfulness, patience, and an abiding love of changing forms..”

L’Idea Magazine: Did you find your Italian American roots influenced your writing and your life choices? If so, how?

Mary Cappello: I think you can see from my earlier answers that my Italian American upbringing is at the heart of my writing. There are so many ways to talk about this, but it’s possible a line from my first book, Night Bloom, says it best. I was writing, in particular, about gardening in that book, that of my father (whose parents came from a town near Palermo, Sicily) and that of my maternal (Neapolitan) grandfather (whom I’ve already mentioned), and his father, who was a master gardener who made his living by, in summer, cultivating the gardens of the wealthy residents of Philadelphia’s Main Line, and in winter, stoking their furnaces. In either case, his job was to create warmth. In Night Bloom, I wrote that “the gardens I grew up in stood for willfulness, patience, and an abiding love of changing forms.” These principles guide my aesthetic as a writer. I have had to admit over the years that, in spite of the influence of master gardeners, I’m not a great gardener, try as I might! But I maintain an intense interest in plants and flowers and still hold out hope of studying Botany in earnest one day. The work of my gardener forebears, at any rate, manifest in the art that I try to make. As well, I place a high premium on all things artisanal as a result of my Italian American upbringing. The people who reared me were weavers and shoemakers, sheet metal craftsmen, hatters, and confectioners. I try to keep their handiwork nearby to help remind me that my writing needs to be embodied. But I also keep them near to remind me of the pleasures, power, and necessity of honest labor. This is what writing is to me—a humble, ethical act that I carry out in a workshop, largely in solitude. It’s a making and attending that serves something other than oneself. I also try to stay present and true to their stories and their complexly beautiful lives all the while knowing that I can never do justice to them—their lives are boundless, really—but I still try.

“I’d like to live in a country where those entrusted with governance recall once more their dedication to the public good…”

L’Idea Magazine: What is your utmost desire at the moment?

Mary Cappello: That a new day will dawn in which we will collectively be enjoined to turn our attention to the things that need fixing, the lives that need our attention, the issues that truly matter in lieu of the daily antics and attention-grabbing inanities of a person who strikes me as a deranged and extremely dangerous individual—the current president of these United States. Someday, he will, like all of us, discover that he is human—which is to say, he, too, will have to face the limits, rather than the extent, of his powers. He will know that he is not omnipotent but, like us all, mortal. This must also be said of all those who aided and abetted him. I’d like to live in a country where those entrusted with governance recall once more their dedication to the public good over and against the acquisition of a new blue suit and a deluded sense of their own power and importance. Currently, I’m put in mind of the painstaking work involved by people who took the splinters, shards, and smashed pieces of the Jewish synagogue in Berlin and re-built it following the War. In our case, it’s not just about putting things back together—which will be hard enough—but re-conceiving of structures that, in a very real and good sense, we have been finally required to understand as deeply flawed. If demagoguery wins the election, my utmost desire will be to find my place in the revolution that will, of necessity, follow, while maintaining my own humanity, which is to say, my own sanity.

L’Idea Magazine: Do you believe that the isolation that Covid19 has forced most of our society into has been a boom for writers or it had a deterrent effect on creativity?

Mary Cappello: I don’t think it’s an either/or. I think it has required that we reconsider where and how we make meaning. And my own desire is to be quiet for a very long time. I have not written anything worth sharing with a public since the day on which the pandemic was announced, I remember it vividly: the 12th of March 2020. For my own part, I await the new language that I think is called for to meet the realities of this moment. I’m sure it will come, but I prefer not to rush it.

L’Idea Magazine: If you could meet any one historical character, who would he or she be and what would you ask them?

Mary Cappello: I’d like to sit at the feet of Hannah Arendt and ask her to help me to understand how we have arrived at this moment in the history of this nation-state.

L’Idea Magazine: A message for our readers?

Mary Cappello: I look forward to the day of our having survived the pandemic and being able to visit Italy and Sicily once more. To be in the presence of Italian and Sicilian culture, Italian and Sicilian people, Italian and Sicilian language, and Italian and Sicilian history once more. Such abiding beauty. I say this, and yet must pause in the presence of my own mis-spoken-ness, because, so much is unsaid in that little word, “our”—“our” having survived the pandemic. So many have not survived; people close to me and to you have already contracted the virus, are currently sick, or dying, or have died. Precariousness continues to loom; and even if we take every precaution—which we must—none of us is immune. May we continue to mourn in solidarity for a better day, and trust in the prospect of one day being able to greet each other in person, sharing the bounty of an Italian table.