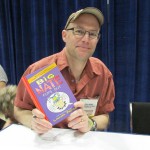

Lincoln Peirce (pronounced “Purse”) is an American cartoonist, best known as the creator of the Big Nate comic strip. Peirce was born in Iowa, grew up in Durham, New Hampshire and attended Colby College in Maine. He earned a graduate degree from Brooklyn College and studied at The Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture. He taught art and coached baseball at Xavier High School, a boys’ high school in New York City, for three years before moving to Maine in 1992.

Big Nate debuted in 1991 and appears in 300 newspapers in the US and online daily at www.gocomics.com, and is featured on the website Poptropica, www.poptropica.com. A fan and collector of classic country music, Peirce also hosts a local radio show devoted to Honky Tonk and Western Swing music on local station WMPG.

In addition to the Big Nate comic strip, Peirce is the author and illustrator of the New York Times bestselling Big Nate novel series. His Big Nate books have been featured on “Good Morning America” and in the “Boston Globe,” the “Los Angeles Times,” “USA Today,” and “The Washington Post.”

LINCOLN PEIRCE: I became very interested in comics, particularly newspaper comic strips, when I was about 7 or 8 years old. That’s not unusual; lots of kids like comics at that age. But only a handful of those kids take the next step and begin creating comics of their own. Once I began experimenting with inventing my own stories and characters, I started to consider the possibility of making cartooning my profession. When I look back on my trajectory, though, it’s clear to me that I didn’t devote as much time to developing my drawing skills as some of my peers did. I didn’t have the patience or the self-discipline to really practice my drawing; I just wanted to be able to draw well enough to tell the types of stories I was starting to write. If you split cartooning into a writing part and a drawing part, it’s always been the writing that’s come easier to me.

L’IDEA: How did the comic strip Big Nate came about and where does the name come from?

LINCOLN PEIRCE: First, the name: it’s the nickname I gave my brother, Jonathan, when we were boys. I’ve always liked the name Nate.

The strip itself evolved from an earlier idea called “Neighborhood Comix.” It was a strip that was based on the little neighborhood in New Hampshire where I grew up, and it featured a large cast of characters, including two brothers, Nate and Marty. Nate was the quiet straight man and Marty, the younger brother, was the jokester. Their relationship was reminiscent of the one my brother and I shared as boys. I submitted “Neighborhood Comix” to all the major syndicates and got some very nice feedback from Sarah Gillespie, the comics editor at United Media. She was to become my first editor. Her suggestion was that I choose one character and make that character the focal point of the strip. Well, I wanted to somehow keep both Nate AND Marty. So I kept the name Nate, but gave him a personality more like Marty’s – energetic, wisecracking, and occasionally troublemaking. And because Nate was now clearly the star, I renamed the strip “Big Nate.”

L’IDEA: Could you tell our readers about the Longest Cartoon Strip by a Team World Record that Big Nate has just set?

LINCOLN PEIRCE: That was an idea proposed by HarperCollins, the publisher of the Big Nate novels. A lot of kids have discovered Big Nate in recent years through those novels, and they learn only later that Big Nate has been a comic strip character for 23 years. With Nate’s comic strip roots, it seemed that trying to break the world record for the Longest Comic Strip by a Team was a great fit. HarperCollins reached out to schools via the Big Nate website and invited them to create individual panels for what would be a record-setting comic strip based on the first two Big Nate novels. And it worked beautifully. We assembled all the panels on the “Today” show in New York City in April, and the completed strip was something like 4,000 feet long. It was a great way to involve a lot of Big Nate readers in the process, and now kids all around the world can say they were part of setting a world record.

LINCOLN PEIRCE: For many years, Big Nate was what I’d call a moderate success as a comic strip. It was in about two hundred newspapers and it had a small, loyal readership. But it wasn’t widely known. I always thought that if I could just find a way to reach more readers, especially young readers, they’d like Big Nate. But I never considered writing novels; I was just looking for ways to get my comic strip into more newspapers. Then Jeff Kinney started writing his “Wimpy Kid” books, and suddenly every publisher in the world was looking for books that combined text and comics. Well, Jeff and I have known each other for many years, and he was kind enough to open some doors for me in the publishing world. I submitted proposals to about eight publishing houses, I guess, and HarperCollins made the best offer.

I’d never written a novel, but since I’d been doing the comic strip for almost twenty years at that point, I felt confident that I could create longer stories for those same characters. I just had to get used to the pacing. A 4-panel comic strip has a real rhythm to it, and I’m very accustomed to writing jokes and dialogue that correspond to that rhythm. But a 216-page book has a completely different rhythm, obviously. I had to figure out when and where the story needed to speed up or slow down. I had to make sure I was timing everything correctly, so that all the story threads would be resolved by the end of the book. And, of course, I had to write a lot of text instead of just putting everything in speech bubbles. It took a lot of getting used to, but I was pleasantly surprised by how much I enjoyed writing novels.

L’IDEA: Nate Wright, the protagonist of your strip, is also an aspiring cartoonist. Did you somewhat model him on yourself and your early experiences as cartoonist?

LINCOLN PEIRCE: Oh, of course. Nate isn’t based on me – he’s not an autobiographical character, in other words – but he shares many of my enthusiasms, obsessions, and pet peeves. And, as you mentioned, he’s a cartoonist. Some of Nate’s cartoon inventions, like “Doctor Cesspool,” are actually characters I created myself when I was a child. Drawing Nate’s comics enable me to indulge that part of my sensibility that’s still firmly planted in middle school. I get to draw the way a 6th grader would draw, and write the kind of jokes a 6th grader might write.

LINCOLN PEIRCE: There are plenty of connections. Nate’s pal, Francis, is based on a student I had when I was a high school art teacher. The dog next door, Spitsy, is a dead ringer for the dog that belonged to my best friend when we were growing up. Other characters are amalgams: Coach John looks a bit like my high school gym teacher and acts a lot like a baseball coach I played for. Mr. Rosa is a combination of several teachers I had over the years – guys whose hearts were in the right place, but who were starting to get burned out after spending 10 or 20 or 30 years in the classroom.

There have only been one or two times when I’ve made a concerted effort to create a character who looks like a real life counterpart. The most successful was a substitute teacher who was modeled on my friend and fellow cartoonist, Corey Pandolph. It actually looked quite a bit like him. But I’m no caricaturist.

L’IDEA: Has Nate Wright changed his physical appearance from his first entrance into the world of comics? (If so, how much and why?)

LINCOLN PEIRCE: All comic strip characters change over time, because the cartoonist’s drawing style inevitably evolves as the years roll by. In my case, I couldn’t draw very well when I started the comic strip in 1991. At the time, I didn’t realize how weak my drawing skills were, but now it’s difficult for me to look at the strips I did in the early and mid 90’s without feeling kind of embarrassed.

In 1991, Nate was skinnier and lankier than he is now. Over the years, without really realizing that I was doing it, I gradually made him shorter and more compact. I’m much happier with the way he looks now – he’s more expressive, and I can draw him more consistently – but height-wise, he’s not as tall as a sixth-grader would be in real life. He looks younger than he is. But I can live with it.

L’IDEA: Did your experience as a teacher help you a lot in creating the school environment in which this cartoon strip thrives?

LINCOLN PEIRCE: I’m sure it didn’t hurt. But I taught in an all-boys high school, so the students were several years older than Nate and his classmates. I rely much more on my own memories of sixth grade than on my experiences as a teacher. For whatever reason, I have almost total recall of events that happened when I was 10, 11, 12 years old. I remember those times more vividly than I do my teens or my twenties.

Schools are funny places, and middle schools – which where I grew up meant 6th, 7th, and 8th grade – are especially hilarious. Nate’s in 6th grade, which is a time of major transition. As a 5th grader, you have only one teacher, you hang your coat and put your lunch box in a little cubbyhole…you’re in a sort of bubble. Then you go to 6th grade, and you’ve got a different teacher for each subject. You’re sharing a locker with some kid you don’t even know. You’re surrounded by 7th and 8th graders who, in many cases, are much bigger and stronger than you are. You go to school dances. You play intramural sports. Each and every day, there’s the possibility of experiencing soaring triumphs or crushing humiliations. There’s a lot of comedic fodder there.

L’IDEA: Nate’s father is a divorced, single parent. Where is Nate’s mother? Has she appeared in any strip at all? Do you believe that her obvious absence from his everyday life influencing his behavior? Would he be any different if he lived in a two parents’ household?

LINCOLN PEIRCE: Nate’s mother has never appeared in the strip. When I launched the strip in 1991, I made a couple of early references to the fact that Nate’s parents were divorced. I envisioned the strip as a “domestic humor” strip when I started it, and I imagined that at some point I’d bring Nate’s mom in as a character. But very early on, I realized that the stories and jokes I enjoyed the most all revolved around Nate’s school life, his classmates, his teachers, and so on. With Nate’s dad and sister assuming somewhat diminished roles, I decided that it wouldn’t make much sense to introduce an estranged mom character.

I can’t say how it might change Nate’s behavior to be living with two parents. Nate’s dad is somewhat hapless at times, and it’s hard to imagine Nate’s mother being equally inept as a parent. So the dynamic would change, even if I didn’t intend it to. That’s why I have no plans to bring Nate’s mom into the strip, or to create a “significant other” for Nate’s father.

LINCOLN PEIRCE: I’m working on the seventh novel right now. It’s going to be called Big Nate Lives It Up. All the writing is done, and I’m doing the finished drawings. There’s also a Big Nate musical that will be touring this fall. The show was originally staged at Adventure Theater in Glen Echo Maryland in the spring of 2013, and it was so well received that a touring company is being assembled.

There are occasional rumblings about a Big Nate TV show or movie, but nothing has come together yet. And that’s fine with me. I’m very content with the way things are.

L’IDEA: You have been publishing Big Nate for over 23 years now. Do you find it difficult to come up with new ideas?

LINCOLN PEIRCE: I still haven’t run into a prolonged case of writer’s cramp on the comic strip, but there’s no doubt that the novels are becoming more challenging. There are only so many themes involving a 6th grade boy that are substantial enough to carry a whole book. When you write a book series, it’s a real challenge not to repeat yourself. Your readers, who are kids, expect certain elements. There’s got to be conflict, either with teachers or with other kids, because conflict is what makes a story interesting. There’s got to be a lot of physical humor, because slapstick is a huge part of comic storytelling. And there’s got to be a happy ending. I’m finding it increasingly challenging to meet those criteria in a fresh way in each book.

LINCOLN PEIRCE: I wrote three shorts under the title “Uncle Gus” featuring a cast of eccentric characters: a middle-aged loser, his loyal horse, his overly theatrical nephew, and a mysterious tiny con man named Ali Ali. In retrospect, I think they worked much better as long-format comic books than as animation. I also wrote a short called “Super John Doe Jr.,” about a kid who’s the son of a famous superhero but who’s inherited none of his father’s super powers. The best shorts I wrote were a series of 2-minute pieces for a short-lived Cartoon Network show, “Sunday Pants.” They were called “The Brothers Pistov.” They were two very angry Russian dogs. Gregor was completely deadpan but very passive-aggressive. The other, Anton, was insanely volatile and violent.

Writing for TV is a completely different style of writing from what I usually do. Think about your basic 3- or 4-panel comic strip. It might be extremely funny on the page, but it can become much less funny if you read it out loud, or try to act it out. I thought the first “Uncle Gus” short I wrote was hilarious on the page, but it just didn’t translate to animation the way I hoped it would.

L’IDEA: In 2003, “Big Nate” the musical debuted, with great success. Was that your idea? How involved were you in that project?

LINCOLN PEIRCE: Adventure Theater, one of the oldest and most respected children’s theaters in the country, approached us and inquired about the stage rights to Big Nate. I was initially skeptical, simply because so many things can go wrong when you put something you’ve created in someone else’s hands. I’d never collaborated on Big Nate before; I don’t have a partner or an assistant, I don’t buy jokes from free-lance gag writers. So I had to get used to the idea. But once the writers submitted their story synopsis to me, I was on board. There was a good story there. I was grateful to the writers, because they let me re-write most of the dialogue. I didn’t touch the songs, except to suggest that one song needed to be more upbeat. But it was important to me that when the characters spoke, they sounded like the characters I’ve been writing for all these years. My family and I went to the premiere last spring, and it was wonderful. They did a great job.

L’IDEA: You were a pen pal with Jeff Kinney, the author of “Diary of a Wimpy Kid,” How did that come about?

LINCOLN PEIRCE: Jeff was an undergraduate – and an aspiring cartoonist – at the University of Maryland. He read “Big Nate” in the Washington Post and enjoyed it, so he sent me what I guess you’d call fan mail. He had a lot of questions about cartooning, syndication, etc., and he sent me examples of the strip he did for his college paper. It was called “Igdoof.” He was clearly very talented, earnest, and ambitious. I wrote him back – this was before the days of email, so we really were pen pals in the old-fashioned sense – and we kept a correspondence going for a couple of years. We lost touch after he graduated, but found each other again after his first “Wimpy Kid” book was published. I read about his success, tracked him down to congratulate him, and as I mentioned in one of my earlier answers, he’s been enormously helpful to me.

L’IDEA: Are you working on any projects not involving Big Nate?

LINCOLN PEIRCE: At some point, I am definitely planning to write other books for kids that are not Big Nate-related. But there’s still one more novel to write after the one I’m working on now. That will make a total of 8 Big Nate novels, and at that point I’ll be ready to try some other things.