Interview by Tiziano Thomas Dossena

Marianne is an avid traveler and an accomplished home cook. She shares family photos and recipes of dishes described in the book on her website, https://mariannerutter.com.

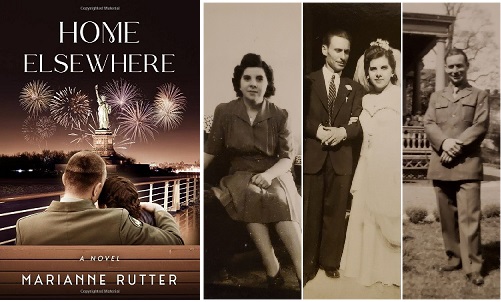

Home Elsewhere is her first novel.

L’Idea Magazine: Hello Marianne. I read your book, “Home Elsewhere,” and found it fascinating. What inspired you to write the book? Did you have any factual data on which to base the story? If so, was it difficult to separate facts from legends?

Marianne Rutter: As I mention in my author’s note to Home Elsewhere, my father told me of his POW experience only once, when he accompanied me on a five-hour drive to Hartford, Connecticut to visit his brother, my uncle Joe (after whom, incidentally, I modeled another character in the book). In this reticence to share his memories, Dad was typical of veterans of the Second World War, Tom Brokaw’s “Greatest Generation” no matter their nationality, who simply wanted to get on with life when the war ended: they spoke very little or not at all of their wartime exploits, however heroic. (Watch the acclaimed William Wyler film “The Best Years of Our Lives” (1946) for a poignant depiction of returning veterans struggling to readjust to daily life in America.) Understandable as that silence about their wartime experience was, I was additionally hampered by the fact that my father was no longer alive when I was writing the book to confirm aspects of his story.

Most significantly, I realized most people didn’t know about Axis prisoners on the home front during the war. Stories like my father’s – stories of nearly half a million Axis prisoners, 51,000 of them Italians, who spent a good portion of World War II in the United States – had largely gone untold. That gave me another reason, even more compelling, to write Home Elsewhere.

“I wished, in countless moments during the writing process, that I had asked my dad to tell me more about the war…”

L’Idea Magazine: So, we can safely say that your book belongs to the Historical Fiction category. Was it satisfying to write down a fictionalized memoir of your father?

Marianne Rutter: Yes, very satisfying indeed! I thought a lot about my dad as I wrote this book, and wanted to understand his motivation to emigrate to America after the war – after all, it was a country in which he was held prisoner. In the process of writing Home Elsewhere, the core of the immigrant story engaged my imagination at every step. I kept my parents’ wedding picture at close hand as I wrote the chapters about their marriage in Sicily. After the book was mostly written, I came across an old photo album with snapshots taken by my aunt Josephine, lovingly preserved and meticulously dated during the war years. In an eerie coincidence, some of the photographs portrayed scenes I’d described from memory in the book.

“To set the mood as I wrote, I would often listen to the music of the “Big Band” era…”

I chose to write a book of historical fiction rather than an outright memoir precisely because I couldn’t verify precisely some key points, locations, and dates in my dad’s account. Writing fiction gave me the freedom to create characters based on – but not precisely like – the real-life individuals, placing them in a historical time and place that I could research. I wanted the fictional landscape of the book to be not only interesting but historically plausible. To set the mood as I wrote, I would often listen to the music of the “Big Band” era –American Songbook tunes by Cole Porter and the Gershwin brothers, recorded by the likes of Duke Ellington, Tommy Dorsey, and Benny Goodman.

Also, as a reader, I am a longtime fan of historical fiction, and I wanted Home Elsewhere to have reader appeal. The genre can evoke a more universal sense of the time and place that cannot always be gleaned by raw facts or mere dates. Fiction gave me the freedom to create characters that were neither quite out of whole cloth nor two-dimensional stand-ins for the real people I’d known and loved. Because they were fictional, the characters’ lives could diverge from my parents’ personal experiences to satisfy the demands of plot and dramatic tension, or to create a plausible storyline where there were breaches or disparities in the family legends that I knew.

“Since I didn’t know their actual history on this point, my unanswered questions became the dramatic tension in the story, and I invented plausible motivations for my characters…”

For instance, when the subject of returning to Italy comes up, our protagonist Giampaolo is forthright with Eleanor about wanting to discover what had happened to his family in Sicily during his wartime absence. I like to think my dad was worried, too, and eager to return home, but he never talked about it. Quite the contrary – he did talk frequently about enjoying his life in America, almost as if he’d closed the book on his life in Sicily.

Be that as it may, during my several visits with my Sicilian family, I know they counted him very lucky to have been able to emigrate after he married my mother. I believe he did, too. In the story, the fictional character Giampaolo was going to be repatriated back to Italy in any event; To heighten dramatic tension in the story, Giampaolo leaves with no firm commitment to marry Eleanor. The couple still has some unresolved issues: Eleanor has told him she was unwilling to return to Sicily to live, and in any case, her mother already opposed the marriage on those grounds. Between these truths, I encountered one of the critical gaps in my parents’ story where fictional invention aided the plot line. Other couples in this situation at the time became engaged or exacted a promise of some kind from each other, working through the logistics before being separated. I don’t know if my parents were among them. In any event, they never told me how they’d left things when my father went back to Sicily. Since I didn’t know their actual history on this point, my unanswered questions became the dramatic tension in the story, and I invented plausible motivations for my characters. That was fun, and very liberating for a novice writer.

L’Idea Magazine: Could you give us a synopsis of the story?

Marianne Rutter: Certainly. It is the fall of 1942 and Giampaolo Stagno is starving. A soldier in the beleaguered Italian Army, the young Sicilian is captured and shipped from North Africa to the United States as a prisoner of war, assigned to a POW camp in New Jersey.

A hundred miles from the camp, in Pennsylvania, Eleanor Fazzio is also starving—for a different life. She works in a textile mill and returns home each day to her mother and cousins and their close-knit Italian American immigrant community. War has limited the possibilities for a thirty-year-old woman in Eleanor’s corner of America, and she longs for another kind of life.

Giampaolo and Eleanor know nothing of each other, though they share the customs and dialect of their island homeland, Sicily. Fate conspires to bring the couple together: their common heritage, shaped thousands of miles apart, forges a tentative bond between them. But the vagaries of a world war and its aftermath drive them apart, thrusting the pair into an uncertain future.

“As I started writing and verifying Italian words in the manuscript, I became aware that I hadn’t really heard Italian as a kid, but rather a Sicilian dialect…”

L’Idea Magazine: In the book you use the Sicilian dialect (with proper English translation) to enrich the conversations between the Italian POWs and the American girls. I found it to be very charming and useful to create the proper atmosphere for the reader. You also have a glossary of Sicilian terms at the rear of the book. Did you have difficulty finding the proper spelling of Sicilian words? Did your parents speak Sicilian at home? Were you ever in Sicily?

Marianne Rutter: I liked the idea of using the Italian language in the book to set the scene and create a texture of idiomatic interest. I wanted to get across the bilingual nature of these relationships and insert a bit of my own experience growing up.

As I started writing and verifying Italian words in the manuscript, I became aware that I hadn’t really heard Italian as a kid, but rather a Sicilian dialect. Researching the language was another aspect of my research, and in this, online spaces were very useful. I encountered several social media platforms where Sicilian phrases were translated, as well as links to entire Sicilian-English dictionaries that made the job much easier. But I still didn’t want my readers to have to work too hard with a language unfamiliar to them. So when my editor and several readers of the manuscript suggested that I include a glossary of Sicilian dialect words and phrases at the back of the book, I eagerly embraced the idea.

As for travel to Sicily, I’ve blogged at some length about my Sicilian travel on my website (https://mariannerutter.com/blog?blogcategory=Travel). I have been lucky to have visited Sicily at all stages of my life, the earliest as a child in 1960, when my parents took my sister and me to a 50th wedding anniversary celebration for my paternal grandparents: it was the only time I met Nonna and Nonnu. I returned again as a young adult in 1977, and yet again in 1988 with my parents, my husband and our 5-year-old daughter. Most recently, I returned in 2017 with both of my children. A big component of the last two visits was to play the tourist since I had not done so before. The many-layered history of Sicily is evident in its very landscape: spectacular classical ruins, charming small towns and ancient cities surrounded by beaches, cliffs and crystalline waters.

L’Idea Magazine: Your book is about Italian Prisoners of War and the kind of relationship they built here in the USA. Did you have to do a lot of research for the book? Was there anything that you found unusual from the information you gathered?

Marianne Rutter: Because little had been written on the topic of Italian POWs, the topic was difficult to research. Google searches would typically return information on Japanese-American internment on the West Coast during World War II, about which much more has been written. Eventually, I found a couple of published works and several online sources written by professional historians that proved valuable in helping me to create a historically accurate story about Italian POWs. I note these in my acknowledgments at the back of the book.

Beyond what I’ve already described above, most of my research involved finding the answers to specific questions – a process greatly aided by the internet. This is not an academic book but a work of fiction; still, I wanted to get the history right.

Among the most significant thing I learned was the crucial role played by Italian Service Units in enabling greater interaction between Italian POWs and the Italian American community on the home front.

After Mussolini was deposed in 1943, Italy signed an armistice with the Allies, essentially After “switching sides,” from Axis enemy combatant to Allied collaborator. The impact of the Italian armistice was global in scope: Allied countries all over the world were housing Italian POWs and together they were compelled to find a diplomatic solution and a new set of rules governing these now-no-longer-prisoners, in the legal sense of the word. The result: Italian Service Units.

It was a voluntary arrangement. Italian soldiers pledged to assist the Allies in winning the war, or at least not stand in the way. About 90% of them did so. The remaining ten percent, mostly officers, retained their POW status but were remanded to more remote camps and posts to thwart any overt efforts at espionage.

The commitment exacted on prisoners by the ISU pledge was not as draconian as it sounds. ISU members weren’t expected to put themselves in danger or commit treasonous acts; they merely agreed to not impede the progress of the Allies winning the war. Of the ones that joined ISUs, very few prisoners possessed special skills or still-active contact with enemy combatants in their home country that would be of value to the war effort. A handful of Italian POWs who had been radio operators made a few broadcasts in Italian on behalf of the Allies from the radio station at Madison Square Garden in New York City.

Joining an ISU meant an improved standard of living for the typical prisoner, undoubtedly making the Italian soldiers’ stay in America more palatable and positive. Instead of scrip usable only in exchange for goods at camp canteens, Italian prisoners were now paid in U.S. dollars: $8 cash per week was considered standard. ISU members were also allowed to take field trips and excursions outside the camps, as the book describes, sometimes with American GIs from the camps, but just as often organized by local Italian Catholic parishes. Some ISU members, especially those with relatives in the U.S., received weekend leave to visit family – always chaperoned by American GIs (often Italian-American and bi-lingual themselves). I portray several such outings in Home Elsewhere.

In short: if it hadn’t been for the ISU policy, my father would probably not have met my mother!

It’s unsurprising that romance bloomed between the Italian men and American women, many of the latter group immigrants from Italy themselves. Stricter post-war immigration quotas necessitated American women to travel to Italy to be married so that the new Italian spouse could become an American citizen. Many, like my parents, emigrated promptly thereafter.

“I felt safe and loved; looking back on those times, I now realize I was also sheltered and pampered. But first and foremost, I was expected to be busy…”

L’Idea Magazine: Your book is also about love; a love that conquers all. Did your parents’ love mirror the love of the two main protagonists of the storyline? Is the description of the characters very similar to the aspect of your parents or is it completely fictional?

Marianne Rutter: Let’s remember that the main characters in Home Elsewhere are young and single, so of course I have no actual memory of my parents before they were married. So I devised a plot that paralleled the timeline of my parents’ early life as a couple when they were courting. Since my parents didn’t reminisce much about that part of their lives, I didn’t have many real facts to go on. I invented most of the love story in order to craft a cohesive plot. In sum, the budding romance between the fictional characters in my book is what I imagined for my parents; it’s my gift to them.

That said, as a child, I witnessed a contented but only occasionally demonstrative relationship between my parents. Our home was a no-nonsense environment where work and responsibility were high on the list of expectations. There was plenty of overt affection – hugs and kisses of the sort Italians do in a matter-of-fact way, when greeting just about everyone. I felt safe and loved; looking back on those times, I now realize I was also sheltered and pampered. But first and foremost, I was expected to be busy, to pull my weight even if it was only a two-pound textbook. If I was found idle, the situation was promptly remedied. (“Did you practice your piano?” “Don’t you have homework to do?”) The household I describe in the book was very like the one in which I was raised: specific chores for one and all, everyone playing a role in the smooth functioning of the household. I found it very satisfying to recreate domestic scenes from my memory and wo celebrate hometown places I remember in Home Elsewhere.

L’Idea Magazine: You have a website, MarianneRutter.com, in which you talk about your book and Sicilian culture, among other things. In one of your posts, you state that Sicilian heritage is underappreciated. Could you explain that statement?

Marianne Rutter: The perception exists that Sicilian culture and heritage are familiar to us all. In reality, I believe that Sicilian and Sicilian American heritage are misunderstood, and we have a lot of work to do to correct the record. When people think of Sicily and Sicilian-Americans, the Mafia is regrettably the first thing that comes to mind. “The Godfather” gave renewed energy to a violent stereotype that lingers and is extrapolated to Sicilians generally and to all things Sicilian. Everyone remembers the line from the film, “Leave the gun, take the cannoli,” or the grisly image of a severed horse’s head. This dialog and these images taint the overall perception of our heritage and obscure some of the film’s better moments.

To be sure, “The Godfather” was a signal artistic contribution to the American canon of film (full disclosure: I’m a fan). The combined creative geniuses of Puzo and Coppola are just to be celebrated. But money talks: so prolific was the film’s success that it spawned an entire subculture of “Mafia entertainment” sprawling over several decades – think of other Mafia-themed movies like “Goodfellas” and “The Irishman,” or the hit television series “The Sopranos.” Yet we forget that that fame – notoriety, really – was purchased by promoting and glorifying a criminal element of Sicilian society that, ignominious and tragic as it was, actually plays a very small part in the sweep of Sicily’s history and culture.

What “The Godfather” films ought to be remembered for is their focused attention to Sicilian authenticity. This is what I love about them. Authentically Sicilian moments are inevitably overlooked, such as when, in the first movie, Michael Corleone’s beautiful Sicilian bride Appolonia makes the time-honored traditional rounds of their wedding guests, spooning Jordan almonds into their waiting palms. Several frames later in the bedroom scene, as she embraces her new husband, the viewer observes the bride’s thick wrists, the talismans of a Sicilian peasant woman. For me, the second film’s most memorable impression is the precise Sicilian-American dialect, accurate down to the last syllable, on view in the Lower East Side scenes as the young Vito Corleone seals a deal with Tessio and Clemenza at the kitchen table or learns how to steal a rug.

” Imbued in me from early childhood was the assumption that I would go to college …”

Regrettably, there is still a Mafia cloud over all things Sicilian. I take offense now when I lay proud claim to my Sicilian-American heritage, and even good friends (usually non-Italians) smirk and make remarks about the Mafia, as if some criminal skeletons lurk in my closet.

A more exacting and pleasant route through which to appreciate Sicilian culture is to appreciate its food. It’s also thoroughly Italian to do so! In Sicilian recipes that celebrate the glorious bounty of its farmlands and the surrounding sea, you can find strains of influence that are Greco-Roman, Norman, North African, and Bourbon French. Or, appreciate Sicily through its diverse landscape: in the variety of architecture in the eastern and western sides of the island, you find a roadmap to centuries of successive colonization by diverse cultures, each of which left its mark on modern-day Sicily.

Or, better yet: if you haven’t already done so, read John Julius Norwich’s brief, brilliant history, Sicily: An Island at the Crossroads of History.

L’Idea Magazine: How much did your Sicilian heritage influence your life decisions in general?

Marianne Rutter: That’s hard for me to answer. Looking back on my younger self now, I realize that my earliest influences were a set of paradoxes. Imbued in me from early childhood was the assumption that I would go to college – this from parents neither of whom had more than middle-school education themselves. Also was a stubborn insistence to blend seamlessly into the American way of life. I grew up in a household where I heard another language, yet I was discouraged from speaking it myself. Our dinner table was graced with delicious ethnic food, surrounded by a nuclear family that included aunts, uncles, a grandmother-matriarch – a very ethnic arrangement – yet the Sicilian-American backdrop of our lives was implicit, understated. As a family, our socializing was almost exclusively with other Italian Americans (cousins and other relatives; yet we were supposed to be weaving our way into the American fabric of life.

I knew that I was supposed to respect my Sicilian heritage but not wear it on my sleeve. I was expected to assimilate – to become American – with all due speed, but there was always a pull back toward the known Sicilian-American way of life.

A big part of assimilating meant having a name that would also “blend in.” For my mother, it was very important to signal this to relatives still in Italy. Tiptoeing just to the edge of Sicilian tradition, my ‘normal’ American-sounding first name (Marianne – English spelling), was nonetheless the name of a great-grandmother, while my subtly unpronounceable middle name (Concetta) was as Sicilian as it could be.

So it wasn’t until I was well into my twenties and married that I found a real cheerleader of my Sicilian culture – in, of all people, my Yankee-to-his-shoelaces husband. Matthew had come from privilege, had traveled widely, and attended exclusive private schools. He was not one shred Italian, but he was a “college man” – the latter virtue canceled out the deficit, in my mother’s eyes at least. Upon first meeting, he was unaccountably charmed by my family – a result that initially astounded me – and the charm very soon went both ways.

“Many representations of Italian American life are very two-dimensional – too much so to satisfy me….”

I believe Matthew’s deep appreciation for my cultural heritage stemmed from its very “otherness”; he had grown up in such a different, full-sized American world. But he had had some memorable encounters with Italy and with Italians at a young age, and he generalized from those positive memories to great warmth and curiosity about my family and our traditions. Seeing my Sicilian heritage through his eyes made me cherish it.

L’Idea Magazine: Do you intend to keep on writing or was this book a once-in-a-lifetime experience?

Marianne Rutter: I’m working now on a prequel to Home Elsewhere, an immigration story involving characters from my first book.

L’Idea Magazine: Do you believe the media in general presents the Italian American in a fair manner?

Marianne Rutter: Many representations of Italian American life are very two-dimensional – too much so to satisfy me. Italian Americans are not a monolith, no more than any other group of people. How we are portrayed in the media, as accurate or amusing as some of these portrayals may be, precludes the possibility of seeing us as complex, diverse individuals.

L’Idea Magazine: Who is the person who influenced you the most in your life?

Marianne Rutter: My parents were my single greatest early influence, for many of the reasons I shared earlier. It’s no small coincidence that they are the subject of my first book. And as the best life-mates should be, my late husband Matthew influenced my life in countless ways over more than forty years, not least in investing my heritage with new meaning. We met as college kids from very different backgrounds but we grew up together in the truest sense of those words.

L’Idea Magazine: If you had to define yourself with three adjectives, what would they be?

Marianne Rutter: Optimistic. Energetic. Tenacious.

L’Idea Magazine: If you could meet and talk to anyone in the world, from the past or the present, who would that person be? What would you like to ask them?

Marianne Rutter: There are so many! I would have to have a very big dining table to accommodate them all. Here are two random choices:

I would like to have met Thomas Moore, the Catholic saint, and contemporary of Henry VIII, the monarch who ordered his execution. More’s Utopia influenced my thinking while I was still in high school, and I would love to have heard him expound upon those themes.

I would love to have had a conversation with James Joyce, whose writing brought me to Dublin as a college student and invoked a much wider appreciation of Irish writers, Irish history and culture. He was an eccentric genius who also had a daughter named Lucia.

L’Idea Magazine: Any pastimes or hobbies?

Marianne Rutter: I am a voracious reader, particularly partial to historical fiction. (No surprise there.)

For relaxation, I love to play the piano, a skill I began learning at five and have been enjoying all of my life.

Taking solo walks is something I love to do, not just for the exercise and fresh air but for productive “thinking time” for my writing.

L’Idea Magazine: After having written a book like yours, do you have any suggestions for any of our readers who want to immortalize their life or the lives of their loved ones?

Marianne Rutter: Start by journaling your memories. Talk to your family, especially anyone who might have done a genealogy. See where that takes you.

L’Idea Magazine: A message for our readers?

Marianne Rutter: Be in touch with other Italian Americans beyond your family – I am in an Italian conversation class once a week with others who share my heritage It always reminds me how much we have in common, and besides – what fun we have together!