by LindaAnn LoSchiavo for L’Idea

My mouth was full when I met the genial food historian Andrew P. Coletti at the Italian American Museum’s “Brindiamo!” He was one of two foodies who filled the buffet table with fascinating fare, as a favor to museum founder Joseph Scelsa. His fancy dried dates (stuffed with ground walnuts, pepper, honey, and sea salt) were so scrumptious that it would encourage many hosts or hostesses to start cooking as if they were expecting Julius Caesar.

How did the invitation reach an emperor (or any VIP), since engraved greetings had not yet been invented? “For an intimate party at a wealthy Roman’s mansion, it was customary to have nine guests to represent the Nine Muses,” explained Mr. Coletti. “Slaves or servants would be sent as messengers to an individual’s residence to personally invite him.”

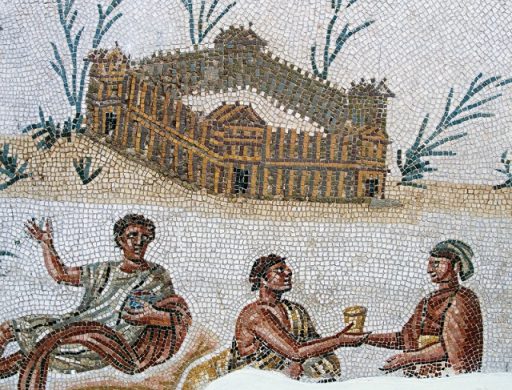

Circa 100 B.C., a ruler, a senator, or other notables would be ushered into the host’s grand entertaining area designed to accommodate nine adults. The triclinium was a three-couch room, its broad beds arranged along three walls of the home in a U-shape. Murals, mosaics, and other works of art were part of the lavish décor, displaying the household’s eminence.

Diners reclined during mealtime. They propped themselves up on the left elbow, three adults per divan, and ate with the right hand. According to Mr. Coletti, guests were expected to bring their own cloth napkin and utensil (a spoon). Before eating, diners rinsed their hands in tableside finger bowls, then used their own napkin to dry off. But the concept of buying a “hostess gift” or BYOB was light years away. “The Greeks and later Romans had strong customs of proper hospitality,” he emphasized. “Therefore, it was the host, not the guest, who was expected to provide everything; the guest’s role was to accept the meal and any other gifts with gratitude.”

“Octavi, da mihi phoenicopterus!” or “Octavius, pass the flamingo!”

Since Andrew Coletti named his web site “Pass the Flamingo,” naturally everyone has the same question: would they really consume a phoenicopterus?

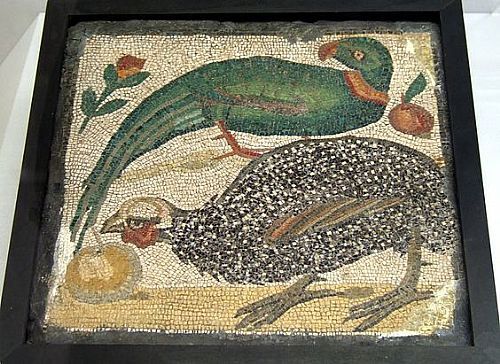

“Most definitely. Upper-class Romans liked to flaunt wealth by serving items that an average citizen could not afford such as pepper or dried spices from India and Persia, along with exotica from the far reaches of the Empire — — camels, flamingos, or ostriches,” he replied. “Stories are told about the over-the-top extravagance of Emperor Elagabalus [203 A.D.—222 A.D.], apocryphal perhaps. One rumor was that, during his short, decadent reign from 218—222, Elagabalus would serve dinner guests tables piled high with only the heads of flamingos, and sacrifice flamingos to the gods instead of chickens.”

“As a protein source, the flamingo was rare, thus expensive,” he continued. “The bird had to be imported from far-off Roman provinces in North Africa or Egypt. Since the poet Martial mentioned flamingos among the livestock on a wealthy man’s farm in Baiae (near Naples), it seems some Romans were able to raise them in Italy. This was not a common practice.” Mr. Coletti added wistfully, “I wish we knew more about the logistics of ancient flamingo farming. I assume their wings were clipped to keep them from escaping. But I wonder what sort of diet these birds were raised on.”

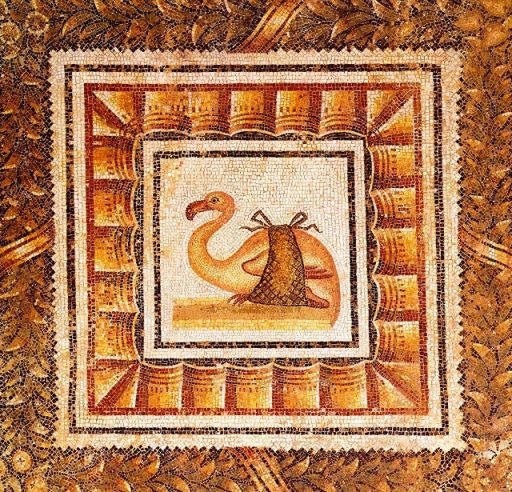

Museum-goers may have seen art depicting the ancients feasting. Mr. Coletti said, “One mosaic depicted a whole trussed-up roasted pink flamingo sitting on a platter as if alive! This image from Roman North Africa, where flamingos are native, is in Tunisia’s Bardo Museum. That sort of Roman showmanship is similar to the later Medieval custom of presenting peacocks and swans in lifelike poses at the table with their feathered hides laid over the roasted flesh.”

The ability to generate awe among visitors was part of the planning. “A flamingo or roasts, in general, would have been cooked, then presented to the guests whole — — for that “wow” factor — — then sent back to the kitchen and cut into bite-sized pieces,” he explained. “Dinner tables were not set with knives. Romans ate with a spoon or their hands.”

“Ubi est coquus?” or “Where’s the cook?”

And how was it cooked? According to Mr. Coletti, one recipe in the 5th-century Roman cookbook Apicius is for a whole roasted flamingo with a thick sauce containing cilantro, grape juice, assorted spices, and dates. Similar preparations were used for chicken and ostrich. “This was the first recipe I ever made for my ancient food blog, Pass the Flamingo,” he said, “which derived its name from that experiment. In the USA, flamingos are protected by law. So to recreate that recipe, I used a duck, figuring it would be the closest possible substitute. Based on anecdotal evidence, I surmised that real flamingos probably had a strong, fishy flavor. However, I was only able to obtain a domestic duck. Hindsight indicates a better option would have been a wild-caught fish-eating duck such as a merganser.” Warming to the subject, he elaborated, “The flamingo’s tongue and brain were delicacies. Flamingos have a particularly large, muscular tongue, and the Romans liked to eat the brains of various other animals, too. It occurred to me that this is why Elagabalus would serve only the flamingo’s head.”

“Augusti, da mihi dentiscalpia!” or “Augustus, pass the toothpicks!”

At this point in the feast, a Roman politician may have been burping. Or looking around for a toothpick. “Romans made toothpicks from the wood of the mastic tree, which is not a conifer but also has a piney smell and flavor,” he noted. “Mastic resin was also used as a flavoring in spiced wine.” And this bronze toothpick, discovered in ancient Rome, was shown in a dental journal.

During that era, what beverages were served to the thirsty? Coletti explained that, aside from various kinds of wine — — which was almost always watered down for serving, a custom also practiced by the Greeks — — and mulsum, which was spiced wine sweetened with honey, Romans typically drank a non-alcoholic beverage called posca made of watered-down vinegar, as well as hydrogarum, a watered-down fish sauce. They shunned beer, which was associated with the natives of Germany, Egypt, and the Middle East, all enemies of the Romans.

In the ages before refrigeration, what was the most common method of food storage? “Romans preserved their food by sun-drying, pickling, salting, and preserving in honey,” he pointed out. “They made dried sausages (farcimen) very similar to those still eaten in Italy and France. Ice and snow were considered luxury items for cooling beverages and food. Wealthy citizens imported snow from mountaintops and kept it from melting (temporarily) in underground cellars.”

Perhaps Italian readers are wondering when we will mention pummarola, the fruity Neapolitan tomato sauce. It may come as a surprise that the tomato started life as a tiny berry; botanists classified it as a fruit. When did the tomato grow up and get into Mediterranean recipes? “Tomatoes are originally from Mexico and were first used by the Aztecs,” Mr. Coletti said. “The name comes from the Nahuatl (i.e., the Aztec language) word tomatl. Thus this berry did not reach Europe until the 16th century, after the Spanish conquest of Mexico.” He continued, “Tomatoes were first grown in Europe as an ornamental and are scarcely mentioned and even treated as a curiosity in the major Renaissance Italian cookbook, Bartolomeo Scappi’s Opera (1570). Scappi’s book contains the first recipe for a modern pizza, but it was a white pizza! However, by the 17th century, the tomato was well-entrenched in Spanish and Italian cuisine.”

“Quid de solani mortiferi?” or “What about the deadly nightshade?”

Throughout history, suspicion was attached to anything related to atropa belladonna, even the harmless edibles in the deadly nightshade family. Did the ancient Romans avoid deadly nightshade vegetables? “They knew of deadly nightshade itself,” he affirmed. “In small doses, it was used to relieve menstrual cramps and other ailments. In larger doses, it was a potent poison. But the harmless veggies related to the plant were unknown to the Romans, for instance, tomatoes are Mexican, potatoes are Peruvian, and eggplants are Asian and were introduced to Europe in the Middle Ages by the Arabs.”

It is strange that the ancient Romans did not have access to many ingredients essential to today’s Italian recipes, such as the tomato and eggplant. At this, Mr. Coletti laughed. “Imagine a culinary landscape without any of the following: corn, tomato, eggplant, potato, chili pepper, turkey, coffee, tea, citrus fruits, rice, and pasta.” He added, “That doesn’t mean Roman cuisine was limited; for every plant or animal the Romans were unaware of — — because it was from a far-flung region — — they enjoyed items we no longer eat such as medlar-fruit or dormouse.”

What is the flavor profile of ancient Roman cuisine? “Romans appreciated bitterness as a flavor much more than most cuisines today. A lot of favored Roman herbs like rue are very bitter. They used salty, savory fermented fish sauce (garum) as a base for almost every dish. The pungent, oniony spice silphium was a favorite ingredient, so much so that the plant which produced it was over-farmed into extinction. It is similar and related to asafetida, which is mostly seen today in the cuisines of India. The Romans would consider asafetida a lower-quality substitute for silphium. Chili peppers are from Mexico so the Romans did not have anything spicier than black pepper,” he explained. “Moreover, since their only sources of sugar were fruit and honey, Roman food is relatively low in sugar. Archaeological remains showed that Romans had good teeth. Generally speaking, Romans ate a lot of vegetables and seafood; meat was reserved for special occasions — — except for the very wealthy.”

What was the most surprising detail Mr. Coletti discovered about ancient Roman cuisine? “Aside from the flamingos being raised on farms, I was intrigued that Varro, who was writing in the 2nd and 1st centuries BC, provided instructions for creating an artificially moist environment for edible land snails using a pipe that produces mist,” he recollected. “I was so impressed by how modern that sounds.”

“Plinii, da mihi liber coquinaria!” or “Pliny, pass the cookbook!”

How do Roman cookbooks differ from modern ones? According to Mr. Coletti, since these books were written for professional chefs, the Roman cookbook Apicius has few measurements and no precise temperatures nor times. For example, a recipe will say “season well,” implying that the chef has a fully-stocked Roman pantry and knows what that means. He added, “Apicius is organized along the lines of a modern cookbook, however, with different sections for different kinds of food, and additional sections with tips and tricks for saving money or time in the kitchen. Some of these suggestions are a bit unscrupulous, for instance, how to flavor cheap olive oil with herbs to make it taste like a higher-quality product, or how to mask the taste of ingredients that have gone bad.”

“Ad ovosque ad mala” or “From beginning to end”

Did Roman cuisine directly influence other cuisines? According to Mr. Coletti, the Medieval Arabs, who preserved and studied many Western Classical texts, also carried over quite a lot of Roman culinary traditions, including the heavily spiced sweet/bitter sauces served over chicken and fish. Then, during the Middle Ages, Western Europeans attempted to distance themselves from “decadent” pagan Roman cuisine, while in the Byzantine (Eastern Roman) Empire, folks tried to emulate the Romans, basing their cuisine around a salty, fermented condiment called murri, which aside from being made of grain instead of fish was very similar to Roman garum. However, the dining patterns of the Romans are still followed today.

He continued, “Modern Mediterraneans eat a light breakfast and lunch and a big dinner just like the Romans. And the ancient Romans were the first to serve a three-course meal of salad or appetizer, entree and sweet dessert. The Roman expression ad ovosque ad mala meant from beginning to end (literally, from eggs to apples). This is because Roman meals often began with something to nibble on like hardboiled eggs, and then concluded with something sweet like apples. Our expression ‘from soup to nuts’ is similar.” He added, “The Latin word for dinner, cena, is spelled the same in modern Italian, although the Romans pronounced it with a hard C instead of a CH.”

“Caligula, vomitorii indica mihi!” or “Tell me about the vomitorium, Caligula!”

Let’s conclude by clearing up a popular misconception. Mr. Coletti wished to clarify that there’s a legend that Roman diners would force themselves to throw up at a place called “the vomitorium.” Except it’s not true. Vomitorium was the name for the exit passageway from a public building.

For further reading, he highly recommends “Feast of Sorro: A Novel of Ancient Rome” by Crystal King, focused on the Roman gourmand and cookbook author Apicius. The famed epicure Marcus Gavius Apicius flourished during the reign of Tiberius, early in the first century AD.

A graduate of Bard College and Bank Street College of Education, Andrew Coletti is available for food lectures and consultation for private events. The Connecticut native has given food and history talks at the Brooklyn Brainery and Caveat in Manhattan’s Lower East Side. His next event will be focused on the cuisine of Ancient Greece. Upcoming food events appear on his web site: www.PassTheFlamingo.com.

He has also been writing fantasy fiction and his novella “The Knife’s Daughter” will be released by Pink Narcissus Press on July 10, 2018.